Big Sky Infinity Review

Procedural generation may be little more than a buzz word around most design circles right now, but for game design, it’s old hat. Roguelikes and RPGs have utilized procedural generation as a means of bypassing memory limitations since the medium’s formative years. In that sense, 2009’s Big Sky was drawing upon a long and storied lineage when it brought randomly-generated content to the shoot ‘em up genre. Big Sky Infinity, the PSN’s enhanced edition release, now brings that formula to Sony’s console and handheld.

Traditional shoot ’em up games pit the player against a set of static levels, to be practiced until their patterns are set to memory. Big Sky Infinity eschews that convention in favor of one-off runs, populated by a dynamic assortment of enemies and obstacles. Here, the difficulty is ramped up at a rate determined by the player’s proficiency, and play continues as long as one can survive. It’s an innovative and wholly fitting application of procedural generation. Unfortunately, two-person developer Boss Baddie seems to lack the clout necessary to hit the concept’s full potential, and an assortment of missteps serve to knock Big Sky Infinity a bit further down the ranks of indie offerings.

The scenario that you’re tasked with is a familiar one: aliens are attacking [insert your home planet here] and there’s nothing standing in their way save your little ship and a whole lot of space. Big Sky Infinity is a shooter of the twin stick variety, allowing full range of fire within its side-scrolling game space. Like the celebrated twin stick titles by developers like Housemarque, Big Sky Infinity comports itself quite admirably on Playstation-brand analogs. Shooting feels responsive, your ship seems formidable, and your attacks ring out with satisfying audiovisual effects. Within seconds, you’ll be flitting about the screen, mowing down neon-colored foes to the beat of the soundtrack’s potent mix of dance and electronica.

In case you couldn’t tell from their name, Boss Baddie sport a sort of glib nostalgia towards gaming’s history and nerd culture at large, and it’s on display in nearly every facet of Big Sky Infinity. Retro nods abound, from the pixelated high score fonts, to the heart-shaped “extra life” icons, and the bevy of other such gaming tropes that are invoked with regularity. There’s a charming, decidedly British irreverence to the game’s humor, too. It’s exemplified in Big Sky Infinity’s enemy descriptors, which imply that the basic enemy might not even be evil and riff on the fact that the solution to nearly every problem in the game is to shoot it with more lasers. That charm, however, doesn’t carry through to Big Sky Infinity’s in-game comic announcer, a swing-and-a-miss inclusion who sounds like he was recorded on a shoddy microphone. That’s a shame, because it represents the sole avenue through which Boss Baddie’s humor permeates into gameplay.

Thankfully, the played experience manages well enough on its own, by and large. Your spacecraft controls exactly as you’d hope, making it easy to zip around the screen while firing towards whichever direction stuff needs zapping in. For your troubles, you earn starbits, delicate little collectibles which enemies drop in handfuls, and which fuel Big Sky Infinity’s upgrade system (more on that later). In addition to your run-of-the-mill lasers, you’re also periodically blessed with a suped-up version that devastates anything it brushes over, and a drill move that acts as a counterpoint to your standard weapon.

Drilling is a curious addition. It allows your ship to penetrate screen-wide planets that intermittently appear, as well as the shells of a couple of the bosses. In practicality, though, it’s not a very interesting feature. You’re typically given ample warning when planets approach, so the matter of pressing the drill button becomes so trivial as to seem wholly unnecessary. One might expect that the drill might serve as a means of defeating enemies, thereby establishing the sort of dual-technique system found in genre standouts like Einhander or Ikaruga. But that’s a feature that’s limited to your charge-up “spin” drill attack, a limited-use weapon that’s effective against most enemies. Now, you might be wondering why I consider the two to be separate entities – if the drill can indeed be charged up to defeat baddies, then isn’t my earlier point about its lack of utility invalid? But strangely, the charge up move doesn’t work like the regular drill move does. Hit a planet, asteroid, or other such impassable object while using the spin attack, and you’ll be just as dead as if you flew headlong into it with your Prius. It’s a counter-intuitive design choice, and one of my largest sources of death. It’s tragically easy to crash into a tiny, one-hit-kill asteroid when you’re flitting about the screen, trying to destroy enemies with your drill attack. To compound the problem, there’s no timer cue on the spin move, so it often wears out just as you move to plough through an enemy.

