Frostpunk 2 Review

Battling the elements, inside and out

There was a period of time recently in the gaming sphere where survival elements peaked in popularity. And aside from the avalanche of janky, early-access third-person action games, the element of danger creeped into other genres as well. Titles such as This War of Mine, State of Decay, The Banner Saga, I Am Alive, and more, had players foraging for resources and shelter while making harsh narrative choices. One of the more recent games to integrate the challenging elements of survival was Frostpunk, which combined dramatic storytelling and difficult decisions with a city building element. This combination proved to be unique and found success, so a sequel followed. With the recently released Frostpunk 2, things have definitely changed.

The sequel takes place in an alternate version of history, during the early 1900s and about 30 years after the events of the first game – when an apocalyptic blizzard destroyed much of life on Earth and turned it into a mostly frozen hellscape. In Frostpunk, survivors banded together under the command of the player known as the Captain, finding a volcanic source of heat and building a city of New London around it. Many difficult decisions had to be made when dealing with extremely scarce resources for both food and construction, as well as managing the ever-dwindling heat sources and workers across the city. The sequel kicks off with what appears to be the death of that original Captain, and you rise as a new nominee for his position. Across the somewhat brief narrative campaign, you will have to guide the people of this city and make decisions, and hopefully establish yourself as the new leader that will keep things humming along.

The campaign begins with a tutorial that provides a quick intro to the new gameplay systems – and things start quite differently. Rather than being a direct sequel, Frostpunk 2 really changes up the mechanics and turns into more of a Civ or strategy game, rather than a city builder. From an isometric but freely rotating camera, you will observe the land around a broken down engine, and start clearing the snowpack by clicking on tiles with the tool selected. This ties up some workers for a brief time, which can be sped up, or paused. With the snow cleared, those tiles become viable for placing districts, and you can choose to designate them for housing, extraction, or industrial manufacturing. The districts have a minimum amount of tiles that they need, so between that and the snow pack clearing, there's a bit of busywork that doesn't seem to pay off a whole lot in terms of gameplay fun.

With the districts constructed, they will begin to perform their function – be that resource extraction or housing your workers and providing shelter. Resources remain critical and are finite, and it's possible during the tutorial to expand and construct in the wrong order, while you're learning which resources are needed for what function, and leave yourself stranded and unable to complete the mission, as too many people perish and not enough materials are gathered in time. The game warns of this with a message, that the harsh conditions may need many attempts to get through – but that's really not the case. Once you've figured out the materials and building patterns, you're set for the rest of the game. It may take a couple of restarts, but after that it never becomes a factor.

Following the tutorial, players arrive at New London, and you get busy with clicking to clear the land around the city, and start building new districts to meet housing demand, get resources flowing, and prepare for incoming temperature dips. This gameplay loop continues for much of the game, although after you've cleared your way to the natural resource deposits on the map, there's less reason to keep expanding. Districts can also be expanded once, and that allows you to place an additional building, such as those that provide increased production, additional housing, or reduces crime and disorder.

While you'll be doing a lot of district management and construction, the interface is not exactly great. The menu is laid out across the bottom of the screen, with small icons grouped too closely, and it pops up as a horizontal menu that has the various options for districts and buildings. It's a bit awkward to navigate, not helped by the fact that the new options eventually make you scroll sideways through that selection. It's often easy to miss-click, and it can be confusing to see where you can place expansion buildings. It also definitely doesn’t help that the entire UI has a white tint to it – which is not exactly a good contrast with the endless snow of the game's world. The game was notably delayed from its earlier launch window to address the UI and other issues, but clearly more work was needed here.

Managing the tiles around the city makes up the bulk of the gameplay, which is a big departure from the first Frostpunk. No longer are you concerned with the plight of individual workers, nor can you really even zoom in far enough to see them; the city and districts feature lots of abstract lights to illustrate movement and signs of life. The people become just another resource – workers to operate the factories, and ensuring they stay fed and warm. When cold snaps roll through and you get messages that hundreds have perished – you don't really care, as they are just a number and as long as the economy is humming along, those lost will be replaced soon enough with new births and outsiders. As the city grows to 5k, 10k, and more, players pass laws to introduce mandatory schooling or marriages (which shockingly has no downsides), allow workers to use robotic limbs, or force them to work double shifts at factories, you don't really feel the impact it has on the people as the original game was able to convey; now all you care about are the stats. This shift from micromanagement to macromanagement brings a new approach, and leaves a lot of what made the original Frostpunk unique behind. It's not inherently bad design in itself – but it's a big change, which not all returning fans may appreciate.

