Neon Struct Review

You know what the trouble with cyberpunk is these days? It’s getting too bloody difficult to romanticise. Maybe ‘high-tech, low-life’ was a rad thing to say back when people still thought the world wide web was pretty hot stuff (and would actually drop ‘world wide web’ in casual conversation) but now we’re more or less poised on the edge of the future that cyberpunk fiction embodies, and without the guiding hand of an author, the reality is pretty ugly. Hackers aren’t cool Robin Hood figures who can look good in a trench coat even in the middle of summer; they’re bored teenage sociopaths and soulless white-collar security experts. People are using technology to thwart systematic oppression and censorship right now, but the oppression and censorship aren’t coming from gargantuan megacorporations so nobody really seems interested. Domestic hover-drones are right around the corner, but all they’ll be able to do is deliver the Sailor Moon box-sets you ordered off the internet. Cyberpunk is more relevant than ever, but without its obsession with the urban, the nocturnal, the deviant, the shocking, the colourful and the subversive, the heart just isn’t in it. Well done to Neon Struct, then, which manages to reconcile realistic cyberpunk themes with a cyberpunk setting so retro that it’s a wonder nobody straight-facedly drops the term ‘jack in’.

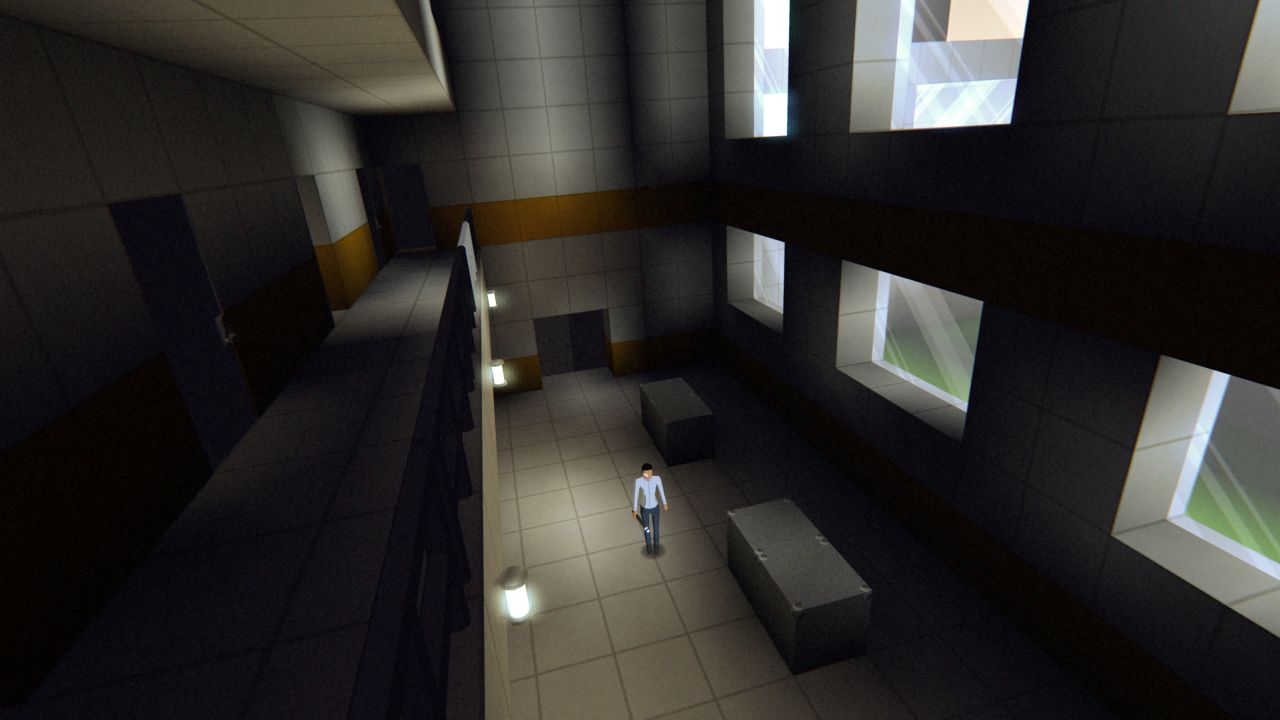

So here’s how that works: you play as federal secret agent-y person Jillian Cleary – oho, another J.C, very clever – in an alternate-future 2015 where there’s a global lightbulb shortage, Google Glass has somehow gained traction (it’s really a security-grade