While there’s really only one “level” in the game, the procedural generation does manage to keep the experience fresh by constantly switching up your encounters on the fly, so that no two runs are alike. While I do think that randomness largely serves the game well, know that it can occasionally frustrate. In fitting arcade fashion, Big Sky Infinity’s end game is the all-important high score, so it can be grating when the game’s algorithms don’t serve you up the right enemies or bonuses to top off your performance on a good run. Thankfully, if any one attempt gets you down, there’s a solid offering of alternate game modes available that pepper in challenges like arcade modes, no-weapons runs, and boss rushes. Classic, the de facto “main” mode, lets you improve your ship after each run, using collected starbits towards upgrades to your shields and an arsenal of indirect lasers. They’re a welcome addition, and after some work you’ll gradually notice the subtle effects that they have on your performance. Upgrades cost an exponentially increasing number of starbits as they improve along their sliders, so it looks to take quite a bit of work to max out your craft.

But surprisingly, upgrade systems and performance tracking don’t stop Big Sky Infinity from lacking a tangible sense of progression or accomplishment. Since you’re essentially limited to one extended level, the sense of familiarity with the environment grows until it becomes a bit dull. And though every run is different by some measure, on the grander scale the sameness of the general experience begins to wear you down. It’s telling, for example, that the graphs representing each of your attempts are indistinguishable from game to game. Invariably, mine always end up looking like a gently sloped line that peaks suddenly, then ends. That’s not to say that Big Sky Infinity needs levels, but some fiddling with the presentation could really have helped to engender feelings of accomplishment. Terry Cavanaugh’s Super Hexagon, for example, achieved this by going out of its way to highlight the seconds that players survived, as well as calling out levels of progression as they advanced. By contrast, Big Sky Infinity feels inscrutable. It’s difficult to judge exactly how the difficulty is scaling to your abilities, and the de facto signifiers of performance, your score and multiplier, are tucked into a corner where you’ll never look when the action starts to really heat up.

