Interstellaria Review

Take a moment to appreciate the ever-growing loose collection of games that make it their mission to take boring jobs and make them interesting by appending them with “–in space”. Bulk goods transport? No thanks, I never fancied sitting at the helm of a supertanker for three months playing I-spy. But bulk goods transport in space? Dodging pirates and raiders with a cargo hold full of medical supplies bound for a frontier space station? Hell yeah, let me at it. Accountancy? Nah, not interested in handling money that I’m not allowed to spend on Steam sales. Accountancy in space? Dunno about that one either, but Eve Online has half a million subscribers so it must be alright. Senior management in space? Ah, um, hmm. You know what, let’s just put Interstellaria in the spotlight and see if it puts up a convincing case.

From its very beginning, Interstellaria is a game that desperately wants to convince you that it’s an exciting space adventure. As a tiny earthling who dreams of the stars, you are guided through a cutesy tutorial until you land yourself a job doing something inconsequential – I don’t know, scrubbing the toilets – on a spaceship bound for exciting places where you don’t have to worry about overdue rent. It’s all very “seek your fortune”, not so much setting up a conflict to overcome as it is encouraging you to go out there, find one, and shoot it in the face. A series of unfortunate but predictable events leave you stranded on an alien planet trying to get the spacefaring equivalent of a minivan back in the sky, and from there the galaxy is more or less your oyster. As is pretty typical for this vein of open-world space exploration games, the main story is presented as little more than an optional distraction for when you’re done running trade routes and picking fights with space-punks, but given how breathtakingly dull the game would be if you just zipped all the way through it, I’m inclined to think it’s the best way to handle things.

