The Talos Principle Review

Poignant puzzler peacefully ponders philosophy, purpose, and pressure plates

A distinct, unshakeable sense of unease hung over me as I played my way through The Talos Principle. It wasn't the fault of the game, at least not in the conventional sense, and it was far too meta for my brain to accept the possibility that it was intentional. Storytelling? Gameplay? No, despite their efforts to pry open my head and pour in some cold, fresh ideas, they weren't the source. It was Serious Engine 3. As I wandered – or more often, bunny-hopped – through the game's myriad of peaceful gardens, ancient temples and crumbling ruins, I just couldn't shake the feeling – even in such a quiet, contemplative setting – that around the next corner waited a minigun, a horde of headless screaming kamikaze bombers, and a bombastic musical cue or two. Croteam's famous FPS series has been their only notable product for so long that I – and, I suspect, many others – had just assumed it was all they were capable of, and all that their engine would ever be used for. This, then, is my public apology for doubting you, Croteam. I'd send you a cake or something, but considering the number of insufferable comparisons I've seen between The Talos Principle and Portal, you might take that the wrong way.

Oh, I suppose the parallels are there if you really want to look for them. You wake up in an unfamiliar place, solve various first-person puzzles designed to 'test' you at the behest of an unseen voice of questionable allegiance, gradually build suspicions about them, work out what's going on with the help of various clues in your environment, and generally enjoy the pleasant sense that somebody is standing behind you, rubbing your temples with two lumps of cotton wool. Where Portal garbed itself in gallows humour, though, The Talos Principle turns up dressed for a night at the opera. This is a serious, sombre game. Not the usual melodramatic kind of video game seriousness either, 'cause that's at least kind of fun to take the piss out of; this is philosophical sci-fi so high-brow that it's in danger of sustaining a concussion from the tops of doorways.

What I find really elegant about The Talos Principle is how well the opening sequence – brief and simple though it is – communicates what the game is about. The absolute first thing you see in the game is your own robotic arm, shielding you from the sun's rays as you lie in a sun-bleached ruin. You are a machine, supposedly no more alive than Talkie Toaster, and yet you perform a gesture that serves you no practical purpose whatsoever. Are you sentient, then? Do you think and behave as a human would, or merely provide a perfect illusion of such behaviour? If so, surely it no longer matters. Then there's this voice in the clouds, calling himself Elohim, claiming to be your divine creator, and promising you immortality if you complete a multitude of trials. But what could a machine want with eternal life? Again, you show instincts of self-preservation, a wholly biological trait, simply by implicitly accepting his offer. Such is the premise at the centre of The Talos Principle: you are a machine that walks like a man. What does this mean for you? What should you do with your life? Do you follow your assigned purpose? And on a more chilling note... where are all the people?

At first, the story can seem more than a little fragmented. Indeed, between the game's beautiful environments, peaceful music, heavy-handed religious allegory and penchant for throwing seemingly irrelevant scraps of literature at you, it's initially hard not to see The Talos Principle as a game struggling to forcibly pump as many jumbled ideas into the player's head as possible, hoping that enough of them rattle around in there to make it appear all clever and grown-up. Over time, though, the storytelling coalesces into something infinitely more meaningful. Not content with merely posing vague philosophical questions to the ether, the game introduces a character of sorts named Milton, whose purpose is solely to grab you by the scruff of the neck and yell them in your face – figuratively, that is. “What do you think, player? Why do you think that? Have you any idea how inconsistent your ideologies are, you uncultured sack of meat?” An image forms out of a thousand scattered jigsaw pieces – not complete until the very end, but complete enough to let you glimpse the terrible truth, like a hanging bathrobe seen out of the corner of your eye at four in the morning. What initially looks like little more than a clever little puzzler with a bit of pretentious flair thrown in for good measure reveals itself as a genuinely really well-written work of sci-fi. Any game could copy-paste the big questions from the Philosophy 101 course outline and earn a few points from the arty crowd, but The Talos Principle uses its ideas to drive the plot, shape the characters, and ultimately begin to steer your own actions. I dare-say that to people who actually know their Pythagoreanism from their Platonism it probably seems all a bit old-hat, but to totally uninformed idiots like me it's jolly exciting.

