DreadOut – Act 1 Review

I think it’s safe to say I’m officially sick of zombies. They’ve been a stock enemy in games since the days of the punch-card, ubiquitous and as universally acknowledged as dust on the mantelpiece, but in recent times, largely due to the success of that ‘act like a complete tosser to your fellow man’ simulator DayZ and the outbreak – if you’ll excuse the term – of open-world zombie games, they’ve enjoyed something of a resurgence. It’s a disappointing state of affairs, frankly, because zombies are never really going to be fresh again. Once you’ve done slow shambling zombies, fast marathon-running zombies and zombies with improbable projectile attacks, what else is left? Zombies don’t have complex motivations or strategies; the only time they ever do anything remarkable is the split second between being hit by a grenade and lying around on the ground in a hundred fleshy pieces. You can buff those gibs with your shiny new graphics engine until the player can smell the rotting meat, but it won’t make zombies a remarkable enemy type ever again.

Strangely enough, the genre that seems to be bucking this trend right now is, of all things, survival horror. Outlast? Mutilated patients, great stuff. A Machine for Pigs? Full of pigs, love ’em. Daylight? Alright, that was a congealed pile of soggy tissue paper and sadness, but did you read about anybody complaining that there were too many zombies? Didn’t think so. And now there’s the first act of DreadOut, an indie survival horror game carrying the intriguing promise of having enemies based on creatures from Indonesian myths and folklore. If that doesn’t sound like a breath of fresh air, I don’t know what does. Especially the title. Seriously though, you can’t treat capital letters like that; they’ve served us well for far too long to be roundly abused.

