Satellite Reign Review

Of all the trends in game design to emerge on this side of the 1990s, undoubtedly one of the most important ones was the understanding that sometimes players will screw the pooch and there’s nothing you can do about it. No matter how hard you try, some people will put puzzles into unwinnable states, waste all their ammo on an invulnerable boss, get lost on the way down to the shops and accidentally sell all their clothes to the only merchant in the village too spiteful to sell them back at the same price. Some made an honest mistake, some just had an unfortunate misunderstanding, some are just going through their ‘manchild gaming YouTuber’ phase, but the important thing is that you accommodate for them. In most games, this is all about extending a helping hand downwards to those who seek it; an infinite ammo cache in a secluded corner, a means of resetting the room, an escape mechanism for when all else fails. “You messed up, kiddo,” says the game, “but I got your back.” But why should failure be greeted with nothing more than a correctional shove? Some of the greatest games out there are those where stepping into a security camera’s arc is nothing more than an excuse to improvise and manage the forthcoming catastrophe. That’s the kind of game Satellite Reign is: a good game to play well, but a fantastic game to play badly.

Anyway, it’s the generic cyberpunk future once again, in all its rain-slicked, neon-streaked, trench-coat-wearing, pollution-choked, anti-authoritarian glory, and the oppressive power of the week is Dracogenics: a cloning megacorporation with the moral compass of a paparazzi photographer crossed with a Japanese giant hornet. As expected, everybody making more than the average pay-check is corrupt and the government is mysteriously absent, so it’s up to you, your resistance group, and your squad of four cybernetically enhanced agents – the soldier, the support, the hacker and the infiltrator – to take down The Man and make life a little bit less dystopian for everybody else. Yeah, it’s no Snow Crash, but it puts a definite goal in front of you and gets out of the way so that the real storytelling device can step in: dynamic, unscripted, interlocking gameplay systems.

What’s strange about Satellite Reign is that if you took its mechanics, untangled them all from one another and laid them out on a disinfected operating bench, the only thing that would make most of them remarkable at all is the format they’ve been crammed into. It’s a squad-based stealth-action RTS (not entirely unlike Syndicate) in a mostly-seamless open world – alright, sounds good – but stealth is about staying out of line-of-sight while crouching behind chest-high walls, combat is about selecting all your agents and clicking on the thing you want to die, and pretty much every obstacle is bypassed by selecting the right person for the job, clicking on it, and waiting for a progress bar. Off the top of my head, the only really remarkable mechanic is the ability to snatch people off the streets and use their DNA in your cloning vats – yes, really – but in practice that just means scanning randomly-generated passer-bys until you find somebody with a nice enough stat bonus or a large enough willy to justify ripping off their genes.

But that’s okay; looking at mechanics individually is completely the wrong way to look at Satellite Reign, for the same reason you don’t look at Deus Ex in terms of its ghastly gunplay or naff excuse for a hacking minigame. Satellite Reign is a game that throws a lot of toys into an inflatable pool, pushes you in, and lets you make what you will of them. What matters isn’t their individual strengths so much as the way they interact to create an open-ended experience where your approach sends ripples through the world. Like any game with emergent gameplay, it’s a wonderful font of stories, and if I had the avant-garde reputation to get away with it, I’d spend the rest of this review just recounting them in excruciatingly minute detail. Your trail of chaos – and there will most assuredly be a trail of chaos at some point – is made all the more colourful by the fact that you’re controlling four agents completely independently, each with their own impact on events. One could be getting arrested, one could be on the run, one could be sheepishly explaining to a policeman why they’re hacking into an ATM at four in the morning while wearing Shadowrun cosplay, and one could be gunning down people in the streets just for a laugh. If your path through the likes of Deus Ex is like dropping a ball into a pinball machine, watching it ricochet back and forth triggering all kinds of blinking bumpers, then your path through Satellite Reign is like dropping four balls in at once and being momentarily overloaded by the resulting storm of blinking lights and annoying sounds. The potential for complex, constantly-shifting situations is, to be frank, bloody brilliant.

That potential isn’t always fulfilled, though. Satellite Reign peaks when you have to split your squad up and frantically try to coordinate their disparate abilities, but a lot of the time – especially in the first zone, where strongholds might as well roll out the red carpet for you for all the resistance they put up – it’s easier to just get everybody to run around in a group like a gang of impish schoolchildren. The level design is clever enough to provide options that make each of the four classes feel integral – a security terminal for the hacker, an oiled-up ventilation duct for the infiltrator, a structural weakness for the soldier and a book of Chinese proverbs for the support – but unless events conspire to draw your squad apart, or require that they perform multiple actions in tandem, it often makes more sense to stick together and just bypass obstacles with whatever method happens to be most convenient. It certainly doesn’t help that a lone agent in an all-out gunfight stands about as much of a chance as one of those inflatable flailing tube men you see outside car dealerships, so you’re likely to band everybody together just to bump up their survival odds when everything goes pear-shaped.

