Darkout Review

You have to feel sorry for Darkout. Of all the times you could have released a space-themed Terraria clone, I can’t possibly think of a worse time than the coincidental beta release of Starbound, the space-themed Terraria clone that – crucially – people have been excited about for over a year. Even before it’s out of the gate, Darkout has been overshadowed so hard that its grandchildren are going to suffer from vitamin D deficiency. It’s a shame, too, because while Darkout probably isn’t going to end up on anybody’s Christmas list, it does do a few things interestingly enough to merit acknowledgement.

For instance, at this point in the review I usually ease myself into the groove by describing the story as off-handedly as possible – you know, since it lets me put off actually making any sort of meaningful commentary – and the twist today is that despite Darkout’s pure sandbox heritage, that trend is going to plough right on through. You play a nameless characterless prat with a plasticine haircut who gets marooned on an alien planet thanks to an unspecified calamity and if you like then you could leave it at that. However, if you pay attention to the tool-tips, ransack the flaming cargo palettes that occasionally rain down upon the landscape for data logs and listen in on the errant radio signals that cross your path, then you can piece together a far bigger story, and even work your way towards something that resembles a definite ending. In essence, the game allows you to choose how immersed you become in the story, whether you want to get off the planet or just live an idyllic life in a home base shaped like a giant brontosaurus. I just know that this is going to be taken out of context, but it kind of reminds me of the System Shock games, albeit with considerably less linearity and completely different gameplay, of course. It probably helps that a lot of the data logs have more than a bit of a horrific air to them, but you see what I’m getting at.

Here’s the thing, though. I’ve been sitting staring despondently at my monitor for a little over a week, rolling my head across the keyboard every now and then, and I still can’t decide if Darkout’s usage of a story is something to be showered in rose petals or kitchen swill. Part of what drives the appeal of games like Minecraft and Terraria has always been the fact that they’re direction-free, allowing the player to do as they please without the overbearing sense of defying the developer’s intentions. Adding a set of definite objectives, even those you are never obliged to pursue, can only diminish from that sense of freedom. On the other hand, I can’t be the only person whose recent Minecraft exploits consist solely of logging in, terrorising the local wildlife and losing interest within five minutes because I’m more creatively bankrupt than a Channel 7 board meeting. These creative toys, or construction sandboxes, or whatever hopeless pigeon-holing term you prefer to use to classify them, quickly lose all appeal when you can’t think of a project to apply to yourself to, so perhaps having a goal to laboriously crawl towards is a point in the game’s favour after all.