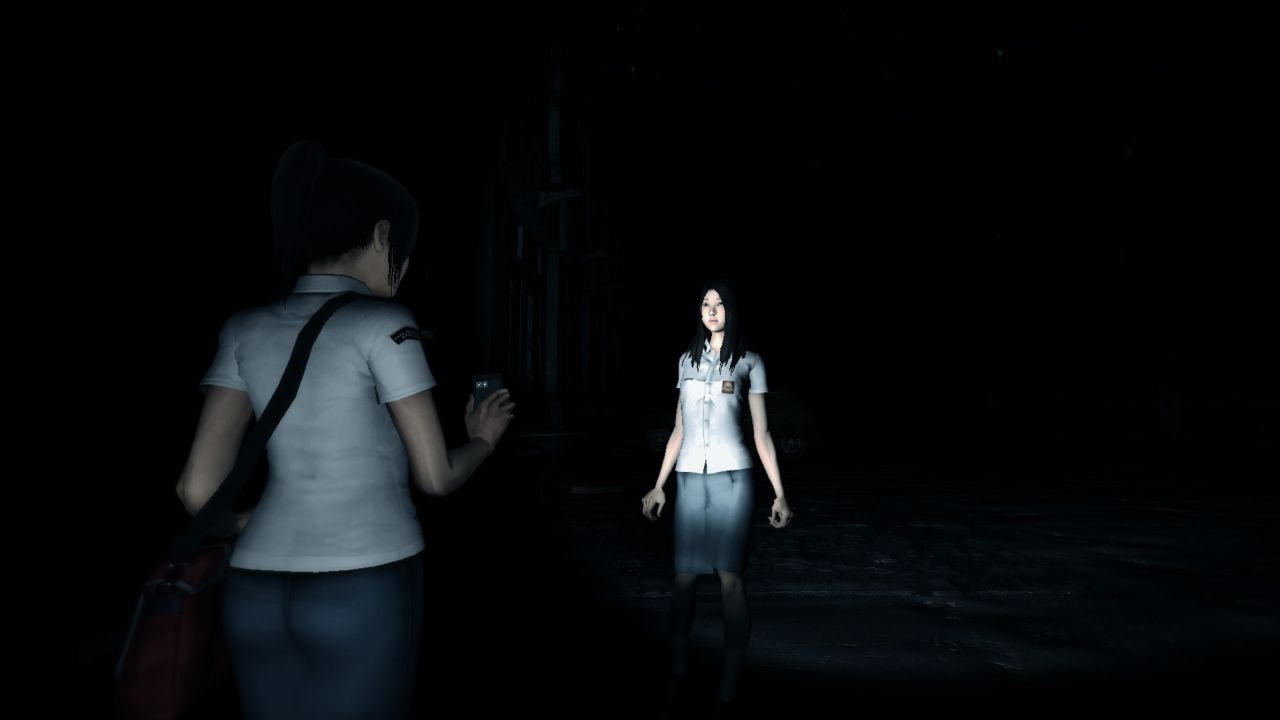

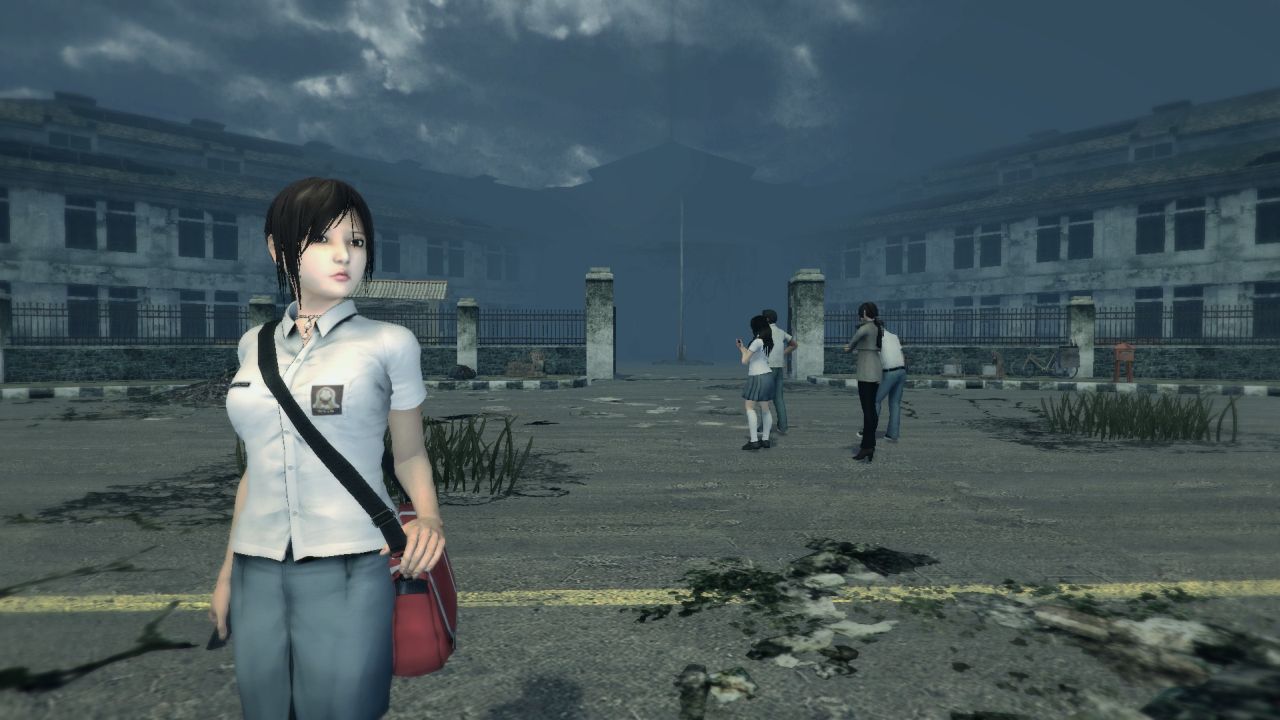

Of course, one has to always be wary that what appears to be a breath of fresh air isn’t just the spittle-flecked yawn of somebody experiencing some cliché horror game exposition. You play as Linda Meilinda, one of several high school students on a holiday trip that goes wrong when the group takes a wrong turn and ends up wandering into a deserted town. The whole place has clearly been vacated in a hurry and there might as well be a big tatty banner in the town square that reads “Congratulations from the Silent Hill Committee on your recent Town With A Troubled Past award”, but they nevertheless decide to explore. A combination of coincidences and supernatural happenings separates the various group members, leaving Linda alone in an abandoned school to save both herself and her friends from whatever it is that’s out to make their lives hell. It’s hardly original, but it gets presented in a light that’s just new and interesting enough to let it slip comfortably out of the way, leaving the game to knuckle down and get a nice tight grip on the bits of your brain associated with soiling one’s pants. There’s actually a fair bit of ambiguity as to what exactly happens to the group that fragments it and leaves Linda all alone, and although it leaves a lot of questions unanswered I actually kind of like it. You could say it affords the story an extra air of mystery, even if the mystery in question is “what on earth were you doing while all this was happening, you pillock?”

