Ether One Review

I’m beginning to think that the prevailing philosophy of videogame genres – the idea that everything can be pigeon-holed into one or two pre-determined classifications by an invisible committee of shadowy Illuminati types – might just be a blessing in heavy disguise. Now, before all you precious indie types jump down my throat, I’m not denying that genre is a restrictive force. Here we have a medium with the greatest potential for storytelling in the history of the human race, and yet we insist on following the same trails, time and time again, with only minor alterations. The first-person shooter. The platformer. The point-and-click adventure. Could we not unleash boundless creativity if we stepped out of these pre-set frameworks? Why does it have to be a first-person shooter? Why not a first-person-walk-about-adventure-where-you-pick-up-ribbons-but-also-solve-puzzles-if-you-really-want-to? Calm down, Microsoft Word, it’s artistic license. Take your wavy red lines elsewhere.

However, the truth is that no matter how often you bang your ‘creative freedom’ drum, we have genre for a reason. Genre offers stability. The moment you step off those well-worn trails, you have carelessly thrown your only map into the wind, and navigating your way towards a satisfying end product is going to be all the more difficult. Some games succeed, some jump-start their own genres as others follow in their wake, some become cult classics, and many of them simply fail. Ether One feels like one of those games: a game that takes just a tiny step out of the bounds of what we construe as typical, quivers uncertainly for a second, and gracefully collapses into a heap. Does that make it bad? Well, I’m not going to bloody well tell you yet, am I?

At any rate, Ether One certainly starts on a very promising footing. You are a ‘Restorer’, a sort of experimental medical patient who can – with a little bit of help from a machine that looks like it deserves its own SCP page – project yourself into the minds of other patients, treating their mental illnesses by traversing the visual manifestation of their psyche. You’ve been roped in by a slightly shady private medical institute that clearly has a great deal of money – very little of which is apparently spent on staff, because you never actually see another living soul working there – to treat the dementia of an elderly British woman by the name of Jean Thornton. The introductory sequence, which sees you descend through the facility, ‘meet’ your supervisor and strap yourself into the aforementioned machine, is fairly effective at establishing the central premise while hinting that there’s far more going on than immediately meets the eye here. “Aha,” I thought, mind swelling with pleasant comparisons to Bioshock and Half-life. “This will be excellent. A well-paced, well-told linear first-person story with the option to dig deeper if I choose. Let’s jack in. Or, you know, whatever you neurologists call it. Punch it. Surf the brain-tubes.”

Even as far as the first proper area of the game, things still look fairly rosy. After being deposited in Jean’s mental landscape – her birthplace, a deserted 1960s seaside town in Cornwall quaint enough to make an Enid Blyton novel look like a gritty crime drama – I was given both a meaningful task and reasonable motivation for doing so: get to the bottom of the mine, destroy the crystal that’s driving this lady mad, and go home for tea. Apart from eliciting a tiny blip on the arbitrariness meter, that seemed like a reasonable course of action, so off I trotted, solving some agreeable Amnesia-esque puzzles along the way. Warning lights on the arbitrariness meter only really began to flash after the final puzzle of the area, in which – bearing in mind that this is every bit as nonsensical as it sounds – placing a book on a desk somehow caused a nearby broken film projector to miraculously reform and open a nearby door. An exciting scripted sequence followed, and at the flick of a switch, I suddenly found myself playing Master Reboot again.

Alright, perhaps that was uncalled for. Ether One isn’t quite as bad as Master Reboot, but they both shoulder more or less the same problem: namely a lack of cohesiveness brought on by attempting to recreate a dream-like state. From here onwards the game dumps you in a series of large open-ended areas to explore, and with the demise of linearity all semblance of coherent storytelling is carelessly bundled up and thrown out of a speeding train. You’re supposed to piece together the plot from the notes you find lying around and the transmissions you receive from your doctor, or at least I assume that’s the intention, but there’s zero guarantee that you’ll encounter them in an order that makes any degree of sense, and there’s no in-game journal to keep track of them in the first place. If you are like me, and have the memory of a sieve that was recently used as a helmet in a Prohibition-Era Mafia shoot-out, this is an absolute nightmare. It’s not like, say, Half-Life or Dark Souls, where you can cheerily blast through the game without paying attention to the back-story and still get a halfway-satisfying ending: if you don’t have an extremely firm grasp on what’s going on, then the surreal sequences and ending will wrench away whatever grip you had on events. It’s frustrating because the game is clearly marvellously written in both the plot and dialogue, and the final twist still managed to hit me like an overloaded semi truck, but it’s so heavily fragmented that it’s practically impossible to make sense of without keeping copious handwritten notes while constantly backtracking. Imagine that you’re reading a best-selling book, but each chapter is in a different language, from the perspective of a different character, and the pages have been scattered across Yorkshire. Also, you’re not allowed to pick up any of the pages. Wait, stop; I have a great idea for a television show.