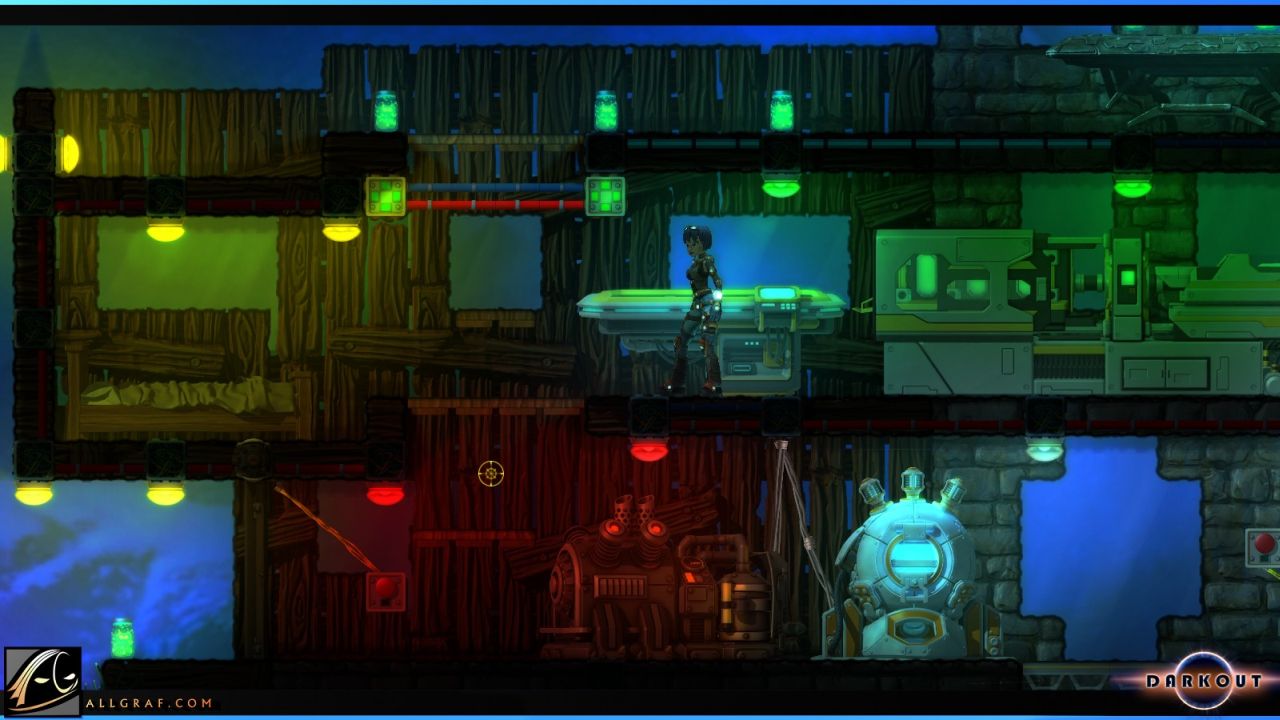

I’ll say this for Darkout though: there’s certainly no shortage of projects to undertake. While most of its brethren take place in a pseudo-fantasy time period that precedes the invention of the loom, and thus can be a bit dry when it comes to technology, Darkout’s sci-fi position allows it to go a little bit nuts. Take light sources, for example. Even a talentless fool with nothing to their name can slop a bucket of tar over a bundle of sticks and make a flaming torch, but the more discerning survivor will fill jars with glowing alien mucus and plop them down, or assemble a camping lantern, or create a fully-functioning electrical grid and hook up some restful mood lighting to it with the option to have it trigger when they come home from a hard day’s surviving. In less obtuse terms, the number of recipes available is mattress-chewingly insane. You really can engineer some quite elaborate contraptions by stringing the various craft-able items together, making the game considerably less like a box of Lego and more like an electronics set for the terminally psychotic.

Chances are, though, that you won’t end up engineering anything quite so elaborate, because the actual crafting system is tripe on a damp biscuit. I’ll be the first to point out that having to obsessively check the wiki every few seconds to find the necessary recipes was the absolute worst part of learning to play Minecraft, but it was at least functional. Darkout’s approach is akin to curing a minor cough with a chainsaw tracheotomy. You can’t craft anything until you’ve researched its blueprints – which is actually a decent idea in itself – but blueprints can only be researched once you have acquired a significant number of the materials that they use. If you want a specific blueprint – and you will soon enough, mark my words – your options are to either amass so much arbitrary junk that the game clues you in, or try to guess combinations like you’re in the world’s worst point-and-click adventure. Or, if your brain has not recently been submerged in nitroglycerine, you’ll look up the recipes on the wiki, thus reducing the entire asinine system to a single extra step. On top of this, researching an item’s blueprint consumes the materials that it describes, so if you want to create a resource-expensive item which contains, let’s say, a Fabergé Egg and three pints of unicorn tears, then you will in fact need two eggs, and probably an extremely generous unicorn. Better still, some items can only be acquired by smashing randomly-dropped crates, so even the best-laid plans can be thwarted with the gods of RNG aren’t smiling upon you. All of these are just meaningless barriers between me and the things I want to build, when acquiring the resources in the first place is already taxing enough a task. Why, Darkout, do you take such joy in flowing as smoothly as month-old custard through a straw?

In all honesty I’m quite perplexed, because while the crafting system shows only regression, Darkout displays encouraging signs of learning from its forebears in its subtler mechanics. For instance, somebody finally realised that having half your hotbar being constantly taken up by your assorted catalogue of everyday tools – pickaxe, axe, shovel, sword, corkscrew, Geiger counter – is a sure-fire way to crack the player’s micromanagement prospects across the shins with a steel baton, so now we have the all-purpose ‘auto’ option, which simply lets you hold the mouse button down and have the game select the appropriate tool for whatever you’re trying to destroy, shift or uncork. It reeks of contextual gameplay, a trend that has been responsible for the oversimplifying of many once-proud games, but here I think it’s actually appropriate. After all, I think it can be taken as read that if I’m trying to cut down a tree then I understand that I need to use the axe, and not the pair of nail scissors. Darkout also hits upon the bright-spark idea of having the hotbar retain separate slots for the left and right mouse buttons, allowing a total of twenty different assorted inventory items to be accessed without ever having to touch the inventory screen. It, too, works really well, and is therefore not worth dwelling on further.