HUD, but whatever) and bright neon signage never went out of style. It’s a bleak, minimalist world of constant surveillance, information control and powers operating beyond the law, surprisingly contemporary themes that the game is happy to explore when Jillian inevitably ends up on the wrong side of pretty much all of them. If the premise of this cyberpunk immersive sim sounds a wee bit familiar, don’t worry: Neon Struct feels more like a personal tale of being on the run than a globe-trotting conspiracy thriller, and the gameplay is considerably more Thief than Deus Ex, focussed on a core set of skills, items, and stealth systems rather than splurging all over the place with augmentations and a full-blown inventory system and such. You get a light meter, a pair of tap-dancing shoes, lots of dingy corners to cower in, and even the sweet slide move that was in Eldritch – made by the same chap, incidentally – though fortunately without the associated ability to bunnyhop past everything and more or less break the game. On the contrary, stealth in Neon Struct feels methodical, rewarding the player who sits back and carefully maps out a plan over the player who wings it and hopes that running across a tiled floor doesn’t bring every guard in the building down on them. Dishonored has catered to my disgusting frothing impatience far too effectively to stop this feeling a wee bit tedious at times, especially when I’m watching an oblivious citizen slowly shuffle across the floor I need to cross for the third or fourth time, but when a game tries so hard to be Thief with every fibre of its being, you can’t help but respect it for capturing the pacing too.