Each area has two main tasks: find eight ‘memory fragments’ (represented by red ribbons), which will advance the story, and complete several elaborate environment puzzles, which will expand on the story in some significant way. If you’re wondering why the game works like this, the developers essentially claim that it’s so that anybody can experience the story, but I’m not sure that I buy that. The story hardly seems complete if you don’t go out of your way to actually solve the puzzles and get the little expansions that come with them, so it seems to be a toss-up between experiencing a cloudy, insubstantial story or working your fingers down to bloody stumps for a satisfying one, neither of which really sounds that appealing.

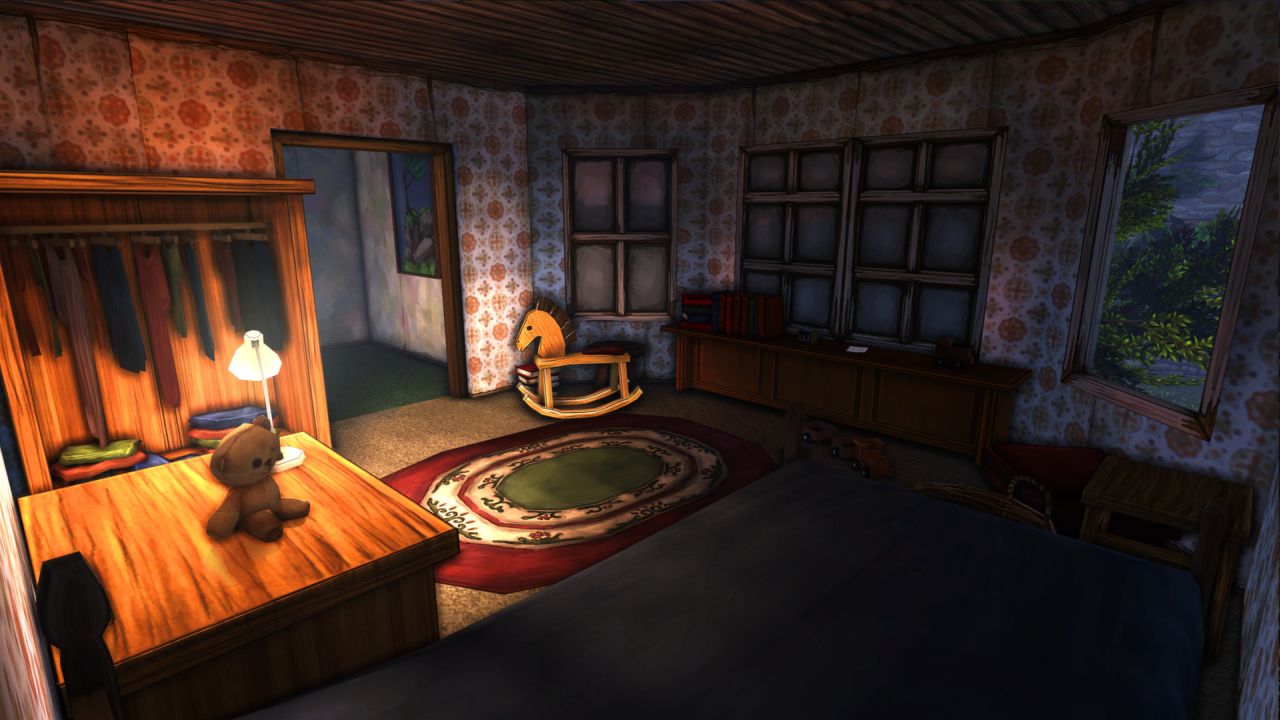

Now, if you fancy yourself as a spotter of unsavoury videogame traits then you’ve probably been jumping up and down for the duration of the last paragraph yelling about scavenger hunts – in your head, I mean, unless the people around you are particularly considerate – but hold your horses, because in Ether One it actually works fairly well. Searching for ribbons gives you an incentive to explore, and the environments are minutely-detailed enough to make it enormously rewarding. Many areas tell a story all on their own, like the holidaymakers’ house full of Morris dancing equipment or the electrical laboratory in the blacksmith’s basement, but even simply going from door to door, sifting through people’s cupboards, reading their notes and pinching their important puzzle items is strangely absorbing. It carries that same illicit thrill of going through people’s private lives, uncovering their secrets, that has always been in the Thief games, but with all the NPCs tactfully removed. Your goal is indeed still ultimately just a scavenger hunt, but it’s really just a structure to keep the exploration from spiraling off into pointlessness, and when the exploration is this good, that’s totally fine.

