Hero of Many Review

In order to be pretentious, you need to be pretending. That little quip keeps popping up in my head when I play through indie titles, because indie games want to appear deep in the same way that triple-A titles want to appear popular. With smaller development cycles and teams to work with, there’s bound to be a healthy dose of Crazy Juice misting around any indie studio, and it should come as no surprise when that slips into the game. Thankfully, my most recently-played indie title, Hero of Many, seems to have escaped from its studio ‘uncrazified’. Mostly.

Many paths, but only one solution

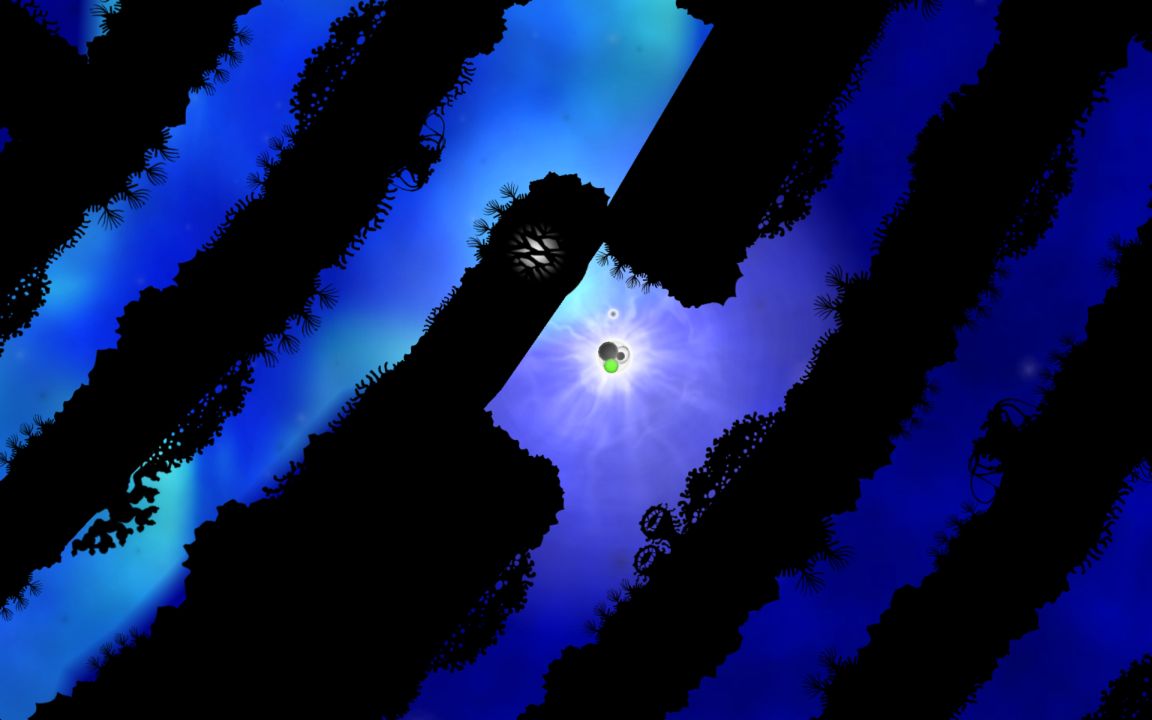

The first time you sit down to play Hero of Many, its influences are instantly obvious. It has that silhouetted aesthetic that’s still rippling out from the big splash made by Limbo, but it also uses a clean, simple color scheme that will remind many-a-player of Thomas Was Alone. Where it differs from both of these is in its gameplay, and especially its core mechanic: gathering and managing a crowd of tiny fish. You play as a… well, as a dot of some kind. Maybe you’re a single-celled organism, maybe you’re a speck of particularly potent food, or maybe you’re a spiritual entity that attracts fish by sheer goodness. Sprinkled throughout every level are swarms of tiny white fish who are attracted to you, following your every ripple. Many of your actions are actually just side-effects of having tiny followers by your side: they’ll eat away barriers and battle enemies in defense of you, their precious glowing glob.

It should come as no surprise that Hero of Many was originally developed for touch-screen surfaces, but while on the one hand this means that the experience has been smoothed over by its earlier iOS release, it’s also true that the controls feel slightly off-base when you’re using an mouse instead of a finger. For example, your main mode of transportation will have you clicking and holding… and holding and holding, to get your blob to move in the right direction. At the beginning of the game, when you’re eager to simply swish blithely through the kelp and crystal gardens, this constant mouse-holding can actually get tiring, but the controls feel better as the game goes further along: when ever quick dash might impale you on a cluster of spikes, you’re much more likely to use tiny clicks and darts, rather than mad dashes that zoom you to the other side of a chamber.

Enclosure is not synonymous with safety

The swarm-based mechanic at the heart of the game isn’t new: it was used on the more kid-friendly Glowfish a few years back, but it’s such a rare form of gameplay that it still hasn’t been given its own genre yet, and it’s easy to see why. Every action in the game is imprecise: you can’t target individual allies or enemies, and the most surgical action you can take in the entire game is the rough equivalent of telling your little tadpoles to “Swim roughly in that direction.” Even your own movement through the landscape is, for lack of a better word, ‘wobbly’. It always feels like you really are submerged underwater, sometimes with currents and eddies that push you around. However, the good news is that the designers of the game have wisely understood how to deal with this unpredictability: the gameplay never relies on precise maneuvers or exact timing. The result is a game that might feel a little too easy for those seeking a challenge …until you lose a few fish to a bad maneuver into some hungry tentacles: then you’ll feel like an idiot.

