Ambiguous Exposition: Mass Effect 3 and Journey

Posted by

matski53

on

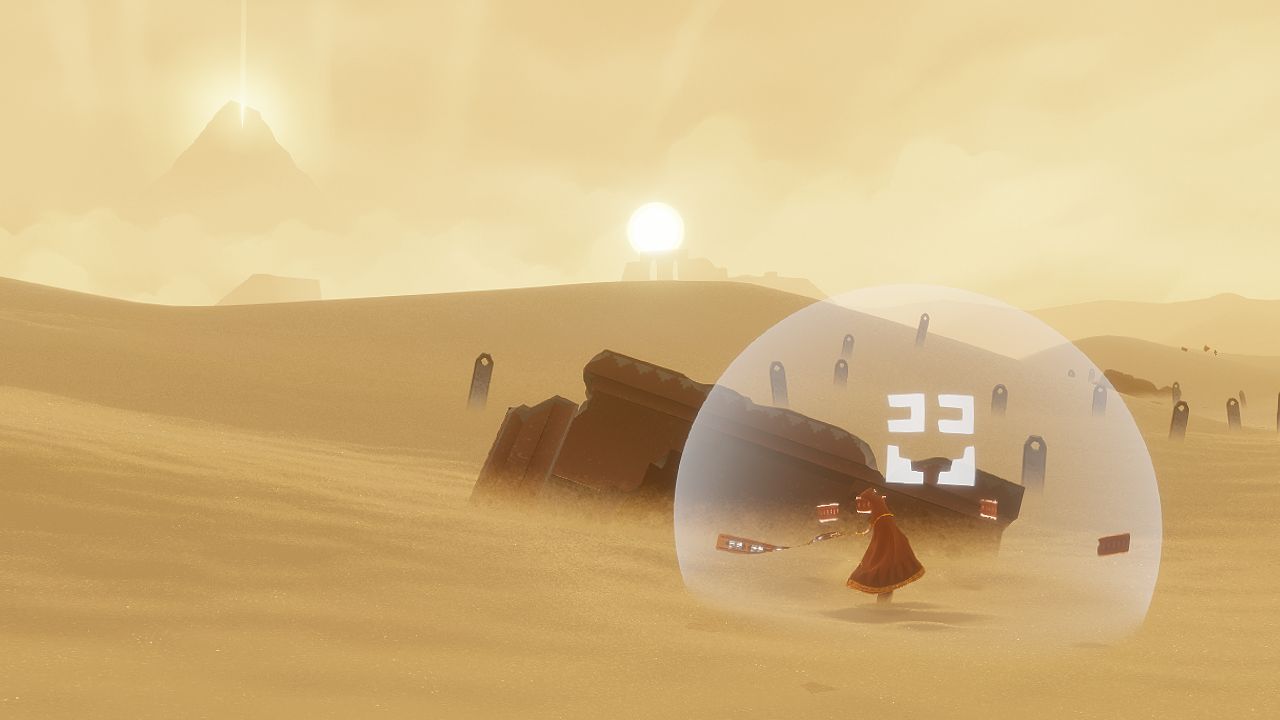

“Oh narrative, narrative, wherefore art thou narrative?” pondered a wandering, introspective, maroon cloth shrouded silhouette as it traversed the lonely dunes of a vast desert. “Over here, pretentious!” replied the ballsy, bull-headed, N7 armour suited space marine: ‘Sheeplover’ Shepard (my personal commander’s name). And so begins the fan fiction conversation between the protagonists of Thatgamecompany’s Journey and Bioware’s Mass Effect 3 within my head…

For two titles released within a week of each other, they couldn’t have more opposite approaches towards weaving the delicate tapestry that is an interactive narrative. Both are action adventure titles, taking mechanics, structures and ideas from others and moulding them into their own experience. Journey integrates light platforming with visual cues to aid progression and Mass Effect 3 employs a science-fiction twist on Gears of War-style cover shooting with an abundance of dialogue. In addition, both send a central hero on a monumental task of life threatening danger and bravery, but the similarities end there when you begin to consider their diametrically opposed approaches to storytelling.

One is a hinted tale awash with ambiguity and personal interpretation, and the other a well-defined fiction of choice and consequence detailed by reams of exposition. They are both titles at the forefront of videogame narrative design, but in what dimensions are they so different? Does each succeed where the other fails? Many would undoubtedly go as far as to claim that Journey doesn’t truly have a narrative beyond ‘Silent traveler climbs big mountain to reach shiny thing at top’, which is perhaps a valid point should you examine it solely at face value. However there are many others (including myself) who would vehemently oppose such an opinion.

Throughout its length Journey is peppered with vagueness. It is entirely wordless, the characters are expressionless puppets and its MacGuffin is an ever-present mystery looming in the distance. This is evident even within its more common narrative devices. The cutscenes depict the near past, present, and future of your adventure, like the ghosts of “A Christmas Carol” all rolled into one, while its lands are littered with 8-bit stylized cave paintings of events, though nothing is ever fully explained. Progression in Journey is never far away from a metaphor, a mythical monument, or a suggestive artifact.

Where it succeeds is in balancing this ambiguity on the teetering edge of bewilderment. Its mechanics and structure raise such a myriad of questions, that by answering them with suggestions rather than definitives, it invites your imagination to run wild. We know the goal is to reach the gleaming beam of light at the summit of this mountain, but for what purpose? We learn how to invigorate the floating cloth creatures with our voice, but what are they and why do they help us? There are so many who’s, what’s, where’s, and why’s left after Journey finishes that you cannot help but inquisitively ponder.