On the flip-side of the gameplay coin, things get a lot murkier. I mentioned puzzles, and there are indeed puzzles – intricately-connected puzzles of the sort that won’t seem too unfamiliar to a keen point-and-click adventure player – but they share the story’s problem in that they’re almost utterly opaque. I would have thought that having a definite goal would be a start, but Ether One seems content to just dump you in an area and sit back, arms folded, as you fiddle with the scenery. When you don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing, that turns many puzzles into exercises into trying every last interactive action until something happens, and even those with an implicit goal are troubled by the game’s obnoxious refusal to let you retain important information. I know I’m supposed to keep a pen and paper handy for this sort of thing, but I’m not sure why. It just seems like a method of artificially gating the puzzles, especially considering how many times you end up finding written codes for locks in entirely different sections of the game for no better reason than “you had better jot this down or you’re going to get terribly stuck in about an hour”.

The infuriating part is that the puzzles themselves seem to be actively taking refuge in their muddy presentation. Often I would stumble – usually by luck – upon some simple task, like levers that needed to be set according to a diagram, or a piece of environment that just happened to work with the inventory item I had found, only to feel my enthusiasm drain away as I realised that I had once again grabbed onto the middle of the lengthy, tangled thread of logic, and that nothing I had done would have any effect unless I went and triggered a bunch of other arbitrary nonsense. You know what, forget it. I’ll go back to collecting ribbons and reading people’s secret diaries.

It’s a shame because Ether One actually makes some fairly remarkable departures from the usual first-person adventure game format, which are certainly worthy of discussion if not actual praise. Your inventory screen, for instance, is replaced with an abstract little apartment that you can teleport to at any time and dump items into. It’s an interesting way of explaining away the age-old question of how the adventure game protagonist of the hour is able to carry fourteen miscellaneous knick-knacks around without shouldering a backpack that’s roughly the size and weight of a motorcycle, and – mostly due to the near-instantaneousness of the teleport combined with Ether One’s already fairly-leisurely pace – it’s not as unintuitive or flow-breaking as it might sound. Furthermore, in the vein of games like Dreamweb, the items you can pick up and interact with vastly outnumber the items that are actually relevant to the puzzles, invalidating the age-old brute-force solution of looting everything in sight like an extremely ambitious burglar and rubbing every last thing in your inventory on the current obstacle in your path. It encourages you to consider whether the item you’re picking up is going to help with a puzzle at some point in the future or whether you’re just hoarding it because you can. Of course, this is something of a lost cause since there’s no way of knowing what the puzzles will actually be, but that’s no reason not to applaud it, eh?

Ether One feels tangled, deliberately obfuscated, even impenetrable at times. If you have the patience to lay it all out, straight and organised – through a combination of constant backtracking, excessive note-taking and several months of forum-board speculation – then what you will uncover will be intensely satisfying, but is that really a valid excuse? Don’t get me wrong here; I love a game that just puts you in the thick of things and subtly clues you in on what’s going on, but there is a limit to how subtle those clues can be. Nobody likes being bludgeoned repeatedly with cutscene after cutscene (except maybe Metal Gear fans, wahey) but Ether One sits on the far end of the spectrum, and in a game as heavily story-driven as this, that doesn’t seem like a reasonable approach. No such excuse can be pointed at the puzzles, of course, which just combine Master Reboot’s surreal dream-like confusion with the old adventure game problem of steadily refusing to tell you what you’re actually trying to blooming achieve.

Mind you, if I was going to spend several weeks’ worth of gaming time trying to unravel an overly-complex plot and solve a bunch of puzzles that ran on dream-logic, Ether One would be one of the few games that would remain bearable throughout that time. As already mentioned, the atmosphere of Pinwheel, Cornwall, is absolutely superb, delicately balanced between poignancy and being just a little bit sinister. There is indeed something very eerie about walking around a perfectly-preserved village without any people in it, but the snippets of music, sound cues and occasional transmissions from your supervisor make the whole experience a lot less depressingly lonely than it could have been. It’s one of those rare games where the ambience is rich enough to hold my attention all on its own, like lazily strolling down the street in GTA IV and just watching the city buzz, its citizens blissfully unaware of the massacre they’re going to bear witness to once I spot a fast enough car.

I’ve levelled a lot of complaints at Ether One, most of them fairly serious, but it still gets out of here with a slight recommendation on the basis that the positives outweigh the negatives. While the storytelling doesn’t even hold a candle to the likes of The Stanley Parable or Gone Home, the story itself is fairly elegantly written if you can keep a handle on it, and Ether One’s efforts at gameplay clearly outshine both of those overblown walking simulators. I did whine at length about the puzzles – and not without good reason – but if you’re prepared to write down every last detail you come across then they’re generally acceptable, if muddied by their often-nonsensical logic. Even the scavenger hunting, derided though it is, is an effective incentive to turn over every last stone you can see. If you blast through Ether One, doing the bare minimum that’s required to make the story progress and disregarding everything else, then you’ll find a short, confusing Dear Esther clone. If, on the other hand, you take the time to solve the puzzles, reconstruct the story, search every last corner for clues and generally savour the game like a swig of expensive liqueur, then you’ll find an intensely atmospheric story marred by only occasional annoyances. Me? I’m cautiously optimistic about whatever White Paper Games decides to do next. Let’s hope it’s not called ‘Ether Two’, though.