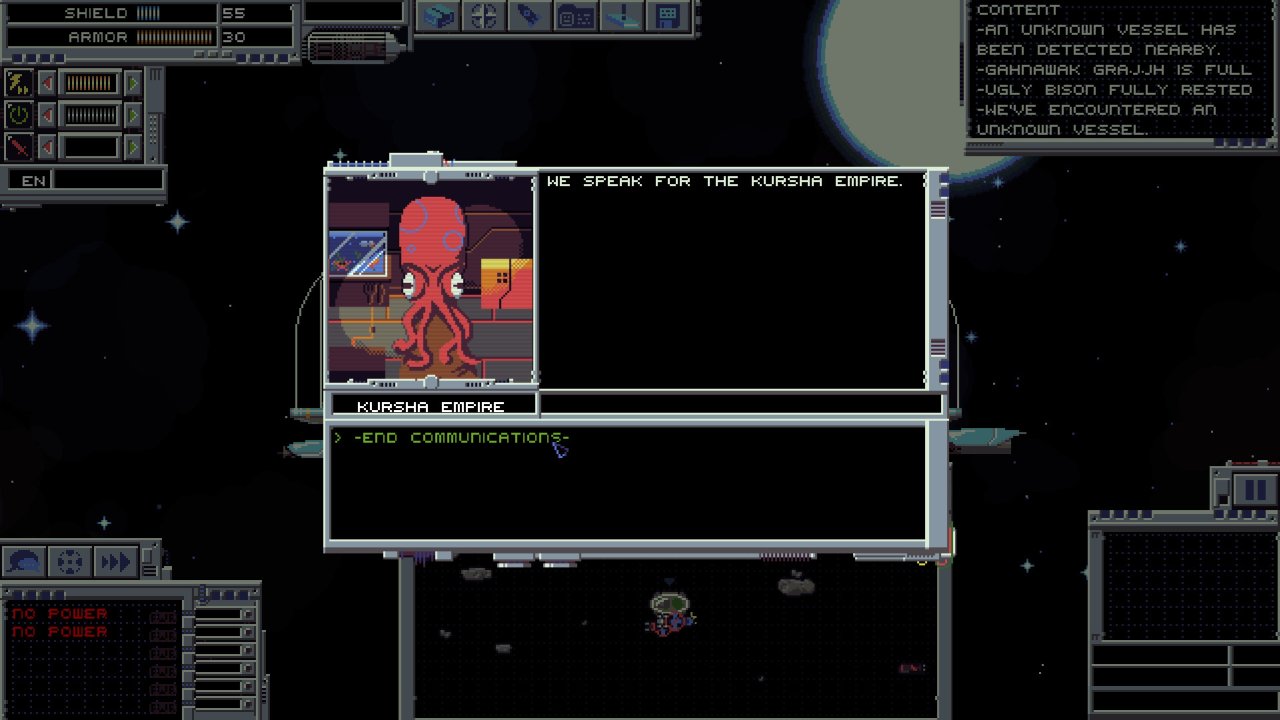

It’s difficult to know where to start with Interstellaria because it doesn’t really have a central mechanic so much as a fractal tree of systems to manage. Broadly speaking, it’s your responsibility to command a fleet of ships across the cosmos and make what you will of it, but that’s about as descriptive as saying that your responsibility in SimCity is to paint a lot of squares with bright primary colours and watch the construction crews roll in. You bought a ship? Great. Now fit it with weapons, navigation, tactical, scanners, medical facilities, stasis tubes, food supplies. Ration out its energy reserves to its primary systems. What, you think you’re going to fly this thing yourself? Get a crew. Feed them. Clothe them. Entertain them. Give them weapons, outfit them with augmentations, assign them to stations. Got into a fight? Alright, time to plot courses, assign targets, toggle weapons. Landed on a planet? Give equipment to your ground team, issue commands, harvest resources, drive back the locals. Keep your cargo hold organised, keep everybody working in shifts, and keep an ear out for trading titbits. Oh, did you forget about the other two ships in your fleet? Hope you set some time aside to keep them in order too.

This is the kind of obsessive, detail-focussed management that you’ll find yourself preoccupied with a lot in Interstellaria; a satisfying brand of micromanagement, reminiscent of city builders and real-time strategy games. There are standards to meet, goals to shoot for, but you have enough wiggle room in how you approach things to make your fleet feel like a product of your own creativity as much as your own work; a carefully-grown bonsai that happens to spew plasma exhaust and 30mm rounds.Maybe you’ll accrue a swarm of cheapo fighters to accompany your bargain-basement corvette, maybe you’ll upgrade to something that lets you be a bit more generous with your energy reserves, or maybe you’ll just weigh it down with the biggest, most ludicrously impractical weaponry you can find. You can even rename your crew if you’re one of those infuriating types who constantly update their friends on the status of their in-game counterparts.

