Undertale Review

If there’s one thing Undertale isn’t very good at, it’s selling itself. “The RPG game where you don’t have to destroy anyone!” proudly proclaims the Steam store tag-line, failing to recognise that while this is technically true and adequately sums up the game’s most interesting system, it’s a bit like selling Doom with the line “the FPS where you do the Lord’s work on the surface of Phobos”; the connotations of the phrase all-but completely soil the appeal. Strictly speaking there’s nothing wrong with supplying a pacifist approach in games – Thief II just wouldn’t be the same if you couldn’t ghost your way through it – but it’s one of those things that tends to be in there just so people can say it’s there, you know? “Hey losers, violence is for people too clumsy to get things done the right way. If you’re a real hardcore gamer you’ll do this without hurting a butterfly.” The unspoken words, as always, are “provided that you really like extra-hard, no-fun-allowed challenge runs where you spend most of your time either running away or hiding in cupboards.” Like it or not, most games are built around confrontation, and subtracting that confrontation from their formulas is like trying to play a game of Monopoly with no scrappy plastic money. Undertale isn’t like that; it’s the kind of game where pacifism is not only a completely viable approach, but also – in the landslide of majority of cases – much more fun than just pummelling things into submission.

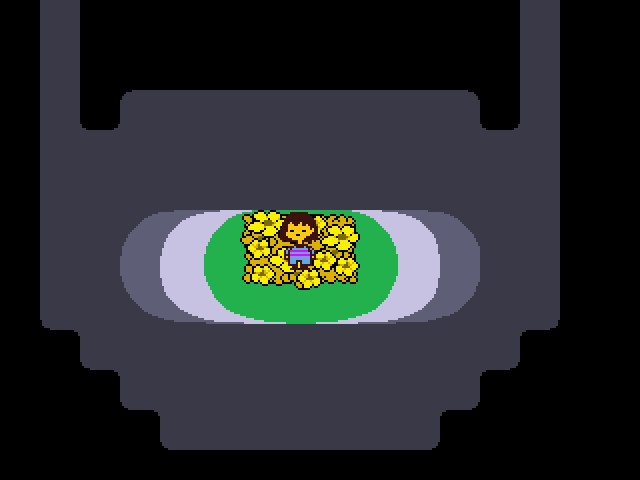

Oh dear, that’s not really selling it either, is it? Let’s try again. Undertale is, to be as succinct, blunt and upsetting to fanboys as possible, the game I wished Earthbound had been. Technically speaking I suppose it’s a JRPG, an experience normally only matched by downing a bottle of antihistamine and trying to do your tax returns while somebody watches cheap anime in the background, but all the elements that typically come with that label – random encounters, levelling up, taking turns to punch floating numbers out of each other – have been either toned down or transformed beyond all recognition to uphold an adventure that’s equally likely to leave you with an ear-to-ear grin or wake you up at four in the morning, drenched in sweat. You are a small, defenceless, expressionless child who has supposedly fallen into a subterranean world full of monsters – many of which try to kill you, but few of which actually want you dead, if you see what I mean – and your job is more or less to keep moving to the right until you find your way home. All very standard fare in the plot department for a fish-out-of-water fantasy, but the strength of the game’s writing lies not so much in the narrative as it does in its characters, its sideshows, and the strange artefacts it leaves lying in your path. It’s the kind of game that’s difficult to write about because it stays afloat almost wholly on its ability to have something fresh and delightful around every corner, and to discuss such things in any significant detail would be like starting a review of The Stanley Parable with a binary tree diagram of every choice you could possibly make. I could wax on for at least another page or so about ******’s fight and how she ****** her attacks ******* **** if you ***** ***** *******, or about the extraordinarily silly ****** sequence with *********, or the utterly bonkers ****** ******** with ******** after he ********** the **** ****** ********. But like all the surprises in Undertale, they’re best discovered by yourself. That’s why this last bit is censored.