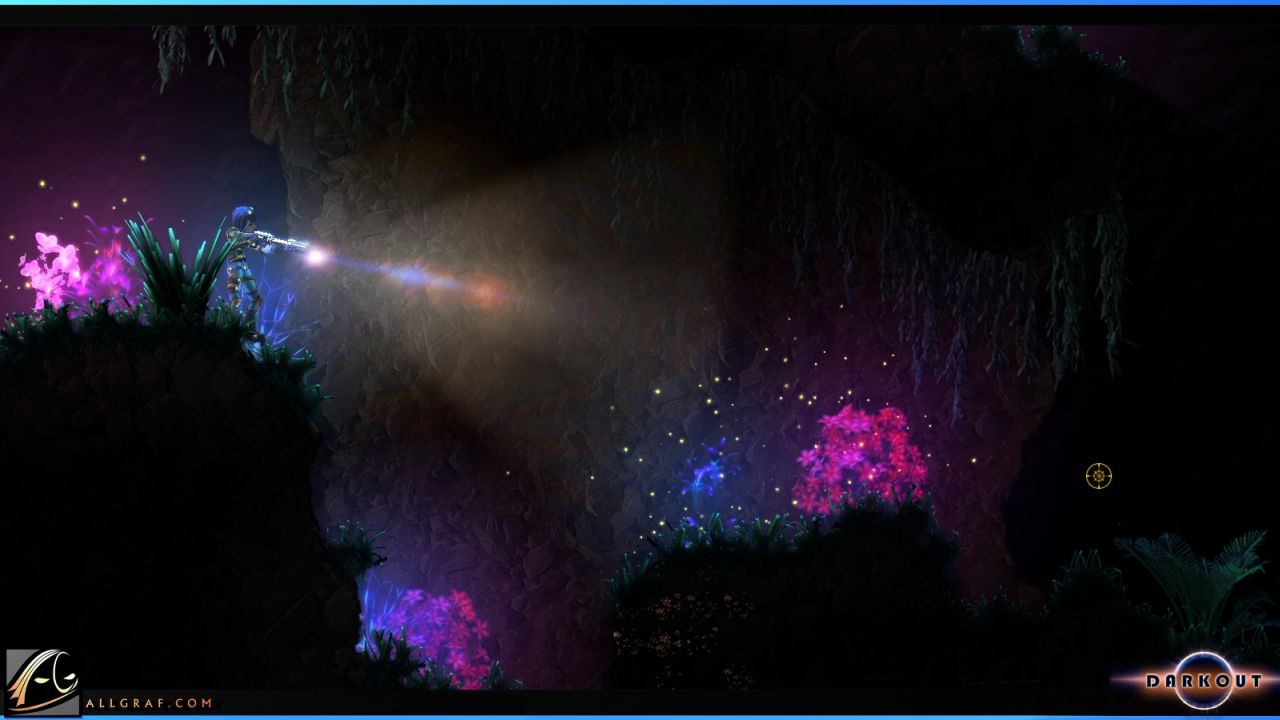

What doesn’t work so well is the combat system. Clarifying statement: there isn’t one. Now, Darkout’s kin have always had woeful combat, wherein you inorganically swung a sharpened stick frantically at a foe until they keeled over and died, but they too were at least functional. Darkout once again regresses in areas that I thought were essentially stable by removing any kind of knock-back from melee attacks, making it nigh-impossible to fight a single foe without having them claw off half your face first. You can still stun-lock some of them if you’re lucky, (and if they’re feeling generous, and it’s a Thursday) but the attack animations are so floaty that half the time you’ll just miss entirely and lose another quarter of your health bar in the process. Perhaps making melee combat so awkward is the game’s way of encouraging you to use ranged weaponry, but if so, why is it so sodding difficult to craft bullets? Darkout practically hands you a gun during the tutorial section, but once you expend the ammo you start with it’ll be several hours of gameplay before you’ve researched the necessary materials to re-stock it. It’s as if the game takes a certain perverse glee in drawing you in before turning your weapon into a useless lump of metal.

I might have been even more upset if Darkout’s approach to death wasn’t so careless. In broad terms, dying means nothing. You don’t lose your inventory contents and the game thankfully doesn’t have any shoehorned-in RPG elements, so you don’t lose experience either. With the only punishment being a small hit to the current hitpoints, what would normally be considered a minor setback now becomes an outright helpful tool. I ended up frequently throwing myself off cliffs to my death because it was quicker and easier than trying to trek back to my base across miles of hostile alien terrain, and without meaning to sound confrontational, the point where players start to abuse basic mechanics like that is the point where the game designer has to feel just a little bit ashamed.

