Shadwen Review

A hookshot in the dark

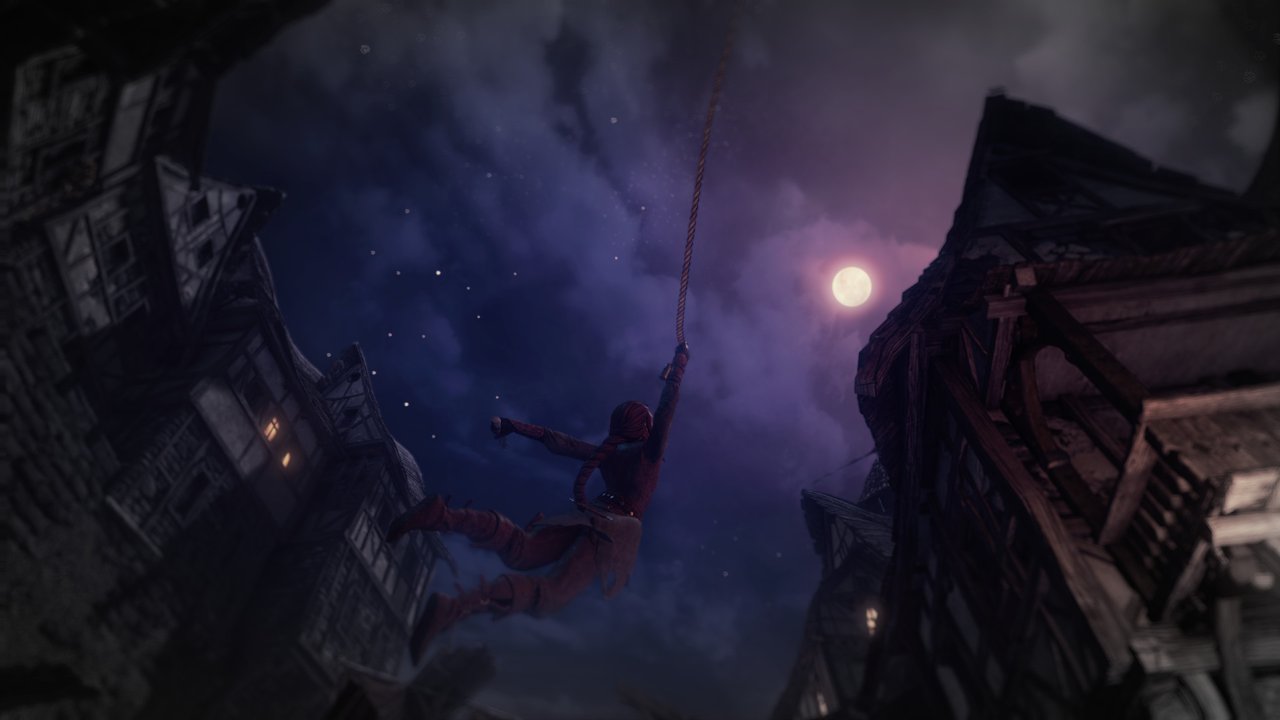

In the past I've often asserted—usually with the air of a facetious scamp deploying his finest hyperbole—that there's no game on this planet that couldn't be improved, in some way or another, by the addition of a simple grappling hook. What other gadget can promise to add so much with nothing more than a simple rope constraint? You get interesting mobility, shaped by momentum and gravity and the subtle vertical details of your surroundings, but you also get catharsis, either from the damage inflicted by the things you pull towards you, or the damage you inflict on yourself as you swing bodily into the side of a bridge support. There are so many ways the grappling hook can behave; so many rules to be defined for its behaviour, and the marvellous thing is that no matter what those rules turn out to be, there's bound to be a creative application for it. Thus my attention was snared by Shadwen, a stealth game with a backpack full of ideas that picked up the humble grappling hook, studied it for a moment, and eagerly stuffed it in with the rest of the mechanics.

And what a strange grab-bag of mechanics it is. You are the titular Shadwen, a humourless no-nonsense assassin on a murderous mission in the land of knights and castles and preposterously brutish slowly-patrolling guardsmen. Like the chap from F.E.A.R., you have the totally inexplicable ability to manipulate time—in this case, being able to freeze and rewind it as often and as far as you like—and also like the chap from F.E.A.R., there's a nasty little girl hanging around making your job a bit harder than it ought to be. Shadwen accidentally reveals herself to a poor gutter snipe called Lily on the way to stab the new King, and rather than doing something sensible—like, say, cutting out the girl’s tongue and locking her in a broom closet—Shadwen’s Other M instinct kicks in and forces her to take inexplicable pity on the child, letting her tag along for the journey. Presumably her conscience doesn’t extend to the women and children who will inevitably perish in the winter because she just gutted the family breadwinner on his night shift.