The cold weather and material management necessary for survival do remain core elements though. Raw materials will flow in, and the UI clearly represents if you're currently gathering enough to satisfy the needs of the economy, with the rest going to a stockpile for the darker days. There are four materials to keep an eye on, and fuel is important to keep the lights on and the heat going. While micromanaging heat was one of the key unique elements of the original, now that the scope has been expanded beyond the city, it's more like just another resource. You can place some special buildings to create more heat, as well as districts next to each other for bonuses, but generally there's no need to pay attention to this element anymore. Running short on something can create trouble, such as crime and civil unrest, make people fall ill, and so on. Still, even as you run out of heat and the food stockpiles run out, you can weather the storm without too much damage, at least on the starting difficulty. The game offers a few levels of challenge, and they can even be further customized, so you can play with harsh economy difficulty but easy people management.

Some of those potential issues can be addressed with new buildings such as hospitals and guard towers that can be constructed in an expanded district. There is a meter at the bottom of the screen that indicates the level of tensions within the city – but it only really becomes a factor in the free-form games rather than during the story campaign. The campaign is split into a few chapters, each presenting its own set of tasks and events, and there are scripted elements that force certain gameplay conditions, so it often feels a bit artificial. What could have been improved are the inexact descriptions of the social elements – the game uses phrases like "tension greatly decreased", or "worker happiness slightly increased", or "production slightly decreased", without using numbers. This makes it challenging to get a good understanding of your current situation and how much impact a law or a new building will have.

To get new buildings, players will have to dive into the research trees. This menu is again somewhat confusingly laid out and takes some getting used to. The research is split into multiple categories, and allows you to unlock new laws to pass and new structures to build. Each research area often has multiple options, from the four factions in the city – each may want a different approach to things. Some may want a factory that produces more at the expense of worker happiness, while another faction wants a factory that is safer but less efficient. Players are free to research either or both, depending on how much time and materials you have. Because there is so much to research, you may end up with buildings that you don't really need, because by the time you get around to constructing it, the raw material may have actually already run out and the district is shutdown anyway.

Similarly, all laws can be researched to be available for nomination – there are no systems to lock you out of options. While this makes the research system flexible, it also makes it feel a bit meaningless, like you are never locked-in to anything and so it doesn't really matter. You can construct and pass laws from any of the so-called competing ideologies, with no repercussions for changing your mind or even constantly flip-flopping. As mentioned, there's not much humanity in it anymore, just stat manipulation, and being able to change back and forth anytime between political extremes just further emphasizes that. In both law passing and research, the game should have had better indicators that they are available for new actions – perhaps by forcing a pause on time, like it does for some narrative events that don't even matter that much and have no user input.

