The Bridge Review

Woe unto the video game Johnny-come-latelies. They arrive at the tail end of a zeitgeist, soliciting comparison with the forerunners from which they liberally borrow. Consider, say, the plague of “edgy” mascot platformers that beset the 90’s, or the catalogue of “Not-quite Call of Duties” available today. The independent development scene is currently facing such a glut: one of artsy puzzle platformers eager to mimic the successes of games like Braid and Limbo. There’s nothing inherently wrong with usage of strong precedent, but many games end up diminished by unflattering comparison to the genre’s best. The Bridge is one such game, and it’s apparent in the first minute with its glassy-eyed professor lead.

The camera descends to reveal our hero, in all his tweed glory, snoring beneath an apple tree. A prompt bids you press left, then right, and the world rotates in turn. The motion shakes a few apples from the tree, introducing the second mechanic at play in true Newtonian fashion. It’s a short walk to the right to a simple house. Once inside, the near wall disappears to reveal the interior and a numbered door. Entering that door uncovers another set of numbered doorways, each leading to their own level. A nearby pedestal displays some plot-related text, a cryptic morsel of exposition.

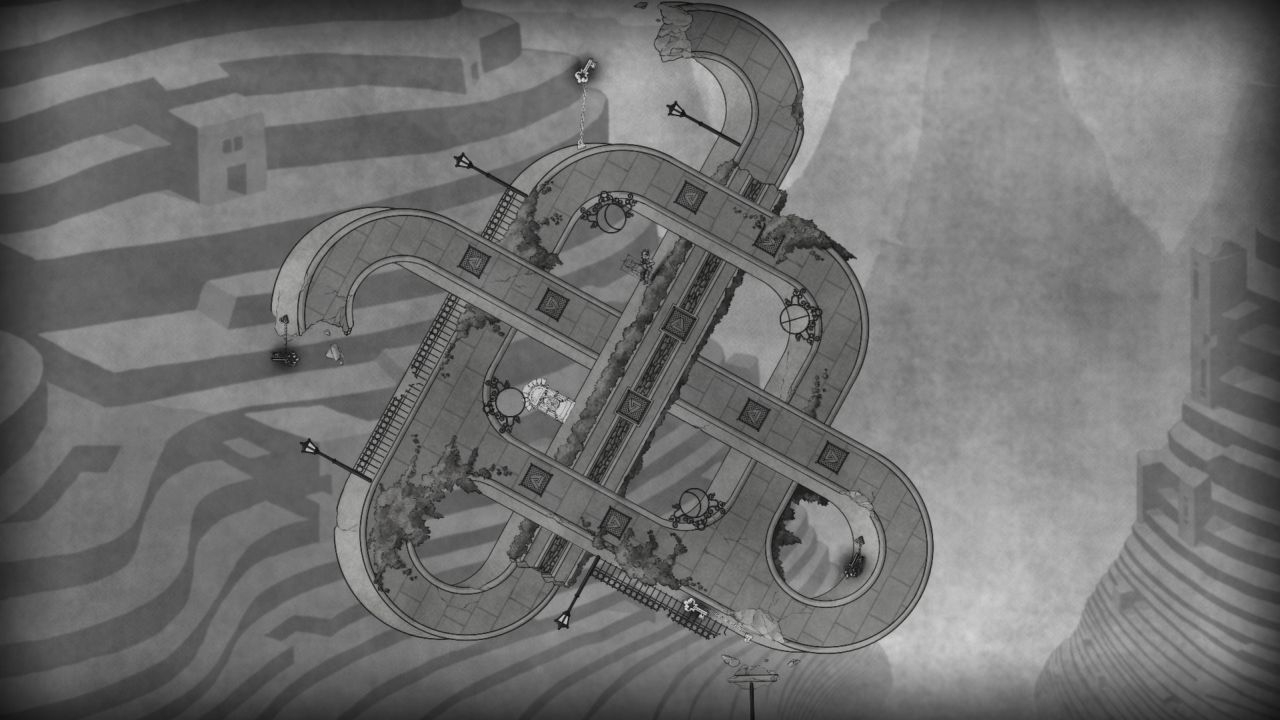

It’s Braid, essentially, save the greyscale pencil-sketch aesthetic. The Bridge dips so deep into the well of Jonathan Blow’s indie sensation that it often feels less a homage than an outright retread. And that’s before we get to the time-rewinding mechanic. Mercifully, there’s also a less conventional bit of precedent at work in The Bridge: the works of M.C. Escher. Each door leads to a unique floating structure akin to the impossible objects so inseparable from the Dutch artist. They’re a sight to behold: warped, otherworldly contraptions that wed earth and architecture to the sort of brain teaser tchotchkes your least favorite grandparent likes to give as a holiday gift. The graphite aesthetic lends them a melancholy severity that’s complemented by the game’s brooding soundtrack. Key objects flicker and shift like images in a flipbook. The nameless professor is quite literally sketched into place within the structure, and must reach an exit door in order to proceed on.