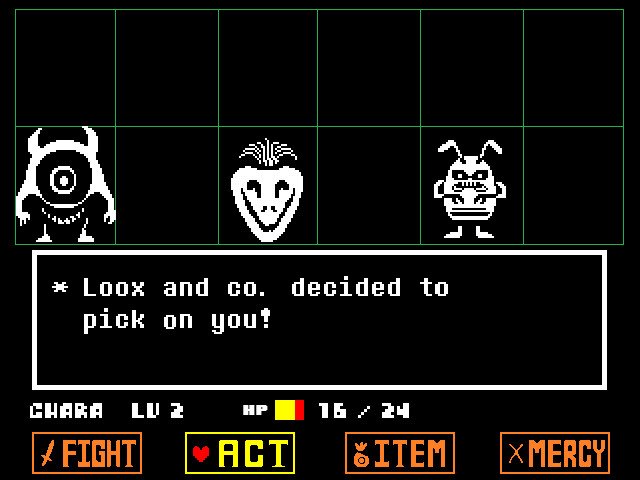

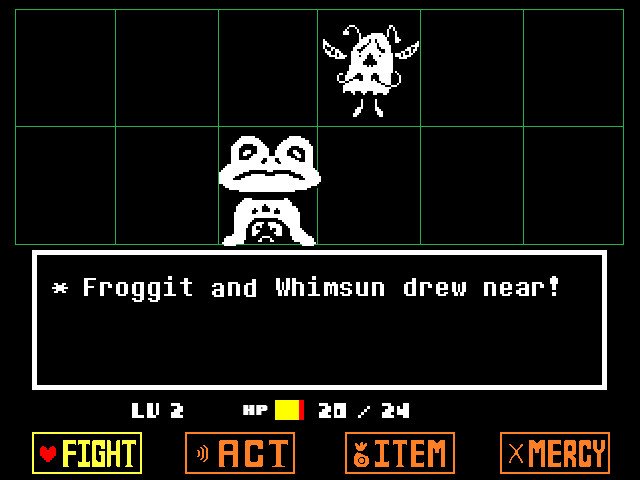

So let’s move onto something I can actually write openly about without being incurably wracked with guilt: combat. You can, if you really want, just hit an enemy until they die, timing button presses for bonus damage a la Paper Mario, and that’s all well and good if you’re the kind of person whose sandwiches only ever contain cheese and a bit of margarine. Undertale makes it pretty clear, however, that you’re missing out on the good bits. Every enemy you bump into has a highly distinct design, both visual and behavioural, and by opening up the ‘Act’ menu you can interact with them in various ways tailored to the enemy itself. Taking the pacifist approach usually means solving a lovely little character puzzle of sorts where you work out an enemy’s grievance – usually with clues communicated through their appearance or actions – and take steps to calm or otherwise neutralise them: you might have to laugh at somebody’s dreadful jokes in order to boost their self-esteem, play with an excitable monster until it falls asleep, steal the magic hat off somebody’s head or just outdo them in a show of bravado. Outside of the boss battles you can normally just fumble your way through these puzzles by trying whatever your gut says sounds about right, but like pretty much everything else in the game, the relative simplicity of the systems is obscured by the overwhelming charm of the writing.

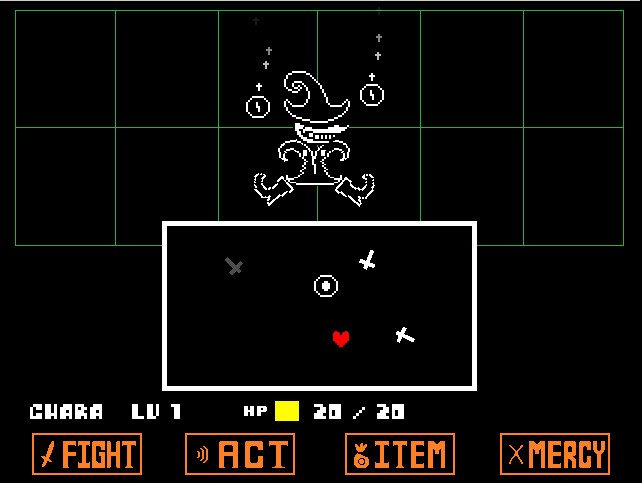

Of course, nobody’s going to withhold their attacks while you work out their psychological issues for them. Rather than just standing there and taking a beating, the damage you actually take is determined by how many times you’re hit in a little shmup-like minigame that pops up for a few seconds, where you must manoeuvre your soul – represented by a tiny pixelated heart – around projectile attacks generated by the enemies on the field. Attack patterns are usually themed around the enemies producing them – like, say, a pair of sentient vegetables showering you in bouncing eggplants – and can be combined together into some ferociously difficult patterns when you’re up against multiple foes at once. It’s a neat way of adding a hair-raising mechanical challenge into the usual mindless back-and-forth, and since the whole premise of ‘dodge things to not die’ is so simple and flexible, it forms yet another outlet for creativity in a game that already exudes it from every orifice. Projectiles can have any size, shape and pattern, so long as they can be dodged, and the variety in the monster designs means you’ll be assaulted by the likes of boomerangs, inverted crosses, bars of soap, literal teardrops, throwing knives, leaves, jets of flame, and on one exceedingly rare occasion, actual bullets. At times it can get a wee bit annoying since the hitbox of your soul isn’t immediately obvious, but since getting hit once or twice only takes off a few hitpoints at most, there’s usually not an awful lot at stake.

Anyway, let’s have another crack at the writing. Earthbound is once again the obvious comparison, with the weird character designs and cutesy exterior juxtaposed against moments of surreal dread, but whenever Undertale decides to be genuinely funny – fortunately a very frequent occurrence indeed – it has an anarchic silly streak reminiscent of the earlier Paper Marios or a less slapstick-y Jazzpunk. Absurd scenarios often seem to just pop up out of the woodwork, and the game’s lack of respect for the rules of continuity (or believability, for that matter) means that there really is no telling what might be one screen over. And it’s not ‘random’, either; there’s never a non-sequitur for the sake of a non-sequitur, not when a non-sequitur can divert you off on a fun little tangent where you’re on a cooking show with the cousin of the robot from A Grand Day Out. Obviously this causes the tone to swing wildly around like a set of pants on a flagpole, but somehow never jarringly enough to take you out of the experience.