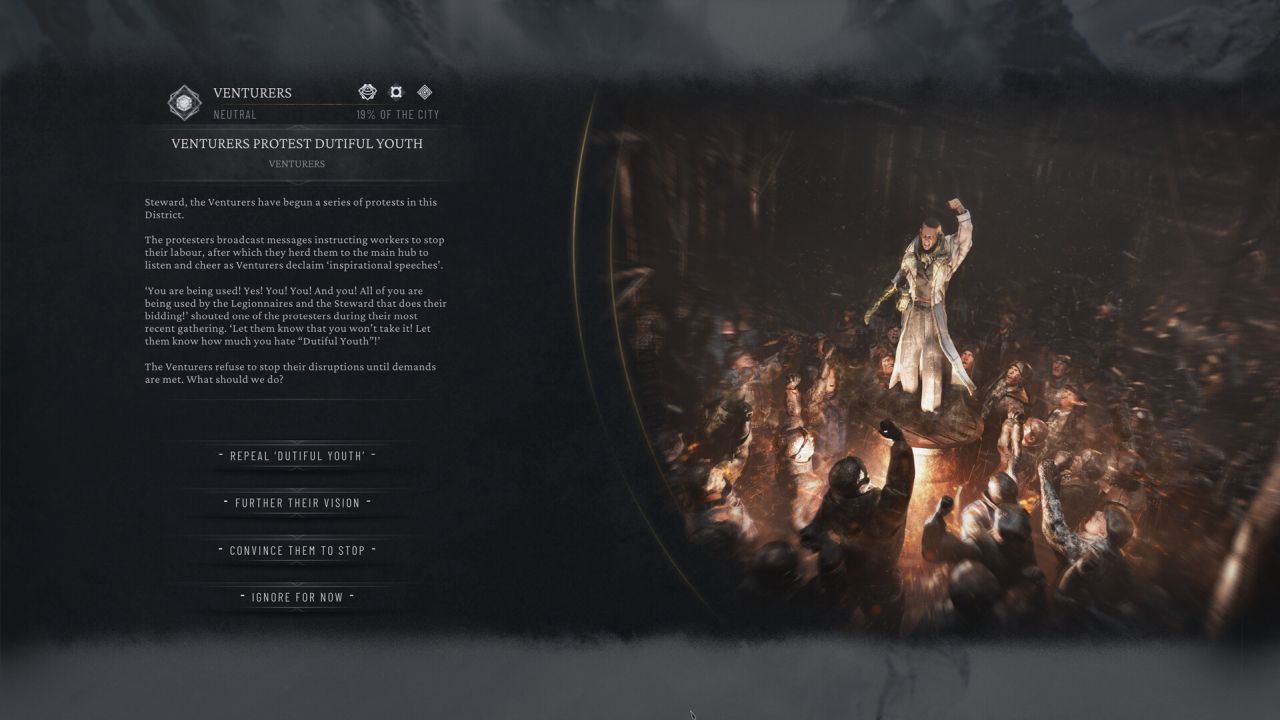

Passing laws and interacting with the factions in the city is one of the new elements in Frostpunk 2, which somewhat keeps the spirit of narrative drama and caring about your people. Through the Council Hall, you will be able to propose new laws, such as recycling heat and sending kids to factories early. In order for the law to pass at a council session, enough members have to vote in favor. The members consist of four factions in the city with different views, but the majority will be undecided most of the time, so they need to be convinced. To get them to vote how you want, promises must be made. You can promise the faction that you will pass another law they want in the future, or just research a new law or building, without even constructing it. You can even give up your chance to propose a new law at the next session, and let a faction push their agenda – but it doesn't matter, because it will fail the vote anyway, since the factions do not cooperate or manipulate like you do. So while it's an interesting and intriguing political design, the manipulation turns out to be quite easy and thus becomes a bit trivial to get the society to run how you want.

You will occasionally interact with the factions outside of the council, such as during narrative moments where they suggest a change that may change the effectiveness of an existing law. Here again though, the verbiage uses "less / more effective", which isn’t specific enough to feel the impact. The level of happiness of each faction is seen at the bottom of the screen, and it can be affected by simply offering them some bribes in the form of additional funding. With enough cooperation, you may unlock special functions of a faction, such as asking them for extra guards during unrest. Factions that are particularly happy or upset with you may stage strikes in the districts, which boosts or reduces their production – and guards can be dispatched to protect either people or property.