Anyway, back to grappling hooks, which are a much more reliable and entertaining investment than children. Like the rest of Frozenbyte’s catalogue, Shadwen is a game with an endearing Half-Life-2-esque fascination with using physics for absolutely everything it can; an infatuation that manifests through your ability to drag props around, swing from overhangs, and generally behave like a bargain-basement Rico Rodriguez without the snazzy accent or parachute-farting capabilities. There are a few sticking points here, though; the grappling hook will only latch onto wood, or more specifically, bits of geometry that the game has officially acknowledged as wood, which isn’t always the same thing. Physics engines also have a history of being about as consistent and predictable as a litter of excitable puppies when dealing with anything more complicated than two cubes stacked on top of one another, and while this is all very well when chaos is the end goal—ragdolls sailing through the air, oil drums exploding, walls collapsing into dusty piles of poorly-mortared bricks—it’s not so welcome when you’re in a genre that punishes a lack of precise, careful, well-timed manoeuvres with a crossbow bolt to the face.

The odds of pulling over a stack of crates or swinging from a balance beam and getting the exact outcome you want in Shadwen are every bit as disappointing as you’d expect, which is why the ability to pause and rewind time at will—far from being a gimmicky replacement for the quicksave button—is weirdly crucial, letting you carry out your plans exactly as you envision them with a bottomless supply of trial-and-error on tap. From a pure design perspective it sounds shockingly inelegant, introducing an entirely new mechanic to patch up the problems inherent in the basic gameplay systems, but to Shadwen’s credit it does let you execute some pretty slick moves without putting training wheels and safety bumpers on the physics engine to constrain what you can and can't do. Like many systemic stealth games, the best moments are those that clearly weren’t anticipated or designed by the developers, and that sort of thing simply couldn’t happen if Shadwen was designed to perform perfect Assassin’s Creed acrobatics at the push of a button.

Time travel is a nuanced mechanic, though, with a list of adverse side effects that outstrips most experimental antidepressants. The thing about being able to simply rollback any mistake instantly, without any penalty whatsoever, is that there’s no real punishment for failure in Shadwen; the game automatically puts the brakes on any trainwrecks-to-be whenever you take your hands away from the controls, and with the touch of a button you can revert to whatever point you wish, preferably one when everything was still decidedly less pear-shaped. That’s not to say that Shadwen is too easy or anything—on the contrary, mistakes that actually raise alerts reveal that the guards’ boorish nature does nothing to detract from their ability to nail you against the wall mid-swing with a single crossbow shot—but there’s no tension to be had when the game effectively hands you a save-scumming machine on a silver platter. I started off playing Shadwen as my usual cautious self, but before long I was running headlong into every area with the reckless abandon of a medieval streaker with a terminal disease, knowing that being inevitably shot through the head would no more inconvenience me than stubbing my toe on a protruding cobblestone.

Then there’s the whole matter of having to drag a snotty child throughout the entire game. For those raised on a diet of mid-2000s action-adventures, I can imagine that a six- or seven-hour-long escort quest probably sounds like a very specific kind of digital Hell, but Lily’s presence in the game is, in all honesty, a surprisingly smart touch. The game’s fondness for vertical vantage points, combined with the guards’ collective syphilitic blindness, allows Shadwen to go almost anywhere she pleases without a trace, crawling around in the eaves safe in the knowledge that nobody ever thinks to tilt their head slightly above the horizontal plane. Lily, however, is a street urchin, and not the resourceful kind that can vault fences and knock policemen’s helmets off, either; it’s all she can do to toddle slowly from hiding place to hiding place, so it’s up to you to clear the way, one way or another.

It’s a remarkable head-on collision of stealth gameplay styles that actually kind of works; Lily is the ball and chain that forces you to engage with the obstacles in your way, rather than just seeking out the one specific path that lets you circumvent them entirely. Many stealth games with pretensions towards ‘freedom of approach’ will allow you the option to quietly ghost your way through everything if you just navigate carefully enough, but in truth, this usually just serves to make most of the mechanics moot; Shadwen offers a clever compromise. It’s easy to see how this kind of setup could turn Lily into an infuriatingly incapable deadweight with all the likeability of an electric ankle bracelet—don’t worry, we’ll get to that in due time—but with the exception of a few minor stumbles, I found I could more or less let her just operate independently without fear of capture. As long as there’s a reasonably safe path guaranteed to make progress, she’ll usually take it, and she’s uncannily good at staying undetected when the guards are on the prowl, though that might have something to do with the way they look through her like she’s trying to sell them copies of The Big Issue.

