Creaks Review

A pixel-perfect, painstakingly painted, pleasingly peculiar, puzzle-platformer

Amanita Design have focused on bite-sized adventure games in recent years. Chuchel was a whimsical series of puzzle screens in search of a cherry. Then Pilgrims reverted back to more of a traditional point-and-click adventure but with character swapping and an emphasis on replaying puzzles. Creaks is a marked diversion, not just because it is double the length of both their previous games combined, but because it’s actually a puzzle-platformer. The first clue to this change is the lack of a mouse cursor—the game works best with a controller. Despite the shift from their typical approach, Creaks is actually a great puzzle game.

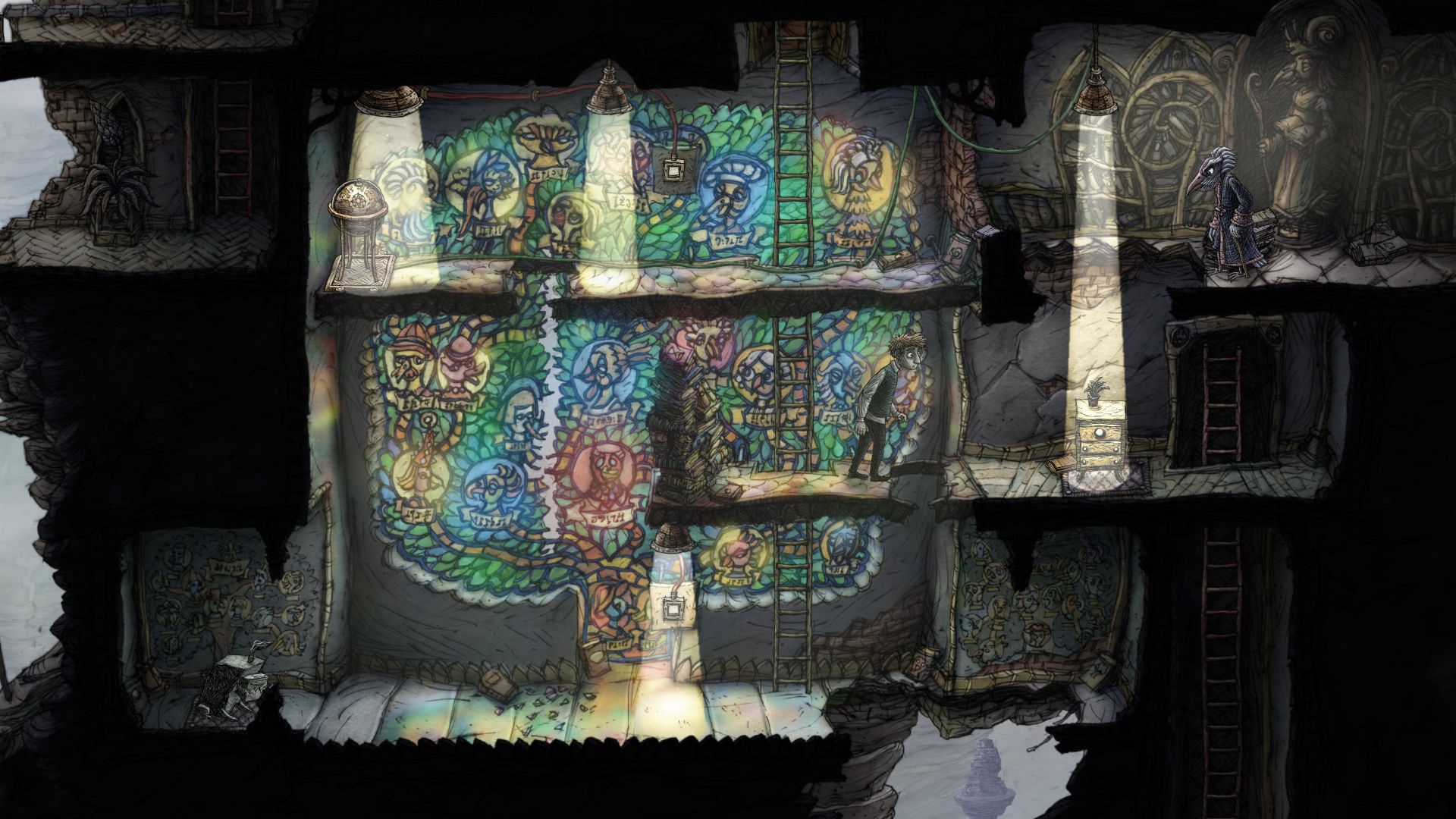

Creaks has no text or dialogue, so it relies on animations, world design, and unusual sounds to tell the story. You play as a young man who discovers a hatch behind some peeling wallpaper in his room. Behind the hatch is a tunnel that leads into an enormous cavern. Central to the cavern is what can only be described as a gigantic misshapen building (or house) consisting of dozens of levels, connected by ladders and elevators, stitched together in a jigsaw fashion. You enter from the top of the building, and the sprawling layout entices one to dive deeper.