In complete contrast, Shepard’s world is a veritable smorgasbord of exposition. You need only access his journal to find yourself buried in the avalanche of details contained on each humanoid, bipedal race of galactic stereotyping, vast numbers of planets each with their own ecological and environmental backstory, the numerous ships, weapons, and the implausible yet convenient technologies his universe is stitched from.

Mass Effect 3 travels the common space opera route, presenting a glut of detail that dusts away every obfuscating speckle of ambiguity with pseudo-scientific facts and backstory. Even relatively minor species that are rarely implicated in the story, such as the Hanar or Elcor, are given home worlds and an evolutionary explanation detailed around their native habitats and political motivations. If Shepard were to land on the alien planet of Thatgamecompany, you can’t help but imagine that his codex would be brimming with detail on the variety of local fauna and the indigenous species’ evolutionary reason for a lack of arms. It is a completionist’s paradise. A world of information that is easy to get absorbed in, should you enjoy such detail, and quite the opposite of Journey’s enigmatic presence.

Where the Mass Effect franchise attempts to draw an emotional response from players is in the practically Newtonian laws of choice and resulting consequence. It eschews the medium’s commonly linear narrative structure (to a limited extent) and allows you to make meaningful decisions that affect the course of your story. In Mass Effect 1 for example, you are given the choice of saving a Krogan squad mate or killing him when your desires clash. In Mass Effect 2 you have the choice to carry out specific tasks for each of your teammates, determining their eventual fate in the concluding chapter. And in Mass Effect 3 numerous decisions you make have consequences that can see entire species wiped out altogether.

It is possible therefore that my experience of Mass Effect 3 was vastly different from yours. Where you might have played a paragon, saving everyone you could, I may have indulged a bloodlust for murder with renegade choices. This may sound like a standard Fable style good and evil ethic-o-meter, but Bioware masterfully utilizes this technique to build attachments to the characters of Mass Effect through the knowledge that, whether I chose to kill Wrex or not, will have lasting repercussions within the universe and throughout the whole series of games. It is because of this continuity that decisions become all the more salient and unusually meaningful for a videogame.

I killed him. Two games later, I missed him.

Journey’s handling of choice is, well, non-existent considering that there are effectively none to be made throughout the adventure. It is a point A to point B rollercoaster of set pieces much like a Call of Duty campaign, with multiple playthroughs offering up what is essentially the same experience.

Yet within this constraint Thatgamecompany are able to exhibit a cinematic sense of control over what emotion any moment in Journey will provoke – going as far as ripping control away from your thumbs at times, to be concentrated on a particularly beautiful angle. This design choice makes a lot of sense when you consider the fact that Jenova Chen and his team begin a development process by deciding on the emotions they want to portray before anyone even suggests a mechanic.

The one area in Journey that Thatgamecompany doesn’t take complete control over is the co-operative multiplayer. Its portrayal of companionship may be an extremely limited affair with nothing but your personal symbol and sounds to communicate. Yet the reduction of interaction to such a simplistic form removes so many complicating barriers and boundaries. You may not know the detailed history of your companion as you would of Wrex in Mass Effect, but I found that most everyone I came across was willing to share this Journey with me, evoking the childlike joy of friendship free of preconceptions.

The image of 2 wanderers in a lonely desert is a striking one to be sure, and if a picture can paint a thousand words, then Journey’s aesthetic paints a thousand pictures. Drawn with a slightly ethereal and otherworldly presence, Journey is constructed from hazy yet simplistic cell shading that adds to the overall ambiguity of its structure and narrative design. Mass Effect 3 on the other hand is an unflinchingly stark visual depiction of a universe at war. All cold metallic space stations, colorfully incandescent nebula’s, and lens flare saturated destroyed cityscapes. Its visuals are as serious as its sombre plot.

Each game’s visual depiction serves to aid their method of storytelling, just as the protagonists of each adventure do. Journey’s wanderer may be expressionless, but it is essentially a puppet, a cypher like Link or Gordon Freeman through which the player can experience the freezing blizzards of a harsh mountain, or the gleeful joy of sand surfing. Commander Shepard, on the other hand, is very much your own personalized avatar. Make it male, make it female, make it look like you, choose your own backstory, punch the journalist, don’t punch the journalist. It truly is up to you.

“This war will affect all of us! The fate of every organic species in the galaxy depends upon us putting aside out differences, pulling together as a team, and fighting the Reapers. Are you with me?”

Mass Effect 3 is a Pokedex of detail, explaining every last point of intrigue, yet granting a level of personalization to its narrative that fosters investment. Whereas, like that monolithic slab in the opening scene of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Journey is a grand rigid structure of intrigue that has the power to illicit wonderful and provocative thoughts and ideas in the minds of those willing to dream along with its ambiguity. So where one is suggestive, the other is explanative. Where one starves you of detail and invites you to imagine, the other aims to saturate your curiosity with information and exposition. Where one strives towards personalization, the other presents a pre-designed experience, consistently engineering images that tug on your emotional heartstrings.

I would not be so arrogant as to suggest that one style of storytelling is better than the other. What you are emotionally affected by is a hugely personal and subjective, dependent upon many extrinsic and intrinsic factors. All I know is that one of these games truly moved me and the other simply gave me the freedom to move it, which speaks volumes of the narrative potential within gaming today.