Brave New Worlds

The concept of open world games has evolved over the years from its somewhat humble beginnings in older generation games such as Ultima and Elite, to the sprawling sandbox worlds of Skyrim, Far Cry, and Grand Theft Auto, to name some heavy-hitters. When we think of open world games, we imagine vast spaces that allow us freedom of choice in the way we handle objectives, where we choose to travel in the world, and amount of “stuff” with which we can interact. Varied locations, side-missions, interesting design, and the overall size of the world all factor in to our expectations and interpretations of what constitutes an open world.

Open world, with the emphasis on the “world,” primarily constitutes epic, expansive environments, and what better method to showcase a new game or console than by including an immediate visual benchmark for the scope of our game, the console’s potential, and our expectations. The idea that “open world = involved and lasting adventure,” harks back further than visual media and books to Neolithic campfire tales. You’d look up at the stars (hoping a bird wouldn’t steal your child) or across rolling expanses of unknown and dangerous territory ahead of you, and wonder what it had to offer. There’s an innate desire to explore and discover the unknown that’s kept us progressing for millennia.

In the context of story and media, the “Ur” example of an open world adventure would be Beowulf or The Epic of Gilgamesh, ancient tales that spoke of heroic deeds sprawling across foreign lands. The notion that open world breeds big adventure is also evident in literary space operas and high fantasy where, we, as a reader, are thrown into a giant world or universe that begs for exploration. The sense of in-universe scale projects expectations onto us whether it’s games, literature, or film, and it’s the medium’s job to rise to those hopes and dreams.

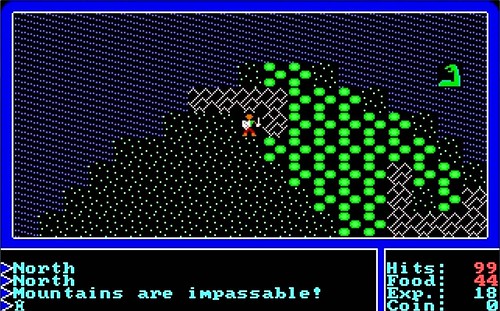

To examine the concept from a purely console-based perspective (though they were on PC), perhaps the first clear example of the open world game would be the aforementioned Ultima 1: The First Age of Darkness or the space simulator Elite. With the advent of the 128-bit era, developers had more to play with to fully realise and redefine the idea of open world gaming. The use of a loose narrative and distracting environments in games like Grand Theft Auto and The Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall has survived later incarnations as well as the rest of the western market.

During this era, we had Fable (Project Ego/Hubris) courtesy of shiny-headed beacon of hype, Peter Molyneux, which gave us an insight of how the concept differs dramatically from its inception to finished article. For one of the first times, the gamer had the chance to see how difficult it is to stay true to the imagined and hopeful design. We were promised growing trees and stylised real-time environments, but in the end, while still an excellent game, was a far cry from its open world intention.

Another sob story of open world woes came from Shenmue’s costly design process that can be viewed as the advent of cost and time becoming a defining factor of the genre. That, and it brought back dreaded QTEs. Shenmue cost seventy-million dollars and while a critical darling, disappointed in its sales, showing how badly giant games can flop. Compared to the 1.3 million Shenmue sold, Shenmue 2 only sold around 400,000 units. For any other, cheaper game, this would be considered a success, but in the open world arena, it just didn’t cut it.

Like any new industry or industrial arm, they were on shaky ground; still testing what the platform was capable of, balanced with what consumers wanted. As time and technology progressed, so have gamers and developer’s notions of what an open world should be. With each new generation we have improved graphics, higher computational power, and more usability, so as consoles become “bigger” (in both senses of the word) so, too, should the games. Right? Does the size of the world affect our enjoyment? What is the right size for an open world game on a console? Will the next iteration of Fallout be larger than Washington or Las Vegas? We expect it to be simply because it’s the next game in the series.

What some of us fail to factor in is that open world games consume an inordinate amount of time. An Amiga, Commodore, SNES, or older PC open world may have taken time with sprite/game design, planning, and placement, but there is obviously a huge gulf between a lower-bit era concept of open world and today. With dev times and cycles increasing exponentially with each console, open world games are simply going to be harder to create and budgets will continue to soar. In Hollywood terms, the GTAs and Skyrims are the Michael Bay/Roland Emmerich of games: hulking monetary goliaths that devour time and cash like starved child eating his way out of barrel of popcorn. The stark reality is that if an open world IP desires to break the scene, then without the backing of a major studio or some serious belief on investors’ behalves, independently developed open world games are only going to struggle further as time progresses.