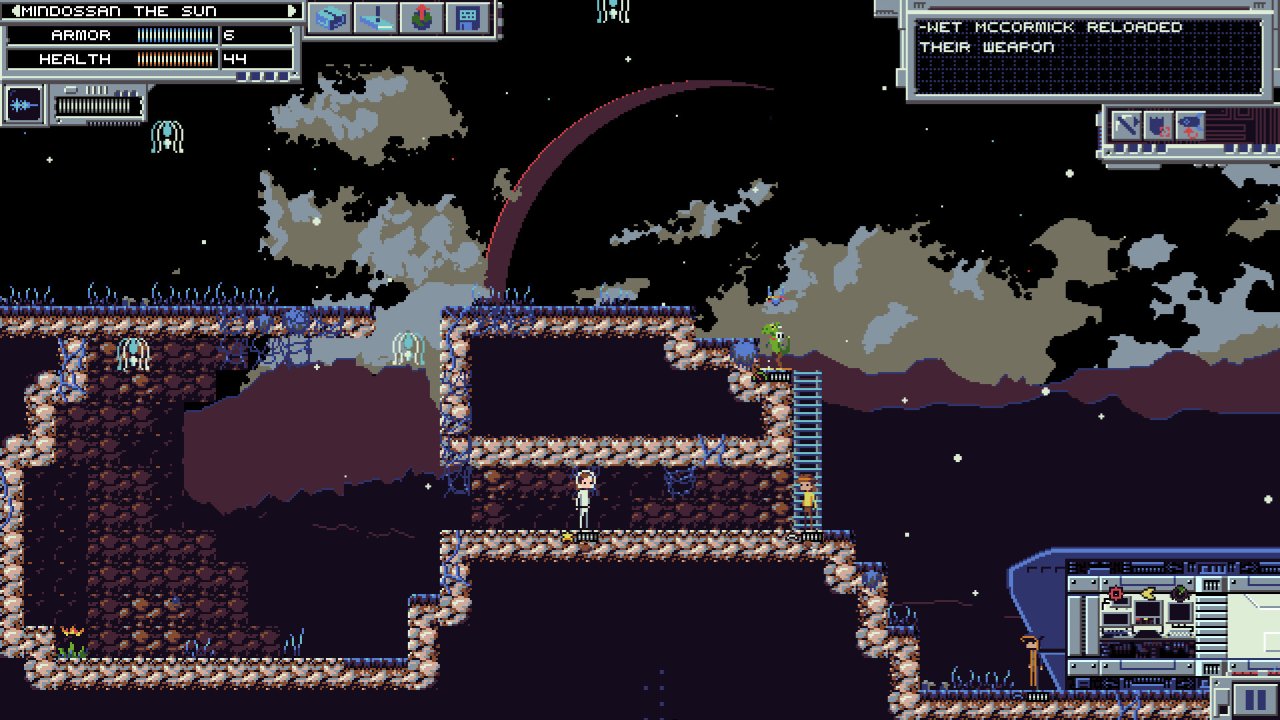

But of course, before you get stuck into any of that, you’re going to need to go out into the galaxy and make some money. Landing on an unexplored planet and getting your crew members to scout out the surface sounds exciting, and the game does have a few cute discoveries here and there to live up to that prospect, but by and large the only things you could possibly accomplish on the ground are trading and resource gathering. The former is simple, if a little needlessly slow when you’re in a hurry – walk around, talk to the right person, engage in capitalism – but the latter is an egregious, time-sucking chore, which really bothers me considering how much Interstellaria actually tries to alleviate that. Crew members can be set to automatically seek out and harvest anything remotely valuable from the surrounding landscape – killing anything that resists, naturally – and there’s a fast-forward button to make everything run a bit quicker, so in theory it’s just a matter of giving orders and sitting back as humanity razes another pristine frontier paradise in the pursuit of wealth.

Now, even if this worked exactly as planned, there’s no escaping the fact that this is the gaming equivalent of watching paint dry, but the thing about paint is that it’s generally not prone to legendarily thick AI that requires your constant, unblinking attention. Most of your time is spent panning back and forth between your various crew members, making sure that their pathfinding isn’t leading them into certain death, or that they aren’t endlessly failing to jump onto a ledge while a pigeon pecks them off, or that they aren’t getting into melee-range scraps with something with teeth bigger than their entire body. They won’t even go back to the ship when all they have left is an empty space-peashooter and a mouthful of broken teeth. I appreciate that you’re still trying to keep me involved in proceedings, Interstellaria, but I’d rather it was through being able to give more fine-tuned orders or doing something else useful while I wait, not playing babysitter to peons so breathtakingly incompetent that you start to wonder what the education system looks like in the distant year of 20XX.

Thankfully, unless you’re chasing the next arbitrary plot advancement device – the full range of which includes a few astoundingly dull fetch-quests – you’re never really required to go through all that. Things look a lot rosier out in the interstellar void, ironically enough. Your ship’s various systems need to be manned in a manner not unlike FTL, but in order to get certain bonuses while at their stations, your crew’s needs also need to be fulfilled in a system that resembles pared-down Sims. Juggling everybody around in shifts to keep everything working smoothly is another weirdly satisfying management job that Interstellaria unloads onto you, and there’s something very humanising about getting your crew to work in shifts during long trips; one driving, one catching a snooze, one fiddling with the radio and one sticking their head out the window. Oddly enough, of all the systems to repurpose from other space exploration games, one thing Interstellaria drops is any kind of fuel system: you can joyride through space for as long and far as you like in any direction, so long as your ship doesn’t end up in a thousand or so pieces after trying to ram an artillery shell. I’m not saying that this is some vital checklist box going unticked, but having that kind of limitation lends thoughtfulness to your navigation, encourages you to plot a course with stopping points that makes the most of the… well, space. As it is, you can pretty much just bring up the map, click wherever you want to go and make a beeline for it, which by comparison is about as engaging as chewing on a damp flannel rag.