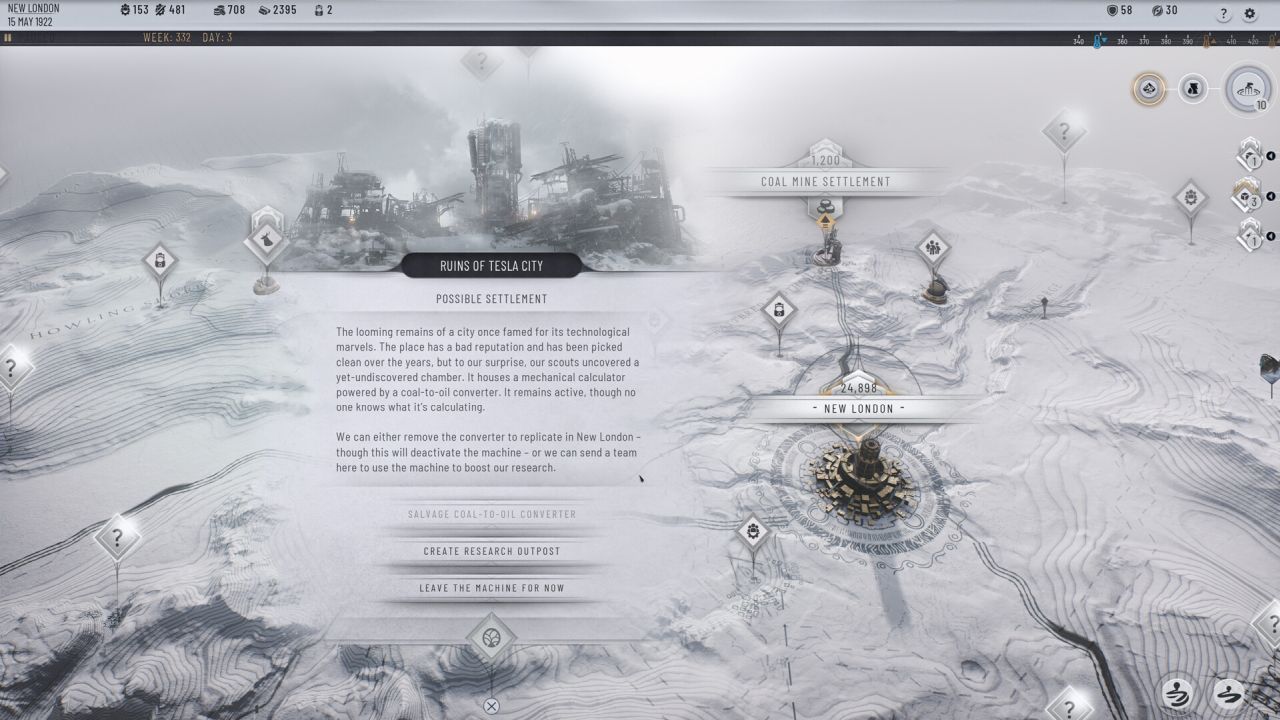

As the land is harsh and resources are finite, you will quickly need to expand beyond the immediate surrounding area of the city to find new ways to sustain the economy. After constructing an exploration facility, you will be able to zoom out into the greater Frostland, which presents a meta-game of exploring the nearby region, section by section. This takes time and explorers, but the rewards include new one-time or longer lasting resource nodes. You'll also eventually be able to setup colonies (just a menu), build roads and even entire new outposts (narrative-controlled), where you get to do more of the manual clearing of the map and setting up districts and managing the heat and resources. From these mini-outposts, you will be able to manually setup resource transfers, so that they can be sustained as well as support New London's needs. The exploration element is a welcome one, since not much new or interesting happens in New London after it's established - you're constantly just looking at the numbers, and messing around with resources. However, the UI and camera again could have been improved here, as clicking on new areas and moving around feels rather unresponsive.

The story campaign takes about 8 hours, depending on how well you adapt to challenges and how fast you wish to expand and complete the specific tasks for each chapter. Because there are scripted events that happen, it's important to just push through and not get stuck endlessly amassing resources that make you feel more prepared. The final two chapters can go by rather quickly, if you've already laid the groundwork for what is about to happen, and the story is really not very engaging. After the campaign, as most management games, Frostpunk 2 offers a more freestyle Utopia building mode. Players get to try and survive on a series of new maps and with new factions in the city, with differing but familiar splits across ideological lines.

The game retains the frosty art style of the original, with some cool bleeding effects of the menu icons and shifts in contrast from white to black when things are going sideways. It's a cool art style (pun intended), this time supplemented with a few brief pre-rendered 3D cutscenes. The audio design is also fitting, with a good selection of background music to suit the survival theme. Performance is mostly decent, though we experienced some serious slowdowns during certain parts of the campaign when too many elements (scripted) were happening in the city.

Frostpunk 2 is an interesting sequel. Not necessarily because of what it contains, but rather how it fits in the now-franchise. With no intimate management of people, the game lacks an intense level of atmosphere and dread of its predecessor. It feels more like playing a well-crafted mod for Civilization with some narrative popups thrown in – which is not inherently an issue. The actual issues are from the poor UI and some underdeveloped mechanics, along with a somewhat disappointing campaign and reduction of memorable narrative elements. If nothing else, Frostpunk 2 is worthy of discussion around developers being brave and making drastic changes to their franchise, rather than playing it safe.

Comments

Comments