But like I said, things going pear-shaped is the essence of Satellite Reign. It’s the kind of game where even the most immaculately planned operations invariably degrade into complete chaos, but the odds of getting out alive with opportunistic, desperate tactics are still good enough to make such an outcome satisfying. There are so many ways that things can go pear-shaped, and so many degrees of pear-shaped-ness to achieve, but the spectrum is so long that things can be salvaged long before they degrade into a hopeless gunfight against an army of ticked-off quadrocopters. You can get caught with your weapons out in a shopping plaza and fined a hefty sum – that’s right, private security guards in the dystopian future can actually deal with threats without resorting to concentrated gunfire – but as long as your infiltrator can slip around the back and run somebody through with a katana, you can probably get away in the confusion without even setting off an alarm. This is probably all making the game sound a bit too forgiving, and for the first few hours there’s probably some truth to that, but thankfully things are balanced such that this feels less like a series of safety nets and more like being stuck in a situation that you can never quite get a handle on. And that’s great.

Still, I wish that the tight spots I ended up in didn’t so often feel like somebody else’s fault entirely. Agents feel sluggish and slow to respond to your inputs, as if their cybernetic brains are receiving commands via the NBN, which is a bit of a problem when security consists of more than one rusting cyborg and his overly-aggressive Roomba. The game shows you what positions everybody will take up if you click ‘move’ on a given location, but actually getting them to take up the positions you specifically want – that is, ones where your pillock of a fourth agent isn’t left standing around with his head poking out – is an unreliable and fiddly process suitable only for watchmakers and people who milk spiders for a living. And what about interactive elements? Whether it’s a terminal, a hardware panel or the back of an unsuspecting guard’s cranium, if your agent isn’t precisely positioned correctly for the action then they’ll just stand around sucking their cybernetic thumb until they decide to reorient themselves. Maybe it seems odd to nitpick over such tiny control quirks in what is functionally an RTS, but it’s a matter of focus: a moment of hesitation that might’ve otherwise made a few zerglings late to the space marine buffet could instead mean overtime at the cloning vats (or worse, a trip to the quickload screen) .

But let’s talk about upgrades. The story, for lack of a better word, is essentially about building up your four agents until they’re strong enough to kick down Dracogenics’ front door and clean the place out like it ain’t no thing, and the game’s upgrade cycle neatly reflects this: you break into compounds, steal their prototype technology – that is to say, you conduct tactical espionage operations, mm hmm – research how to replicate it and then use it to help break into the tougher compounds just down the road. It’s a fine way of organically gating progress, and like just about everything else in the game, you have plenty of freedom to equip your squad as you see fit. Of course, that doesn’t always mean deciding how to build them is a brain-buster or anything; grenades can wipe a small army off the map, medical wands can instantly heal an agent from halfway across the screen, and if you’re like me – terrible at any strategy game where you can’t stop for a cup of tea between each move – then the future-steroids that put everything into slow-motion are an absolute godsend. Compare that to a new gun that does slightly more damage to armoured enemies, or a head augmentation that gives you a meager health bonus, and it’s just not the same kind of utility.