That is, until somebody has the poor judgement to get all up in your space-grille. In contrast to combat on the ground, which amounts to little more than bumping your underpaid crew into extraterrestrial wildlife until the latter explodes into coins, Interstellaria’s space combat is probably its freshest feature. In a nutshell, it plays a bit like a slowed-down mouse-driven shmup: you power up weapons, get everybody glued to their respective screens, then plot a rapidly-changing course in an attempt to dodge the incoming hailstorm of bullets, shells, energy spheres and asteroids. Novel idea, potentially very hectic as the stakes rise, but merely kind of okay-ish in practice. For a game about obsessively controlling every tiny detail of your fleet, there’s a lot of fine control missing from Interstellaria’s battles: you can’t set weapons to target different enemies, you can’t choose which ones receive power (except by changing their slots entirely through your ship design screen) and after watching my chief tactical officer miss for the hundredth time because he never played Tribes and doesn’t understand how to lead his shots, I just want to slap him away from the controls and do it myself.

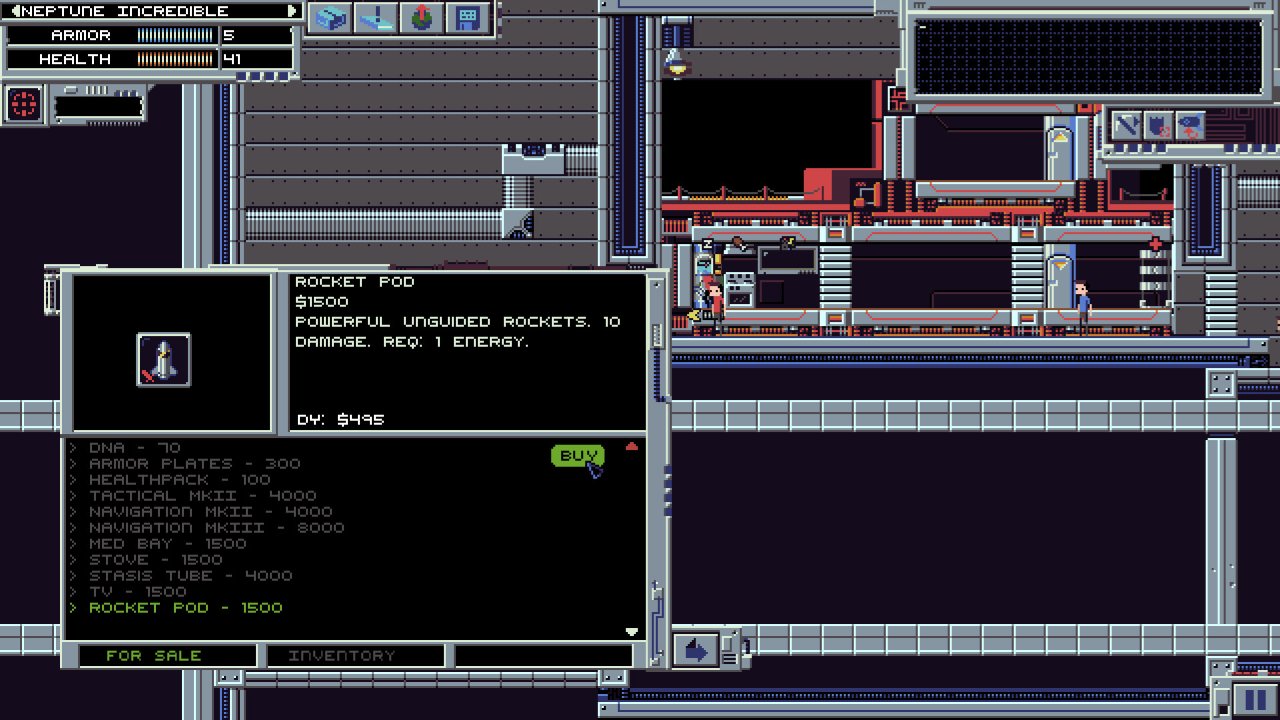

Or maybe he’s actually a crack shot, and he’s just been working with the same controls that I have this whole time. Interstellaria’s interface isn’t terrible, but it does feel old; the kind of gunmetal-grey, screen-covering, largely mouse-driven, inefficient UI that would feel right at home in a late MS-DOS game like System Shock, which I’m guessing was intentional.While wrestling with the UI elements isn’t much of a pain in itself, the ratio of faffing about with windows to actually getting things done is well into the red zone. I can’t just stroll into a store, point out a particle cannon and tell the game which ship to bolt it to; I have to buy it, get everybody on-board, initiate take-off, open up my inventory, move it from my “away” cargo hold to my regular cargo hold – put your hand down, I don’t know what that physically entails either – close the inventory, open up the fleet management window, click on the right ship, scroll through the cargo hold, then drag it onto the right slot. And yet, despite my time being repeatedly wasted, I can’t help wondering if the game would have the same soul if all this was painless. For a game primarily about upper management, it’s strangely appropriate that your biggest adversary is a slightly-obtuse tangle of bureaucratic forms, menus and windows. You could streamline it, sure, but you’d only be cheating me out of gameplay. Like, where does that conclude? A big button in the middle of the screen that you just press to make everything right?