It'd just be nice if the exposition was presented as well as it is written. The Talos Principle is a graduate of what I like to call the System Shock 2 school of storytelling: audio logs, text dumps, ghostly apparitions, and let's not forget, an authoritative figure constantly watching over you and occasionally loudly commenting on your progress. It's a good system when your game universe extends well beyond the bounds of what the player is actually doing – as is the case here – but I'm not convinced it's the perfect fit for The Talos Principle. Every puzzle hub has a computer terminal containing a nice varied collection of documents – book extracts, emails, announcements, blog posts from your xenophobic uncle – and while I'll ravenously consume reams of sci-fi flavour text without complaint, it does mean that the storytelling and gameplay have to work in separate rooms to a certain extent, communicating via notes thrown over the wall. There's no sense that the two are integrated or anything; the terminals are just sloppy plot dumps, to be occasionally upended over you like buckets of kitchen swill. Except it's nice swill, I guess.

Oh yeah, there are puzzles. They're pretty good too.

Alright, alright. Elohim is evidently not the most extravagant of deities – as if that wasn't already apparent from the non-biological nature of his solitary subject– since his trials focus less on the whole 'slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra' thing and more on just completing puzzles. Each puzzle grants you a 'sigil', essentially a big three-dimensional Tetris piece that progresses the story: green ones help unlock new worlds, yellows help unlock new puzzle elements, reds – when collected in their entirety – let you finish the story. Technically the game is pretty non-linear, but unless you're the kind of person who intentionally scribbles in the bits of forms labelled 'DO NOT WRITE IN THIS SPACE', you're probably going to end up starting at level A-1 and going from there.