I promise you I’m not cherrypicking here: there’s a bit where a character chugs an entire bottle of ketchup moments before delivering a question that throws an entire section into the game into fridge horror territory, and it works. It’s the kind of game where you’ll want to do a pacifist playthrough not just because it’s more fun, but because everybody is just so goddamn likeable that bringing yourself to hurt an enemy – even the boss characters – is genuinely kind of hard. On my first run I only intentionally killed one creature, and that was only after they tore the universe asunder and proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that they were too dangerous to be left alive. If there’s anything to complain about it’s that your own character is a bit of a cardboard cutout when it comes to personality, but hey, Portal 2 did the same thing, right? Surround a dullard protagonist with engaging characters that can carry the show all by themselves and it hardly matters that the player is piloting around an emotionless android.

It’s smarter than you’d expect, too. There’s a TVTropes page handily entitled ‘The Dev Team Thinks of Everything’ that lists all the times games cleverly catch out players’ attempts to break their logic, and by the end of next month I estimate that sixty percent of that page will be dedicated to Undertale. You can go back and save a character you accidentally killed, but the game will guilt trip you accordingly for not being able to live with your actions. You can deliberately fail the tutorial multiple times and your unamused tutor, fed up with being toyed with, will cut right to the chase. The way the game seems to know what you’re going to do before you do it – combined with the very personal, character-driven nature of its responses – can be more than a little chilling at times, if I’m honest. This game remembers things. Not the kind of systemic memory most RPGs have, where it’s obvious what matters, what’s trivial, and what’s beyond the scope of the game; this game remembers things you’d rather it didn’t. The underlying logic is probably just a big text document full of numbers somewhere, but the way it covers all the bases can make it look frighteningly intelligent, especially when indulging in the kinds of fourth-wall-breaking shenanigans that make Psycho Mantis look like a kid with a Magic 8-Ball. “You like Castlevania, don’t you?” Cute trick, Hideo Kojima. Now watch this character directly plead with us not to reset our save file because that’ll literally wipe them from the universe.

Chances are you will be resetting your save at some point, though; the thing about Undertale is that even though you can theoretically just finish it once and be quite satisfied – unless you’re some kind of android with an array of coprocessors where your left hemisphere used to be – it’s the kind of game that you really ought to be playing multiple times, if only to see the over-the-top maddening finale that is the true ending. Thanks to the game’s worryingly persistent memory, even identical runs made in succession can be subtly and not-so-subtly different – characters recognising you when they shouldn’t, permanent changes to the world, that sort of thing – and of course, there’s always a chance of finding some new area or plot thread if you just dig a little deeper here and there. You can only ever have one save file at a time, though, and it’s often completely ambiguous if your actions actually have an effect or not, which if I’m honest I’m kind of in two minds about.

On one hand, it gives Undertale a fabulous sense of mystery that I haven’t felt since The Stanley Parable: prodding and poking at the corners of the world, never knowing if you’ve seen everything, hearing whispers of a secret boss, wondering whether you’re treading the same ground or different ground that’s been artfully designed to look like the same ground, that sort of thing. In this age, where everything that isn’t explicitly spelled out can usually be divined by glancing at the achievement list, I have nothing but the utmost respect for a game with the rocks to keep actual, proper, world-shattering secrets under wraps. On the other hand, my inner completionist – don’t try to tell me you don’t have one too – is dying out here. I wouldn’t even have known about persistence between playthroughs if I hadn’t hopped right back in after finishing the first one, and while things are certainly different enough to justify going through again – aside from, you know, it just being an amazing experience that I want to play more than once – is it really out of the question that we try to speed some of the redundant bits up? You can skip past a couple of plot sequences the second time through – not particularly helpful, since I will never not want to experience *********’s **************** – and the disparate fast-travel systems are only really useful for backtracking to very specific locations. How about a run button? I hear that really helped somebody else’s game out.

Undertale is not a game I should have liked. It’s heavily scripted, dominated by text boxes, stuffed with generic sappy ‘power of love’ themes that let you believe you can solve everything with hugs, and only ever gives the player agency when it begrudgingly slides an ‘X or Y’ question under their nose. Its approach to pacifism is to give you a platter of menu options to fumble your way through, its RPG elements are paper-thin, and it’s about as systemically complex as a game of Fifty-Two Pickup. It hinges almost entirely on its ability to force-feed you something imaginative and novel on every other screen, and that’s why its success is so singularly remarkable. People tend to wear out words like ‘charming’ and ‘quirky’ and ‘funny’ in the indie sphere, mostly because almost anything tends to look that way after months of consuming designed-by-committee blockbusters, but Undertale, bless its enormous heart, encapsulates those words so perfectly.

It is, in other words, the real deal.