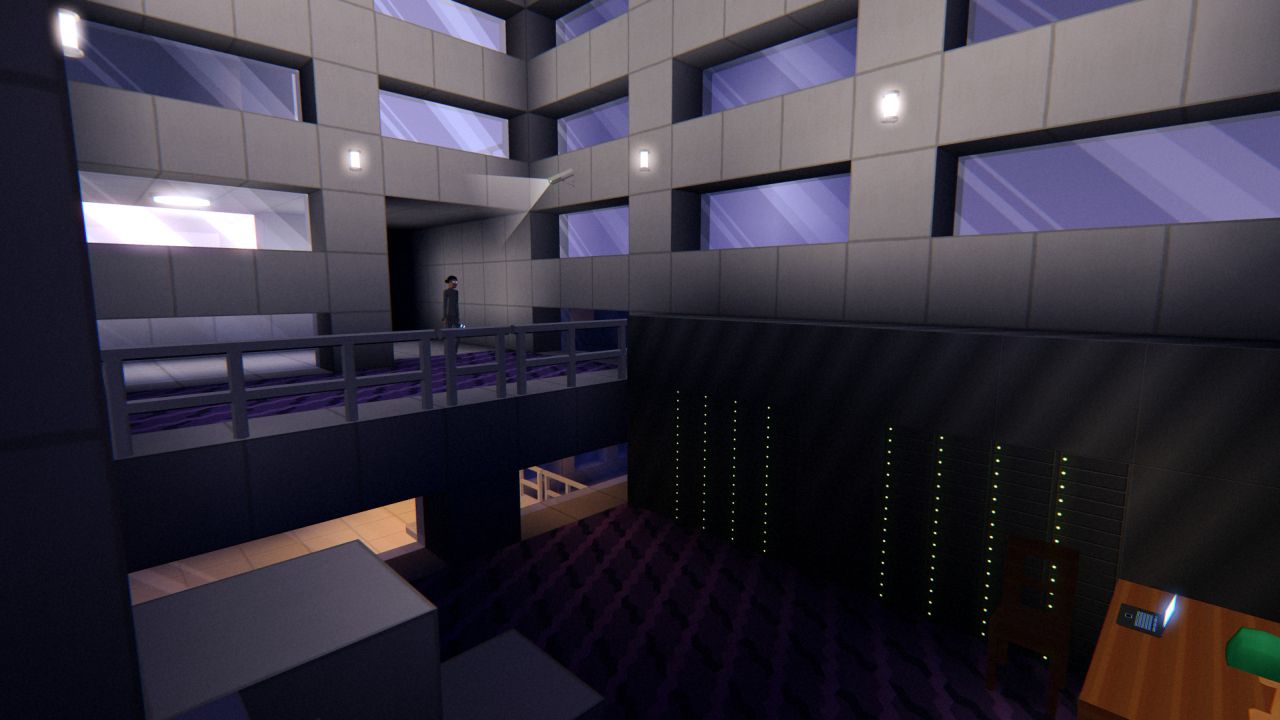

Especially when Neon Struct feels like the first immersive sim in a while to actually get level design more or less on the mark. I’m not going to spend too much time praising it for its non-linearity because let’s face it: that’s the base-line, especially for a Thief-like. What Neon Struct’s levels do well is believable structure; many of them are just buildings, full of rooms without explicit gameplay purpose and innumerable ways to get from anywhere to anywhere else, and while this would spell doom for any kind of scripted experience – nobody wants their daring escape halted when they accidentally stumble into the toilet – it’s the kind of hands-off approach that works swimmingly with something this dynamic. The lack of a map seems like a bit of a poke in the eye, especially for some of the larger sprawling missions, but it does lend itself well to the kind of meandering, opportunistic traversal of levels that more or less characterised my playing style for Thief II. The difference, of course, is that unlike Thief II your primary goal isn’t to walk into a building and walk out again later carrying enough gold to make teeth for every beggar in the land, so obviously loot is no longer your main motivation to poke around in the dark. Instead, exploration is largely rewarded with finding and signing geocaches in obscure corners of the map, which grant you Hitman-esque distraction coins to use on guards. It’s a nice feature that fills the hole left by no longer being able to snatch all the silverware, but aren’t we on the run from a shadowy all-seeing power here? At every twist and turn the game is like “you shouldn’t have chatted with that clerk, now the agency knows your exact location!” and yet Jillian is happy to leave a literal paper trail everywhere she goes. No wonder the future-present is in such a mess if secret agents are this naïve.