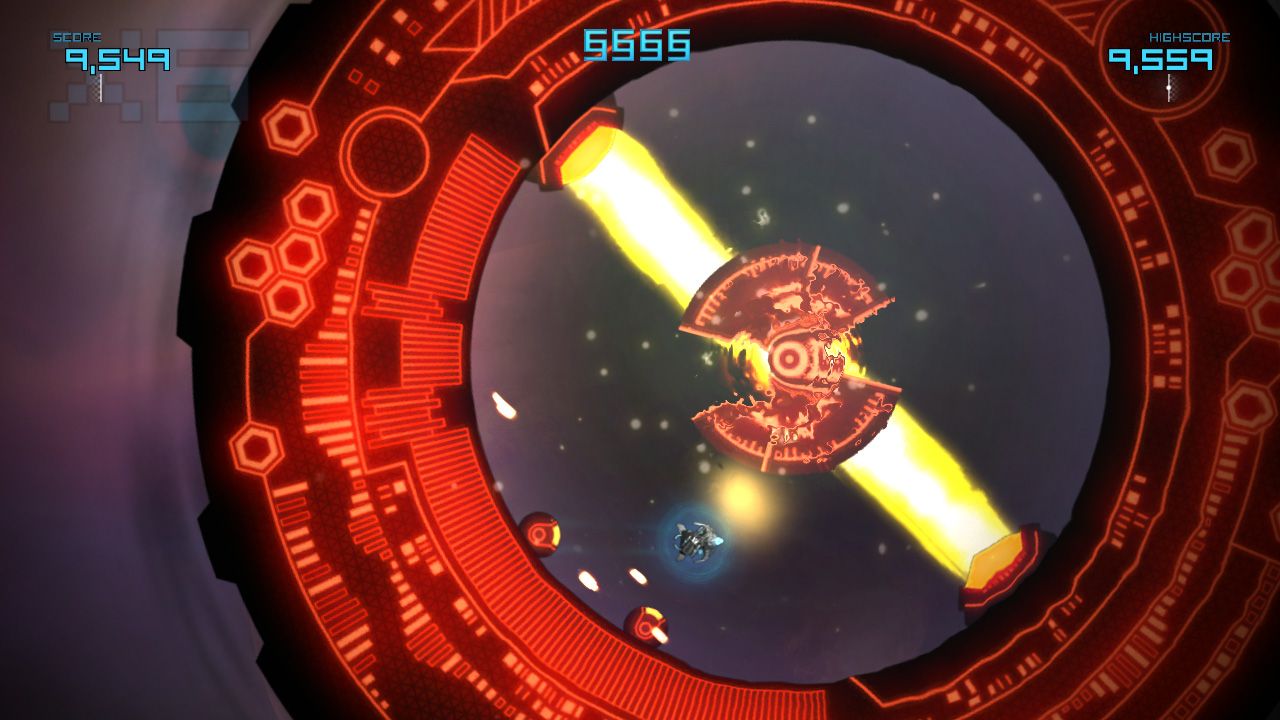

I don’t want to undersell that last part – Big Sky Infinity is prone to erratic spikes in difficulty, and when they hit, they hit hard. In an otherwise untaxing run, you might abruptly find yourself beset by a swarm of enemies, as asteroids hurl at you, lasers fire from off-screen, and the screen de-saturates to an indistinct wash of black. Big Sky Infinity isn’t so much a “bullet hell” game as it is a “neon stuff hell” one. You’ll be hard-pressed to make out your own ship in the spectacle, let alone where the hazards are. The backgrounds contribute to the problem, too. While the rainbow nebulas and gas clouds are pleasing to the eye, too often they blend with the lasers and enemies, making it all the more difficult to react properly.

It all adds up to mean one thing: death in Big Sky Infinity comes suddenly and without warning. Nine times out of ten, you won’t actually know what killed you; whether your craft explodes in the midst of a laser light show of enemy fire, or in the greyscale darkness of a black hole, you likely won’t see your end coming. And that’s after you’ve gone through the ringer that is Big Sky Infinity’s trial-and-error acclimation period. The game’s first few hours were marked by one recurring utterance: “Huh….so I guess that can kill me?” In early sessions, I suffered a variety of avoidable deaths by: flying into deadly gas clouds (that look exactly like harmless gas clouds), shooting at invincible enemies, shooting at enemies that harm you when shot, trying to drill through features that can’t be drilled through, and trying to spin through enemies that can’t be killed via spin. The Library’s inclusion is clearly intended to mitigate this feeling-out process, but it errs more on the side of humor than helpfulness, and tragically, stops showing images of its entries right at the point where you start really needing them. A decision motivated by the desire to reserve some secrets and surprises, no doubt.

Big Sky Infinity plays some such hands close to the vest, so that there are a few new experiences waiting down the line on a successful run. I’ll happily grant that there’s fun in the once-in-a-blue-moon appearances. Yet the more significant result is that after all this playing, there are still many things that insta-kill me in Big Sky Infinity, and I still don’t know what they are or how they do it. I’m stuck trying to recall the circumstances of my death, in order to pair them up to a vague descriptor in the library. “Was it the glowy orb thing that did me in? Or maybe the black dot?” Who can recognize or learn from a challenge that you rarely encounter, that comes only when you’re distracted and overwhelmed? Too often, I find myself putting down, “Cause of death: Artificial Difficulty” – that cardinal sin of game design.