I was being flippant when I wrote ‘biggest adversary’ there, but on reflection it’s a lot closer to the truth than I’d like. Interstellaria feels like the kind of game that would really benefit from being tough as nails, but the only nails it can offer up are made from soggy tissue paper and discarded ice-cream wrappers. Partially this is down to the game’s predilection for putting safety nets everywhere: there’s no enemy on the ground, however imposing, that can’t be defeated by the dishonourable strategy of getting your crew to slowly chip away at their health, run back to the ship’s medical vats for a free heal and ammo refill, jump back into the fray, and repeat as necessary. There’s no damage to your ship that can’t be fixed by parking on the side of the intergalactic highway and getting your engineer to tinker with his lathe for a couple of minutes. Don’t feel like fighting that incoming hostile ship just yet? Cut power to the engines and the whole universe will stop to wait for you. Even when the game finally grows some teeth, it’s too little, too late: by the time enemy ships were heavily armed enough to prevent me from just effortlessly weaving around their attacks, I was already the proud owner of a cruiser strong enough to just plough right through anything short of a planetoid. The only way to really fail is through gross negligence, and even then, falling asleep at the captain’s chair is rarely punished by more than a couple of minutes’ setback.This is the kind of game where you don’t buy better equipment to give yourself a better chance of survival; you do it to make the tedious bits more bearable.

But what really shoots down Interstellaria, more than anything else, is that its universe is about as expansive, deep, and interesting to explore as a set of office cubicles. You can easily joyride from one side of the star-map to the other in a few minutes, and while the game certainly packs a lot of planets into that expanse, most of them just can’t be landed on at all, or offer nothing more than the opportunity to pick more bloody flowers. The whole game feels like a case of getting all dressed up with nowhere to go: you build up a fleet, build up a crew, get everybody prepped for their first day voyaging into the unknown void, and then just sort of scoot back and forth around the galactic neighbourhood, blasting anybody who challenges you into smithereens while chasing plot events with no purpose besides delaying the ending for another few minutes. All that micromanagement I was gushing over so breathlessly on the last page is still great, but it’s all done for its own sake. If you just want to be handed the spacefaring equivalent of a model train set and a lifetime supply of construction glue then Interstellaria can provide, but don’t blame me if the first trip around the kitchen table doesn’t feel like much of an adventure.