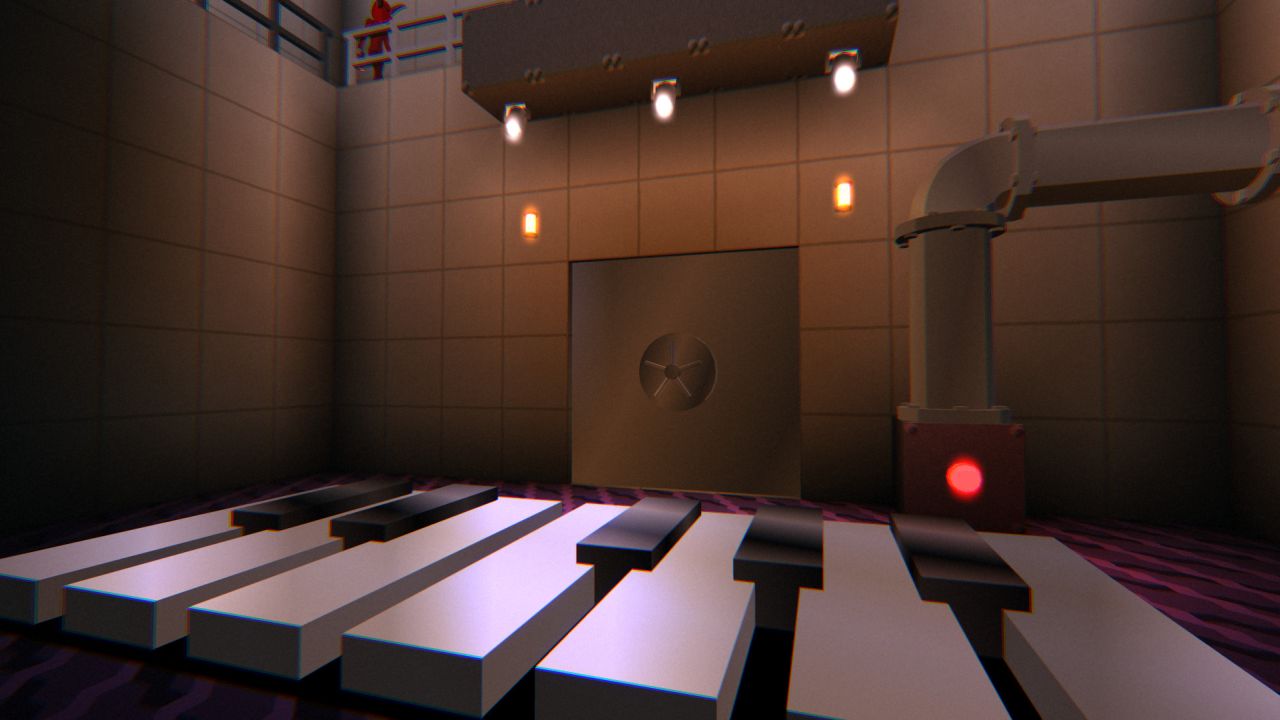

Alright, maybe Jillian is an exception. For the most part, the security you’re going up against is actually fairly reasonable: the AI does the usual boring stealth guard business of patrolling in fixed routes or staring blankly out of windows ad infinitum – I mean, if you lived in a dystopian future, wouldn’t you? – but apart from situations where it’s possible to stymie them by hiding somewhere that’s technically accessible but might as well be on the moon according to their pathfinding, guards are usually pretty good at sussing you out. They’ll even be alerted by lights suddenly going out or doors spontaneously swinging open right in front of them, though sadly I have yet to find an NPC that takes this to mean they’re being haunted by a poltergeist and runs in the opposite direction. I only wish that the levels’ electronic security measures could, uh, measure up to that: some doors need keycards and some need numeric codes, but most of them can just be hacked by bringing up your future-GameBoy and playing a round or two of Breakout, which – while a neat, scalable minigame in its own right – feels a little bit too straightforward at times. You could draw parallels with Thief again, and the way that keys could let you bypass a couple of seconds of panicked lockpicking if you were in a bit of a hurry, but the difference is that Thief was prepared to put down its foot occasionally and say “come back with the bloody key or don’t come back at all”, while Neon Struct feels so terrified of gating the player that it’ll let you bypass just about every barrier with ease. I’m not asking that vital objectives are locked away until I hunt down a code arbitrarily stashed away elsewhere in the level, but when you can get anywhere you want through a combination of five-second minigames and keycards opportunistically pinched from whoever happens to be passing by, nowhere feels especially secure.

What does the world feel like, then? Well, if you’re like me, and were more partial to Deus Ex back when it was moody, dark, and not obsessed with putting yellow cellophane over the camera lens, you’ll eat up Neon Struct’s dimly-lit concrete Brutalist dystopia with glee. Its spaces feel cold, uninviting, often impossibly sparsely furnished, clearly created with utility in mind, and while you could consider that an accidental by-product of there not being much actual detail to work with – five tables and a counter don’t make a restaurant, unless the high-class party trick of the alternate-present is using nanomachines to condense food out of thin air – I’m prepared to give it the benefit of the doubt. Not too sure about using the voxel-y level geometry again though; yes, yes, it kind of fits the imposing concrete-and-glass aesthetic, but without the randomly arranged environments or destructible terrain of Eldritch it does feel a bit unnecessary. Hints of a future level editor have been dropped, though, so maybe it was just a considerate choice to save potential modders from the hair-tearing horrors of vertex editing.

