Child of Light Review

Away with the Faeries

It’s hard not to fall immediately in love with Child of Light’s achingly beautiful, hand drawn visuals – unless you’re a cold-hearted old miser like Ebenezer Scrooge that is – but Ubisoft’s ambitious and unexpected RPG is much more than it first appears, and also, in some ways, much less.

First the good: Child of Light is an artistic triumph, a download-only, turn based JRPG with all the hallmarks and tropes of a well-produced indie, but instead created by the juggernaut powerhouse, Ubisoft, usually responsible for the likes of the Assassins Creed and Far Cry series.

If that doesn’t quite scan right, that’s, well, because it shouldn’t, or rather it doesn’t. Child of Light is a bold and interesting step in the right direction for a company like Ubisoft, not necessarily as their main focus, but as a side project to fill out their portfolio. This isn’t the first time they’ve explored this territory, though, having recently created or published indie titles such as From Dust, Scott Pilgrim and Child of Eden. But Child of Light feels like something more, pushing further in that same direction. And I hope it continues. What if more blockbuster companies made exciting, quirky and innovative games that didn’t feel like they’d been focus group tested by trigger-happy 13-year-olds and frat dudes?

Child of Light feels like pure expression from its creators. This was clearly made by people who loved the project they were creating. And helming it all we have director Patrick Plourde and writer Jeffrey Yohalem, the double act from 2012’s explosive Far Cry 3 – when talking about change of pace, or following something up differently, Child of Light is about as far away from Far Cry 3 as you can get, and I can’t wait to see what these guys do next.

Child of Light’s protagonist, Aurora, is a princess from 1895 Austria. She loves and is loved by her father, and has a stepmother – yep, you see what’s going on already – but falls ill and finds herself passing into the mythical world of Lemuria, a fairytale setting where the sun, moon and stars have been stolen by the Black Queen. And so an adventure begins.

The story, unfortunately, after a familiar but promising start, turns out to be one of the weakest aspects of Child of Light, as it seems simply content to follow the well-worn tropes of the fairytale, and not subvert them or change them in any interesting or dynamic ways, besides having a predominantly female cast (which is great, but not enough to make the story all that compelling). Which is a shame, given the fact that the characters and the writing have had so much love put into them, trying to create this sad and beautiful world that wants to say something, but ultimately doesn’t.

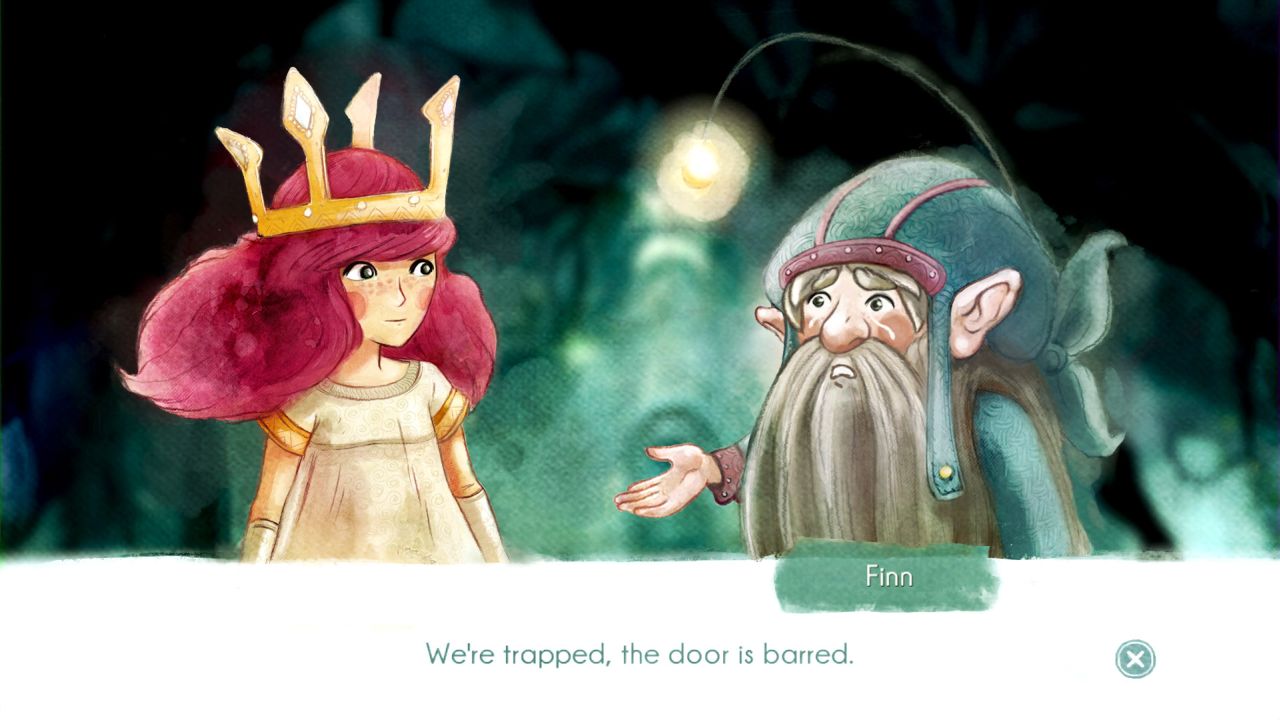

Still, I was more than ready to explore every corner of this 2D, hand-painted setting, which led me from gloomy forests to ancient ruins, cliff top villages and beyond. Every new area is an absolute joy to uncover. Made on the fantastic Ubi Art engine that the last two Rayman games were built on, Child of Light is, at least for the moment, the pinnacle of how good a 2D game can look. If you’re at all into this aesthetic, I think you’ll be floored. The detail in certain scenes, even in side characters’ houses, is so well thought out. I constantly found myself gawking.