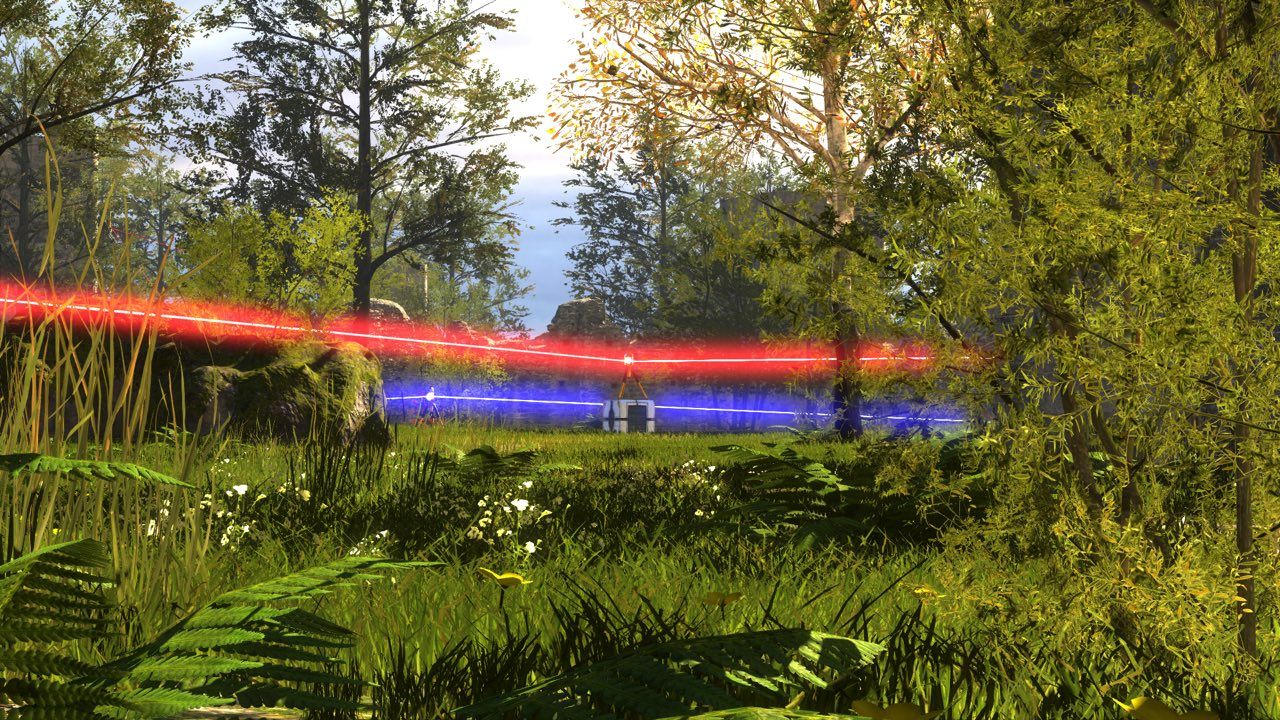

And what a journey you're in for. Strictly speaking there are few (if any) puzzle elements in The Talos Principle that other first-person puzzlers haven't already laid claim to - cubes, buttons, lasers - but I can't think of any that have used them quite so inventively without running out of steam. By my estimate there are around four squintillion puzzles in The Talos Principle, and while it can certainly get a little bit draining towards the end – really, it's a bloody long game – it's impressive how few of them feel like cop-outs. Some work iteratively, giving you a meagre set of tools and providing an ever-mounting set of obstacles as you gain access to more options, while others force you to work economically, using what appear to be an insufficient number of items by cutting as many corners as possible. Others just play with the existing mechanics in new and unexpected ways. They're the kind of puzzles that demand you be completely aware of your surroundings, and even in the small details you can see the game gently pushing you towards this state: the way your goal, the sigil, is always clearly visible to any casual observer, and the way metal grates in the walls are used extensively to let you see the puzzle layout without just letting you run amok.

What I find a bit strange about The Talos Principle's puzzles, though, is that they don't really seem to have a central mechanic. Spatial awareness is all very well, but normally these games have some kind of device – be it the Magtech glove, the Portal gun (sorry), or that cube drawing thing from Antichamber – to provide a fresh perspective. In The Talos Principle, you are, for all intents and purposes, a removals man: pick something up, walk over there, put it down, scratch your robotic bum while wondering if that was the right place to put it. All the elements only relate to one another, with you just running back and forth in the middle getting your daily squats in. I suppose you'd call it a tad unfocussed, though it feels just as satisfying when you finally get your giant coloured tetromino anyway, so I don't know why I brought it up.

Certainly not when there are perfectly legitimate things to gripe about, that is. The Talos Principle's non-linearity – wherein you can visit puzzles in more or less any order, barring those currently locked because you don't have enough sigils – is something that's kept me up for several nights, staring in despair at the ceiling as I wonder what to make of it. On one hand, the inability to skip especially devious puzzles and come back to them later would make progress agonisingly slow, but on the other hand, the lack of a distinct order means that the difficulty curve looks like a sheet of paper that my printer just decided wasn't properly inserted. Even if you play through everything as close to sequentially as possible, the game is somewhat poor at introducing new mechanics and elements, often throwing you straight into the deep end with only the most cursory hints as to what the strange new item before you is actually capable of. It's nice that you aren't just beaten over the head with an obnoxiously descriptive dialogue box – frankly, I can think of nothing that would ruin the atmosphere quite so effectively – but floundering around hopelessly because the game is asking you to solve the fox-chicken-grain puzzle when you've only just been introduced to the concept of boats isn't fun either.