Then again, when it comes to the immersive sim, champion of games that you can sink into like a big, warm, soapy bath, what you hear is as important, if not more, than what you see. Neon Struct’s sound design is, like much of the rest of the game, is a bit on the minimalist side. A lot of thought has clearly gone into it, from the Thief-like policy of amplifying gameplay-relevant sounds over background guff, to the distinct Metal-Gear-Solid-esque beeps that guards make to indicate their alert status, but while it’s nice that the game is doing everything in its power to make its soundscapes nice and readable, at times I feel like it almost goes overboard on this: NPC footsteps travel so far and so effectively, seemingly unaffected by piddling interference like, say, concrete walls, floors, or doors, that sometimes all you can hear is a staccato cacophony of shoes on tiles from everywhere in a thirty metre radius, a sound that I am now certain will play in my own personal hell. Aside from the requisite background white noise that permeates all the good Thief games, there are precious few ambient noises to bring life to the environments, and outside of peaceful zones between missions there isn’t any ambient music either. Eldritch compensated for its papercraft Lovecraft monsters with a catalogue of groans, wails and suspicious bubbling noises, which actually made for some pretty atmospheric skulking around, but Neon Struct might as well be taking place in a series of deathmatch arenas. Some sounds are just missing altogether: the big stompy robots in later levels being audibly indistinguishable from ordinary guards ended up leading to multiple faux pas and at least one “oh, sorry, excuse me” .

Furthermore, as pleasing as it is to see Neon Struct pick up the Thief formula, dust it off and turn it into something fresh, there are a couple of elements I’d rather had remained in The Bonehoard, as it were. Scrolling carefully through the contents of your inventory one at a time, Thief-style, is all very well when you’ve found a nice dark corner to hole up in, but when things get hairy – usually in the exact kind of tight spot that a well-timed gadget might actually help you out of – using the thing you want in a hurry is like trying to operate a Rolodex in a wind tunnel. That’s not to say there aren’t places where the game improves on Thief, though; I like how it bypasses all that ‘lethal or non-lethal’ guff with ambiguous terms like ‘takedown’, leaving it up to your imagination whether that wet thump signifies a guard going home with an egg-sized lump on their head, or a neck that now resembles a stick of chalk in the grip of a P.E teacher.

Let’s polish things off with the story – or at least, what story there is. While the game’s world-building does a pretty good job of getting its issues across – supported by news terminals, NPCs, memos, that sort of thing – the narrative itself is kind of forgettable and strung-together. You spend nearly half the game just on the run, ricocheting between characters with roles as significant as mid-game GTA mission givers without any real goal in mind, and even once you have a distinct overarching objective very little actually occurs. It’s like in Deus Ex where you couldn’t even take the subway to Hell’s Kitchen without being inescapably embroiled in several relatively inconsequential missions; the difference being that Deus Ex was a globe-spanning saga with at least four distinct acts, while Neon Struct is short and sweet enough to be happily polished off in an afternoon. Can’t dawdle when you’re working with that kind of timespan, Jillian.

The ending’s a bit anticlimactic too, mind: you basically just pop up to the local news station, tell the director what you plan to do and what part of your discoveries he ought to publish, and then the credits pretty much roll. It’s a long way from fusing with Helios or plunging the world into a second Dark Age from a bunker deep below Area 51, but perhaps for a more grounded cyberpunk plot it’s more appropriate; the idea that sweeping, radical changes to society happen thanks to the ideas that the media we consume put in our head, not wild heroics happening somewhere off the grid. I can also appreciate the moral choice that the game throws at you right at the end to tie all its issues together – an actual difficult moral choice too, not a big lever with one side marked ‘friend to all living creatures’ and one side marked ‘Konami upper manager’ – but it’s a bit wasted considering that you don’t get to see the results of your actions. Remember how Human Revolution ended with Adam Jensen dryly narrating over a silent documentary and telling you why you’re such a smart cookie for picking the option you picked? Well Neon Struct is more like the end of one of those old movies where they tell you what happened to all the characters five years down the line, except instead of stock footage and actors in slightly unconvincing ageing makeup, you just get a post-credits sequence where you wander around in VR and get text dumps from statues.

Neon Struct is not a revolution by any stretch of the word, but a faint echo of a revolution that we’re still struggling to learn the lessons of. Countless games have built on Thief’s mechanics, elegantly incorporating them into their own systems or simply lashing them to the side with bungee cord, but few have been able to grasp its unmistakeable feel, an intangible quality composed of so many small, subtle features; the sound design, the pacing, the tension of involuntarily sucking in your gut as a guard patrols inches past your face. Neon Struct doesn’t master that feel either, but it comes closer than any game I know.

In short, it’s a minimalist Looking Glass game, and if that’s not praise then I don’t know what is.