But there’s more to Lemuria than looks, of course; the exploration, too, is paced well, if a little familiar. The world is littered with trinkets and items to help with survival, such as potions and spells, as well as oculi – the gemstones used to craft and give passive powers to your party – hidden within coffers and chests. This all works in a pretty standard JRPG fashion, and I found myself exploring for the sake of it – and to see more of the world! – than for any more compelling reason. Oculi are somewhat interesting in that they can be used to craft stones that, say, give resistance to fire, or imbue your sword with light magic, and there’s strategy in changing these up on the fly depending on what area you’re in, but it’s pretty surface really. I feel that it perhaps needed to be deeper or else left out completely.

There’s a light skill tree system too. Every time you level up you get a skill point which can be used to grant you a new move in battle or a passive bonus. There are three trees per character, but they’re all linear and so there’s not too much choice. Again, this is an interesting distraction, and something you’ll need to do to get the most out of your characters, but it could have been executed with a wider range of variety to make it more compelling.

And speaking of characters, just as in every great JRPG, your party grows over time. And they’re a lovable bunch indeed, ranging from a cowardly, bearded dwarf, a circus performer who has trouble rhyming in the games’ ambitious rhyme scheme – more on that in a bit – to a mouse skilled in archery.

Breaking up your exploration of the lush plains of Lemuria is the exciting battle system, which commences when you come across enemies (which you can avoid or attack as you see fit). And so, before long you’ll be buffing and debuffing with each of your party, casting spells and slashing beasts.

And despite everything else, if I’m honest, it was Child of Light’s combat that kept me coming back. In many ways, it’s your traditional turn-based action, but the designers have craftily borrowed the main gimmick of the Grandia series, where an Active Time Battle bar is shown at the bottom of the screen. Icons for both your characters and the enemies move along the bar at all times during battle, from left to right. Three quarters of this bar show the time when you can do nothing, and only in the final quarter, known as the cast zone, is when you can instigate your move. The strategy comes in the form of you sidekick firefly, Igniculus, who you can control to slow enemies down, manipulating when you or your foes will cast next. If you and an enemy are both in the cast zone, but you attack first (i.e. get to the very end of the bar before them) not only will you attack, but you’ll also interrupt them, sending them back down the bar without having a turn. This is great fun, and meant I had to think two moves ahead at all times – however, enemies can also do the same to you, so it’s vital to stay alert.

On normal difficulty, most battles where quite easy, but it’s commendable that they always felt intense and rewarding, and in my opinion that’s a perfect mix. The characters in your party also level up equally even when not being used, allowing experimentation throughout the entire game without penalizing you with a weak, unused character. Sensible save points before bosses and the like go a long way too. This is a clean, modern take on the classic RPG formula.

Igniculus is your firefly companion who can be used to light the way or manipulate objects out of reach. In solo play, at least on Wii U, Igniculus can be controlled with the stylus on the gamepad, allowing for quick, precise targeting of enemies and the glowing orb ‘wishes’ that replenish your health and magic points. He can also be controlled by a co-op partner, which is fun, but not essential. However, arguing in battle with a buddy as to which enemy they should be slowing down and when does change up both your strategy and the way the game feels.

As mentioned before, the story is not the strongest aspect of Child of Light, but it is presented in a unique and frankly rather crazy way. The entire game – that is to say, cut scenes, narration, hidden notes known as ‘confessions’ and even the characters’ dialogue – is all presented in rhyme, and Shakespearean iambic pentameter at that! It’s an incredibly ambitious and commendable thing for writer Yohalem to even try, much in the vein of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic ballad, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. At times it managed to come across as light and poetic in meaningful ways, but unfortunately more often than not I found it got in the way, restricted the narrative, and actually distanced me from the characters and the games’ story. I wonder if maybe just the narrator, or one character could have spoken in this way for more important moments, freeing up regular speech and character interaction for something more accessible and less restricting. Either way, it’s an interesting and new element that Child of Light tackles, and I’d rather experimentation than something completely stale.

The games’ soundtrack, although soothing and calming in a bed-time story sort of way, seemed lacking and repetitive aside from the catchy and ambient main theme. Other sound effects and voice over are done well, though, and only help to draw you into the world of Lemuria. Unfortunately, the only voice over in the game is the narrator during the brief and sparse cut scenes, and I can’t help but wonder if the main cast had voice overs too, maybe it would help to sell the rhyme scheme a bit more.

Overall, I think Child of Light is an exquisitely beautiful game, that unfortunately just falls a little short of the mark. Frankly, growing up as a kid, I never would have imagined a game could look this good, like an illustrated picture book come to life, ready to explore. It’s a solid and thoroughly fun world to explore too, but it’s a little too eager to please in places, and a little style over substance in others. The entire game being written in rhyme, ultimately, holds it back too and the story, although sweet, could have used more twists and turns. Despite these flaws, I can’t help but wholeheartedly recommend Child of Light. Yes, because it’s a sumptuous, curl-up-in-a-blanket-stormy-night sort of game that can take us back to our youth, but also because I want to see more. More like this from Ubisoft, more like this from other big developers. The games industry is a far more exciting place with the prospect of a company such as Ubisoft making a game like Child of Light. Pick it up, put the kettle on, enjoy.

Comments

Comments