Then you have the sigil locks, which seem to only have been included because somebody decided that the connection between completing puzzles and unlocking progress wasn't quite tangible enough. You know how doors in Super Mario 64 would only open after you'd amassed a certain number of stars? Sure. It was a dubious method of home security, but it worked. Now imagine those stars were Tetris pieces that needed to be arranged in a grid before you could proceed, and you more or less have The Talos Principle's approach to gating progress. I'm not going to get too narky about these puzzles, mostly because they turn up about as often as a dental appointment and don't take half as long, but there's no real satisfaction in solving them either; they're just a thing that gets in your way until you've thoughtlessly fiddled around enough to find the right combination. There's no moment of epiphany when you unravel the solution like the regular puzzles, nor any sense that you're ever building a strategy; you just keep aimlessly rearranging pieces until they finally fit together. It's like the video game block-sliding puzzle has a long-lost cousin that's only marginally less annoying.

Let's return to the story, since there's certainly no shortage of discussion points there. Actually, that's sort of a problem in itself: The Talos Principle's shotgun approach to philosophical discourse, though exciting at first, quickly becomes really difficult to keep track of. There's an in-game journal that aggregates all the terminal documents you read, but what it doesn't keep track of are all the conversations you hold with Milton via the terminals themselves, or all the booming declarations made by Elohim, both of which pretty much comprise the entirety of the plot development. Every time Milton asked a question and the options unfolded, I started to silently beg for a button that simply said “I'm sorry, what were we talking about again?” Failing that, I wished the game would start providing answers that didn't obviously force me towards a predetermined conclusion. Remember G-Man's little speech at the end of Half-Life 2? “Rather than offer you the illusion of free choice, I will take the liberty of choo-sing for you.” If only The Talos Principle could be so above board about its intentions to funnel you where it pleases. It's not the mere existence of a loaded question that bothers me so much as the fact that it gets presented as a meaningful debate, putting you up on stage just so the game can invite everybody to point and laugh at your pathetic response. Then again, the broad range of responses to a big question like “How do you gauge the value of a human being?” probably makes simulating reasonable conversations more or less impossible. Maybe it's a big statement on determinism. Maybe I'm just bitter that I can't make that nihilist computer love me.

Still, if I was to spend time contemplating those conundrums – and other, more earthly questions, like “why is there a fire axe in this temple?” – there are few locales I'd rather gaze upon than those provided by The Talos Principle. You have the snowy wasteland of the hub, the Mediterranean world, the Medieval world and the sandy Serious Sam desert world – which, of course, did nothing to dispel my earlier unease – all of which have been polished to an almost overbearingly peaceful state. The high-tech puzzle elements are totally anachronistic, naturally, but it works in the game's favour, creating environments that feel unreal without falling back on the abstract mainstays: colourful skyboxes, stuff floating in the air for no reason, and half-destroyed buildings sitting in the void like they had all the gravity exploded out of them. After all, the life of a shiny new piece of technology in a decaying world is at the centre of The Talos Principle, so having your surroundings reflect that seems only appropriate. The symbolism is about as subtle as the Kool-Aid Man bursting through a wall made of bubble wrap – heck, Elohim is literally the Hebrew word for 'god' – but the story is so much more than a simple allegory that it seems petty to complain.

All things considered, though, my reserves of pettiness have been utterly exhausted by The Talos Principle. It's a game of exceptional writing and consistently imaginative puzzle design, and while the marriage between the two is in dire need of more communication, they're both individually good enough to lift the game to success. More than that, it's another sure-fire sign that games are still steadily growing up. Not just because it attempts to tackle questions bigger than “how do I ensure that this cyberdemon's internal organs land in at least four different shires at once?” – of course, it is far from the first – but because it so cleverly weaves its ideas into the story in a way that few games could claim to do. Such was the nature of the game's crowning moment, when I watched the last line of credits roll off-screen and allowed one measly thought to work its way through my slightly dazed brain.

“I am going to read so many Wikipedia articles.”

Comments

Comments