As you progress, loud crashing sounds and a huge clawed limb indicate that a sizable monster is terrorizing the building. Several humanoid bird creatures reside within and they are trying to stop it from destroying their home; a warrior bird tries to fight it with a paltry slingshot while a scholar seeks a special book that might provide a more realistic solution. So you pursue these birds down through the floors, as they avoid the strange monster, and hunt for a book that keeps falling between the cracks.

Chasing after the book means passing through several challenges. Vicious dogs will give chase if you get close, and they often guard the ladders. But if they get caught under a cone of light, they transform into a harmless chest of drawers that you can either climb onto or drag over pressure switches. Deadly jellyfish float about too, up and down, until they too transform into something equally harmless under a light beam. Goats will run away, although they will attack if cornered, and they become chairs under light. Light is not just a means of converting these threats into furniture, it is a safe spot from dangers.

None of these sentient threats will willingly enter an active light beam, so some trickery is needed to trap or convert them into harmless forms. Light can isolate dangers from the main path, while you do something else. Wall switches can move platforms or turn on other strange devices. And eventually the game gives the player a remote control to activate various mechanisms from afar. So it is like a giant 2D sliding puzzle; move the pieces, neutralize any threats, and clear a path to the exit.

As you descend deeper, the challenge becomes more like solving two different sliding puzzles because spiky-haired doppelgangers either replicate or inverse your movements. Bumping into them is dangerous, but often they are physically separate from the player. And light turns them into docile coat-hangers. Unlike the earlier challengers, these doppelgangers require exact movements. Making iterative steps back or forward is essential to place them on switches or behind barriers. But for this placement to work, it means moving them against walls and taking extra steps to offset their position. The precision of these later puzzle solutions is delightful.

Like Valve’s Portal, the learning curve and introduction of new mechanics is close to perfect across the six hours. Little tricks are taught in almost every section before they are put into practice and expanded upon. The deadly forms of furniture are also combined smartly. None of them are overused. What is most telling about the efficacy of puzzle design is how often the number of interactive objects is minimal—maybe just a few switches—and yet trying to move everything into position takes some thinking. Pleasingly there is great satisfaction when solving almost every puzzle.

Paintings on the walls are a neat diversion, and they are usually found in the hallways between the main puzzles. Some are hidden in secret rooms. Most paintings are just great pieces of art by themselves, with intricate framing, depicting bird people or other quirky scenes. Push a button and certain objects within the painting will move alongside a tinkling music-box accompaniment. A second type of painting is an interactive mini-game that is like a marionette theatre or puppet show. These mini-games range from sword-fighting to jumping fish through hoops. This latter type is basically a sampler of Amanita’s more recent games and a great way to refresh the brain. Regardless of the type of painting found, each one is a reward.

The sprawling building/mega-house is incredibly detailed and captivating, and it gets more intriguing as the game progresses. Like one of those huge cross-section books illustrated by Stephen Biesty, it is like peering into a mysterious foreign world. From claustrophobic attics to sprawling libraries, the backgrounds are littered with twisted clutter that is more akin to exploring a museum at night or creeping through a hunter’s trophy room. Foreground shadows wiggle and eyes on statues keep watch as you shuffle down the twisted corridors. The sheer volume of detail overwhelms the eye and never ceases to amaze.

Music is even better than the world design. Mixing orchestral with the industrial, the tunes are quite reminiscent of the excellent soundtrack from Machinarium. Standard instruments like the clarinet, harp, and drums mix with unknown twangs to make bouncy compositions that are suitably quirky to match the abstract world. The music also escalates when you put all the puzzle pieces into their rightful spot, which can make it hard to leave a solved area when a particularly good tune reaches its final form.

Creaks is a different beast than Amanita’s usual experience, but it is an extraordinary puzzle-platformer with great depth. Taking just under six hours to complete, each mechanic is carefully introduced and put to good use in challenges that have a perfect learning curve. Solutions are satisfying because the tricks are subtle. With intricate and twisted world design, and some fantastic music, the entire presentation is up there with the best from the developers. Creaks will please fans of Amanita’s previous games and anyone who enjoys a good twisted puzzle.

Comments

Comments