And of course, it was only a matter of time before Shadwen tried to tackle the old chestnut of choosing whether you’re going to cut a patrolling goon’s jugular or send him to the land of sweet dreams with a sock full of anaesthetic fairy dust. Early on, the game rather tactlessly nudges you and holds up a sign telling you that killing people in front of Lily will have repercussions on the story, a message that might as well read “we're going to slap you with the bad ending if you get too stab-happy, matey” in gargantuan neon letters over Times Square to anybody who has played a video game lately. Unfortunately, if you want to get any fun out of Shadwen then that's a slap you're just going to have to take, because the game's actual non-lethal options are about as varied and satisfying as an all-you-can-eat buffet for Vaseline tasters. Of the various gadgets you can assemble, the majority of them are of a distinctly murderous nature—you’d almost think that Shadwen is an assassin or something, huh?—and while it is kind of fun the first few times to distract a guard by jiggling a nearby crate around with your grappling hook, the joy quickly fades when you realise that that's going to be the only technique at your disposal for the next however many hours. Perhaps the idea was that players should feel compelled to engage in the uphill struggle of doing a non-lethal run rather than taking the easy way out and bathing in the blood of their enemies—which would, after all, be a damn sight more interesting a dichotomy than just making two equally attractive routes—but ultimately we’re going to loop around to the universal sticking point: I came here to have fun. You’re not going to get me to take the high road without a seriously compelling reason.

That reason is probably supposed to be the relationship between Shadwen and Lily, around which the story revolves as you gradually inch closer to your target. There’s potential for an interesting character piece here, perhaps placing Lily’s childlike view of the world against the political forces that guide Shadwen’s hand, or watching Stockholm Syndrome unfold in a stressful situation, or—if you really want to hammer that whole ‘don’t stab people’ thing home—the allegorical conflict of a child trying to spite the guardian figure who protects and guides them. What we get instead is… well, a big load of nothing, really. For obvious reasons, dialogue between the two of them isn’t an option while they’re sneaking through the streets of Genericfantasyopolis, with background exposition provided by oblivious pairs of slacking guards, so the entirety of the game’s character development consists of voiceovers crammed viciously into the loading screens bookending each chapter.

Unsurprisingly, this leaves both main characters about as fleshed-out as the actors in a Hungry Jack’s radio advert, and about half as likeable. Shadwen never really breaks her ‘cold, tough heroine’ shtick—because we all know nothing makes a character cooler than a total unwillingness to emote, or display strong opinions—while Lily just sort of perpetually ping-pongs between childish curiosity and simple-minded moral preaching, neither of which provoke much of a response. Maybe if I’d been a non-lethal pacifist angel without so much as a parking ticket to my name, their exchanges might have been more engaging, but there’s no point holding characters hostage like this before going to the trouble of making me care about them. It’s like putting a gun to the head of an inflatable doll and threatening to pull the trigger; am I supposed to be haunted by the “pffffweeeeeeeeeoooooorrrrp”?

Fortunately Shadwen's stealth is enough to carry the game—or at least, suspend it from an infinitely strong rope constraint—all on its own, a feat that'd be a lot easier to applaud if it didn't take so long to roll out of bed and wipe the sleep gunk out of its eyes. The level design opts for linear chains of self-contained arenas over Thief-style non-linear missions, a constraint that's understandable given that the latter would mean you could just leave Lily to play with a couple of twigs in a bush and return to pick her up from the medieval daycare several hours later, but by the time these arenas reach the level of size and complexity that actually lets you get creative—rather than working your way through what feels like a series of overlong tutorial levels—more than a third of the game has already slipped away. Loot chests full of gadget blueprints and crafting materials are scattered throughout the levels, and while it’s nice that they’re used as incentives to explore or deal with difficult groups of guards, your arsenal of sharp things—and consequentially, options—is going to be disappointingly limited until you’ve found a sufficient number of them. It doesn’t help that variety is not Shadwen’s strong suit; you’ll be dealing with the same level elements, enemy types and uninspired dry fantasy environments for a very long time indeed before the game finally starts rummaging around in its bag for something new to throw at you. Frozenbyte actually threw in a pretty powerful level editor with the game, a stunningly generous move that could probably rectify a lot of my issues with the level design, but somehow it’s hard to visualise many people being enamoured enough with Shadwen to bother taking a run at the program’s difficulty curve.

Shadwen is an interesting beast, one that deserves more appreciation and scrutiny than it’s probably going to get; a unique stealth experience that interweaves a grab bag of seemingly-disparate mechanics into something surprisingly cohesive. There’s a clever core experience in here somewhere, poised to unfold into a barrel of chaotic, creative, sneaky, physics-driven fun, but it never gets the room to grow into something truly great, smothered by a blanket of inconsistent level design, astonishingly janky controls, and a severe lack of imagination. If the writing was a person, it’d be the kind that clearly doesn’t want to be here, and as usual, the dichotomy on whether to murder people or not only serves to detract from the experience, leaving us with nothing but a tired, mouldy, last-gen claim of “your actions have consequences!” to sigh exasperatedly at. I’d still recommend Shadwen, if only as an intriguing stealth experiment with some gleeful rope swinging and physics-driven violence neatly packed in, but if the concept doesn’t grab you, feel free to let it slink on by.

Comments

Comments