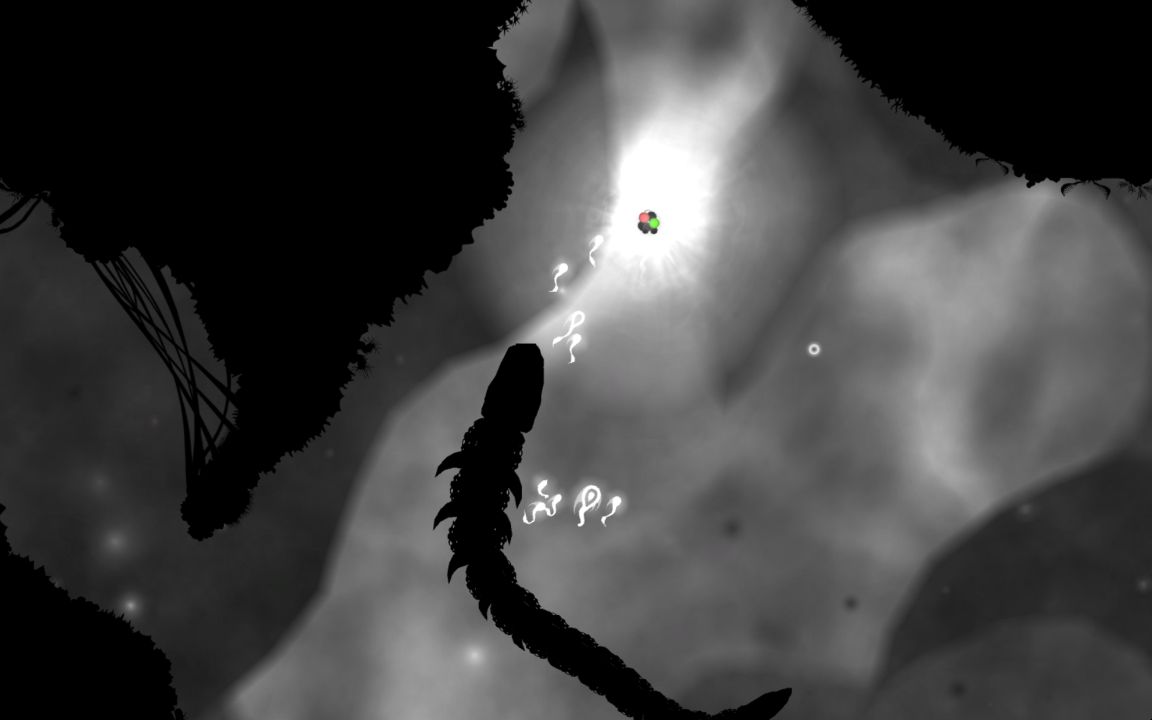

Did I say hungry tentacles? Yes, that’s right: it turns out that the whole world hates you and your tiny cadre of chordates. Spikes, falling rocks, evil black fish (we know they’re evil because they’re all shadowy and such), huge sea-monsters, and other amoeba-gods, like you. They all want to eat you, or stab you, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to try to get through everything without losing one of your precious followers. Your fish are used simultaneously for attack and defense, and with each hit to your glowing body, your ability to attract fish weakens, until you’re left lonely and vulnerable in the harsh world.

The soundscape and music of the game is particularly effective, and you’ll be surprised as you play at how immersive (he he) this underwater world can be. The word that flows in and out of this game is “organic”: the incredible simplicity of controls, the purity of the shapes, the easy division into white and black, all these visuals flow together in a natural way that proves the game has been ironed over until the experience is silky smooth. You’ll always naturally be able to figure out what your next step should be, or what obstacles you should particularly avoid.

Discerning friends from enemies has never been easier

All that I’ve said about the game so far is enough to pass it off as an acceptable way to spend a few hours, but the game actually goes beyond this and includes some wonderful sprinklings of narrative. Nothing ground-breaking: you won’t be following the Epic of Gilgamesh throughout the course of the game, but every level will have some very brief cutscenes incorporated seamlessly into gameplay, just enough to identify good guys and bad guys, and to achieve a sense of progress and building tension. And it’s all done without words of any kind, with colored dots for main characters (again, the comparison to Thomas Was Alone is inevitable, only this title goes one step further). This is the kind of game that I wish could be shown to most start-up game designers so I could point to something and say “See? If this game can build tension and conflict strictly from the movement of their characters, why can’t you do the same thing?”

The main criticisms that can be brought against Hero of Many are the trademarks of the indie scene: the short length, the simplicity of content, the ultra-minimalism, etc. Even at only five or six hours of gameplay, the main mechanics stop just short of getting tiresome, and there really isn’t much replay in the entire experience. That said, the greatest compliment that can be given to the game goes back to that word I was considering at the beginning of the review: ‘pretentious’. Because you see, at the end of the game, the only written text to be found in the entire experience (including all menus), is revealed as your reward for completing the game: a quote from the Tao Te Ching, the East Asian ancient philosophical text. In nearly every other game, this would be pretentious, a cheap attempt at looking deep by referencing classical literature. However, in Hero of Many, the reference to eastern philosophy is nicely interwoven into the entire experience. In other words, Hero of Many isn’t pretending. It’s teaching.