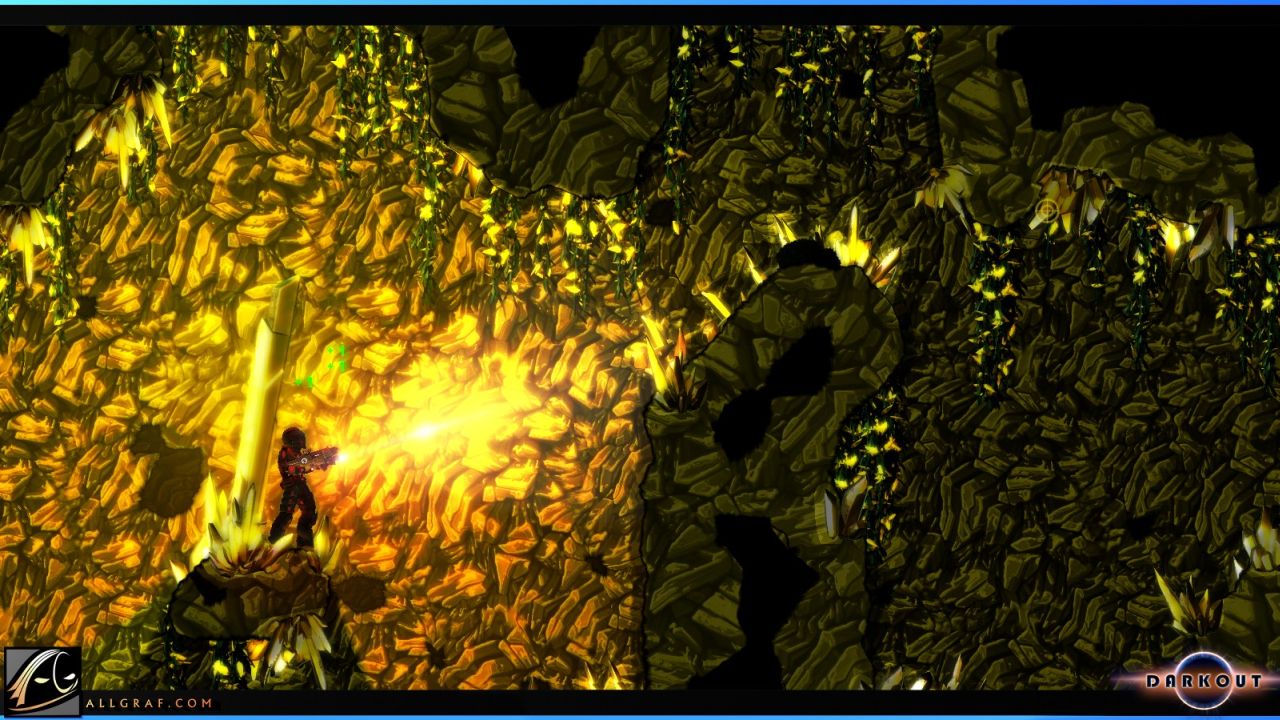

Darkout also has a severe problem with polish. Not an outright lack of it, as is quite common with games of its calibre, but a failure to distribute that polish evenly. I am not exaggerating when I say that it sports the best lighting effects of any 2D game I have ever seen, but the animations, as already mentioned, carry all the impact of a paper plane in zero gravity, and the visuals themselves bring to mind a trashy 90s CD-ROM adventure; a chaotic four-lane pile-up at the intersection of Sprite Street and Pre-rendered Promenade. I’m always pleased to see an indie game that doesn’t just throw up its arms and yell “alright, let’s do pixel art”, but Darkout’s alternative is just ill-fitting, like a sweater knitted by somebody with slinkies for elbows. Strangest of all, there’s also a very real problem with being unable to traverse tiny bumps in the terrain without hammering the jump button. Normally this would be typical for a Terraria-like game, but the actual smoothness of the terrain makes it look terribly incongruous. Of course, it’s possible to look past a lack of polish, but it becomes increasingly difficult with the amount of repetition involved, and looking past it only introduces you a game that is, when all’s said and done, really not at all well-designed.

Actually, can we take a moment to thank the unnamed ancient chap who first proposed the scientific method? Without it, you see, this review would not exist, because it was only through rigorous experimentation that I could say half of my criticisms with any degree of certainty. It really is astonishing how little the game tells you. It has a tutorial – something that is, in itself, comparatively progressive – but all it does is tell you the basic controls and primitive crafting, with no thought given to the obtuse research and crafting systems themselves, or how to use the plethora of items that they provide. Once again we have to resort to our old friend, the wiki, and my overall opinion of the game slips down a few more precious notches.

If it sounds like this review is unusually preoccupied with the smaller details, even by my own nit-picky standards, it’s because that’s all Darkout really does to set itself apart. The more I play them, the more it becomes apparent that these Terraria-like games dry up quicker than a beached whale on the surface of Mercury when they’re not being drenched in a concentrated stream of novelty. Darkout can provide that for a while, with its extensive crafting and intricate machinery, but it’s just too poorly presented and laced with bad design to match up when most of what it does has been done before, and usually done better.