Skyrim and GTA cost millions of dollars to create expansive adventures and they weren’t perfect (although highly lauded in most cases). Their worlds were criticised due to repetitiveness, limited variety of side quests, and scaled back features. Some found Skyrim lacked a sense of life and personality; a monochrome landscape filled with strange talking people and that bloke who won’t stop banging on about the Cloud District. Some found GTA V’s lack of repayable heist missions, buildings you couldn’t enter, and map size as points of contention. All these, while fair criticisms, have a habit of falling slightly mute when put in the context of what these companies have produced.

What isn’t perhaps fair, and most certainly infuriating, are games message boards after the release of sandbox games. You’ll visit a site, against your better judgement, and find a shiny nugget of truth floating beneath the effluence. The effluence consisting of “You know what would be cool/a good addition/should have done?” What, anonymous forum poster? What earth shattering insight do you have that does not factor in design time, planning, production, and cost, that can magically be inserted into the game with ease? I tell what can magically be inserted with ease, anonymous forum poster.

Common sense. It’s not as if studios can round up sign touting vagrants with “will code for hot showers” and whip them into creating new content that you and several other people think the game must have and was foolish not to include. It doesn’t work like that. Darlings die bloody deaths. A studio doesn’t function like a mad man’s imaginarium fuelled on Red Bull and smiles. It just doesn’t. Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning was a recent sad reality faced by the developers. While the game sold over a million copies, and had EA as its publisher, it didn’t save the Providence-based 38 Studio. Open world games can’t afford to skirt the cold, hard bottom line, they have to vault over it. It’s a genre where only the strong survive.

However, it’s not always so bleak. The first Assassin’s Creed, while somewhat flawed in its repetitiveness, showed that the genre was very much alive and at home on then-next-gen consoles. It’s since become a powerhouse or dead horse depending on which side you’re on. But based on the recent Black Flag offering, AC is very much arrr-live. Similarly, Crytek’s Far Cry blew gamers out of the water upon its release from a relatively unknown company.

Then, we have games that tread the water such as Two Worlds: 2, the little game that could. I loved it. I loved its ridiculous open world made on a budget that pales in comparison to the giants in the industry. It had faults, but I felt as if I was going on a big, dumb open world adventure. Within half an hour, I was wailing on a rhino while dual-wielding swords, then being stalked by a cheetah, only to end up in a small fishing village taken over by lizard men. Thought had gone into a creative magic system, weapon crafting, and item crafting – the devs threw everything they had at the game, and while never perfect, was stupidly enjoyable.

There’s a quote in literature that goes something along the lines of “A finished work will never be as perfect or realised as the initial premise.” These games, while perfect on a drawing board, with the myriad of cool options, features, landmasses, will never make it into the game because of the constraints of time and money, which will only worsen. Is it perhaps, then, that open world is dying?

No. Of course, not. Well, not for big developers, at least. Assassin’s Creed, GTA, Fallout, Oblivion, Just Cause, Red Dead Redemption, Far Cry – they make great returns and are always GOTY contenders. It’s simply that with the cost that comes with the genre it’s increasingly difficult to create open world games. The best chance in the near future is with new consoles where new IPs are waiting to be gambled on, so it’s not too farfetched to imagine the next series giant is just around the corner. However, we’ll see a decrease in the number smaller studios releasing these games for next generation based purely on cost and expected returns.

Looking at the prospective line up for the Xbox One and PS4, we’re still getting our open world fix, however, the likes of Mad Max, Sunset Overdrive, and Sleeping Dogs sequel being the leading new IPs from well known studios. The closest from relatively unknown studios will be Team Bondi’s Whore of the Orient and Reach Studio’s Project: Heart and Soul, which will be the biggest gambles for the genre on next generation consoles.

But in time, our notion of open world needs to be tempered. Games on such a large scale will take longer, they’ll cost more money, there’ll be more features left on the cutting room floor because of the nature of the industry. We want games quick. Company execs want games quick. And with big hits taken to several new IPs this console cycle it doesn’t work in favour of smaller studios. Perhaps in the future, like with Team Bondi’s L.A. Noire, big studios will delegate larger projects to smaller studios in the hopes of taking a chance and allowing these studios to “test drive” their ability to develop new games. However, it’s the developers that ultimately pay the price and have to struggle to produce a game for an audience that sometimes loses focus (or is ignorant) of the process. But the future won’t be so bleak, there’s still worlds out there just waiting to be discovered.