Those doors are often placed tantalizingly out of reach, as are the keys and switches sometimes required to unlock them. The Professor can walk about, but can’t jump or scale the environment, and there’s often an impasse or two between him and his goal. At first glance, there’s typically no visible means of reaching one’s objective. Recalling the ability to rotate the world, one turns the stages about their center, shifting the effect of gravity so that walls become floors, then ceilings, then floors again.

The first level of The Bridge demonstrates this quite succinctly. The door to be reached sits at an upper floor, but there are no stairs in sight. After rotating the stage, however, a column becomes a new platform, and the divider between what were once segregated floors can be traversed. It’s all possible through some clever optical trickery: the visuals in the level play fast and loose with the laws of perspective, distorting the sense of depth.

It’s a promising start, but sadly, The Bridge goes on to eschew its unique aspects in favor of well-trod ground. Escher’s influence quickly gets relegated to cosmetic duties, while the more rote, limited gravity-based physics system does all the heavy lifting. This results in a systemic problem: the game feels held back by its chosen methods of interaction. The character’s single-axis movement and the rotation of the levels are really the only two variables under the player’s control, and each is binary. Left or right, clockwise or counter-clockwise…there are only so many possibilities that can result. A great many of the stages, consequently, can be beaten by simply spinning the environment arbitrarily as you wander about. Sure, there’s some novelty to walking on ceilings. But this transition happens through the lazy spin of the level that you orchestrate, so there’s no dizzying sense of displacement here. Just slowly walking, slowly falling, slowly being crushed by the odd boulder.

Indeed, there are a great many boulders crashing about within The Bridge’s floating puzzles. There are also vortices that draw in nearby matter, sliding doors, and other items from video games of yore. They’re a bid for variety, but alas, two of the five levels in each world are expended teaching their ins and outs through basic tutorials, so there’s not much room for them to develop. Nor do these introduced objects seem to have anything to do with the game’s overarching narrative. There’s no explanation for, say, a vortex to suddenly make an appearance in The Bridge, nor a veil that suspends the protagonist while the rest of the stage rotates. Consequently, they feel like arbitrary, lazy uses of video game convention. Herein lies a problem that The Bridge exacerbates by its invocation of Braid, a game that wove each of its iterative mechanics into its plot and motif far more effectively.

Fall victim to one of those hazards, or otherwise render the level unbeatable, and you’ll need to rely on another Braid staple: rewinding time. It’s not typically necessary; most of the game’s levels are short enough that it’s actually quicker to restart than to wait for the rewind mechanic’s slow acceleration. On the few occasions when it proves useful, it’s because some finicky bit of interaction is difficult to properly execute. One might find, for example, that it’s difficult to get the professor to fall at an exacting angle necessary to avoid an obstacle, or for a rolling boulder to have the proper amount of momentum required to trigger a switch. On such occasions, success comes only at the end of a tiresome loop of rewinds, minor adjustments, and hairline failures. Such repetitious defeats can even make one wonder if they’ve taken the wrong tack entirely – there’s a real potent frustration in arriving at the solution but being unable to perform it to the game’s stringent standards.

The Bridge simply doesn’t confer the exacting controls required to perform its feats of physics. The professor’s a far cry from agile, and any small degree of rotation is bound to send him stumbling down the plane of decline (with an annoying “shuffling” sound effect, to boot). The trajectory of his falls is difficult to gauge. He’s unable to fight against the pull of vortices that draw him in at unfathomable distances. Such issues are annoyances in the main campaign, and outright headache-inducing during an extra set of bonus levels that are unlocked after its completion. In these altered versions of the regular levels, a greater number of hazards are introduced, and dexterity and momentum take on a greater role in successful level completion. In other words, the things that The Bridge is worst at come to the fore. There’s more challenge to be had here at least, even if much of the adversity is ill-gained.

I’d have hoped for the difficulty of The Bridge’s puzzles to derive more from play on perspective than from niggling physics. For all the depth and mystery of the levels, it’s a tremendous disappointment that your primary method of interacting with them is to simply rotate them and walk about on their profile. I wanted to pick at them, to move their pieces, to ascend their crooked ladders and stairways, to walk into the sideways doors and come out in another location upside-down. You do little of that sort in The Bridge, unfortunately. The bizarre accoutrements that line the levels turn out to be largely decorative, and making sense of the traversable portions of each stage isn’t nearly as taxing as one might expect given the source material. More’s the pity – there’s a lot to love about The Bridge’s look, but it doesn’t have much bearing on mechanics or plot.

Lip service is paid to an overarching narrative (something about an assistant and a death), but there’s almost nothing to work with. There’s but a scant bit of text to prop up The Bridge’s story between stages, and it’s so vague as to be meaningless. That it’s included at all seems to just be a nod towards genre convention; indie puzzle games are expected to allude to deeper meaning, and so the game puts on its high-falutin’ airs. But the effort isn’t earnest, and like much else in The Bridge, it doesn’t command interest. It’s content to pose a few contrived questions about perception and infinity, then abandon them to wander off in search of the next rolling ball puzzle.