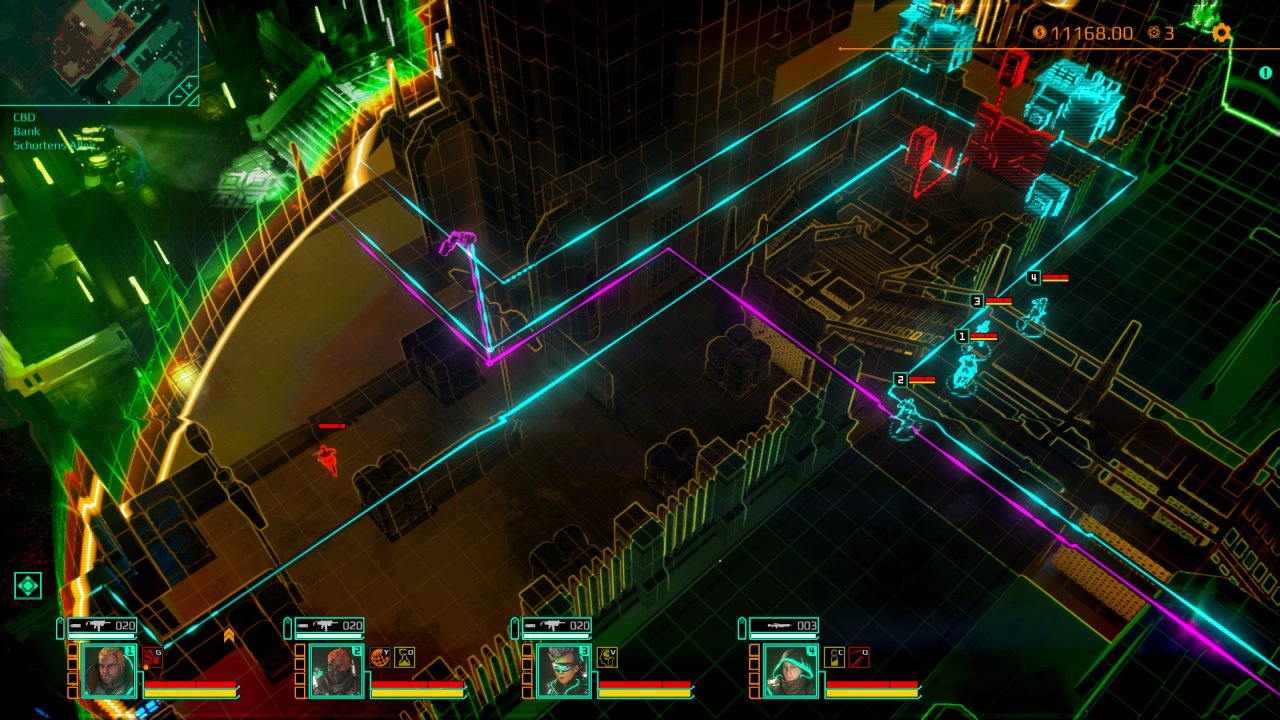

On the other hand you have the scanner, which is really just too useful. At the push of a button, without any energy drain or penalty, your support will scan his or her surroundings, allowing you to identify people of interest, see the city’s cabling underfoot, and pick out interactive elements from the fluorescent multicoloured jumble of the city streets. While this is undoubtedly useful, and looks cool to boot – overlaying wireframes onto everything like your agents just cut a hole in the space-time continuum and stepped into the level editor – it has the same problem as Batman’s detective-vision and Garrett’s edgy-goth-lord-vision in the sense that there’s no practical reason not to just wander around with it on all the time. Maybe it’s unfair to pick on Satellite Reign out of all the games that do this, but really, why? Hiding information away like this until I press a button isn’t engaging or challenging; it’s just an extra step that lets you get away with less readable visual design. The only interesting feature at work is when what you can see is limited by the scanner’s radius, forcing you to get creative in order to work out where a gas main leads or where the control panel for a camera is hiding, but it hardly comes up often enough to justify building a whole system around it.

Then there’s the whole business of the game being technically a sandbox. Unsurprisingly, it comes with the sandbox requisite avalanche of doodads to hunt down in between expeditions into enemy strongholds – ATMs to hack, revive beacons to set up, lore snippets to download, researchers to coerce – but they’re all valuable enough to make finding them feel like a worthwhile task rather than a meaningless Ubisoft collect-a-thon. What’s more interesting is how the continuous open world – well, almost continuous; it’s divided into four zones for pacing reasons – adds so much to the process of getting into somebody’s complex and stealing their secret tech. Now that literally everybody else on the planet has logged forty-something hours into The Phantom Pain I’m sure this seems like a moot point, but being able to work around the boundaries of hostile areas, locate hidden entrances, soften up points of entry and vanish into the market across the street all feel like wholly unique experiences that recognize the unsung joys of infiltration in an environment that doesn’t just stop at the boundary wall. Getting one character to blast open the service entrance and flee while the rest of your squad lean against the wall and whistle nonchalantly is a hilariously effective tactic, and the Hitman-esque relationship between restricted and neutral areas – wherein guards will escort agents outside as long as they’re not doing anything too suspicious – leaves room open for all kinds of shenanigans that just wouldn’t be there if you were simply dropping in from an overworld map. And once again, unexpected interactions between the game’s systems make it feel so alive: I’ve seen compound guards getting into fights with street cops over an errant droid, civilians getting perforated by minigun fire for stumbling through the wrong door at a security checkpoint, even pursuers being thwarted by spontaneous traffic jams.

Satellite Reign is the kind of game I want to see more of. It’s open-ended, deep in strange places, remarkably atmospheric, and considering that the last game to resemble it came out in 1996, as close to unique as it’s going to get. It’s not an especially stellar RTS, nor is its stealth much to write home about, but it redeems itself as a creator of moments: stories of last-stand shootouts, operations going thoroughly awry, AI quirks and disorganized escapes. Moments that happen because of how you approach your tasks and the degree to which you thoroughly botch them, not because somebody wrote a thing dictating how they were going to play out. So give it a shot, why don’t you, before all those moments are lost… like tears in the rain.