Since we’re making such a big deal of the enemies, close examination should probably be afforded to them. Maybe I’m just too culturally ignorant to appreciate the subtleties of DreadOut’s monsters, but I’m afraid I’m a tad underwhelmed. The very first enemy you meet in the game – and I’m not making this up, seriously – is a giant pig. Not an Amnesia-esque pig-man-monster, just a pig. Alright, maybe it has a humanoid face, but it’s still a pig, and it’s hard to feel threatened by a supernatural monstrosity that goes “oink”, has a hairy bottom, is incapable of climbing stairs and cannot outrun a teenage girl. Next up is an actually fairly spooky invisible woman, who fares a bit better right up until you encounter her method of attack: a full-on obnoxious first-person jump-scare. Oh yes, and if you don’t kill her by attacking her weak-point, she’ll just respawn a few feet away and do it again. And again. And again. I’m not saying you can’t startle the player occasionally, Digital Happiness – and incidentally, that’s a pretty upbeat name for the developers of a game like this – but after the fifth time I was a bit too busy engaging in a long, luxurious yawn to really feel the full effect of it, you know?

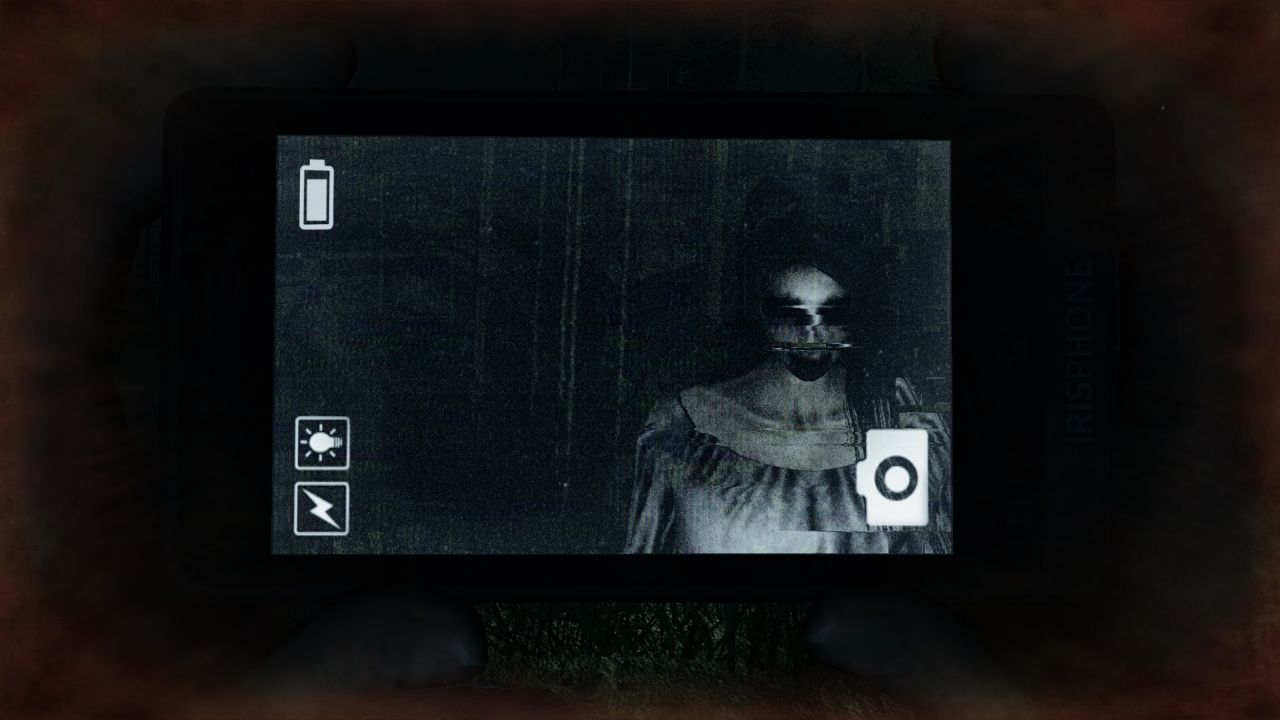

Speaking of attacking weak points, if you’re the sort of person who has grown accustomed to the first level of every game being a tutorial in a big baggy overcoat then you are in for a nasty shock. Everything you need to know about the gameplay is written in a handful of ‘How To Play’ screens that can only be accessed from the main menu, and while I’m not complaining about getting a break from the overbearing hand-holding tours, it does seem like a crude solution when the gameplay is so achingly far from self-explanatory. To put this into context, the main character’s primary means of defence is a camera phone, which will – under the correct circumstances, at the right distance and with enough cooperation from its target – destroy ghosts. It’s actually a pretty cool idea that adds some interesting points of depth to gameplay – I like, for instance, how you don’t start off with a map, and have to instead have to take a picture of one somewhere – but unless you played Fatal Frame – which was apparently a PS2 survival horror game with a similar mechanic – that sounds like the most counter-intuitive combat strategy known to humanity. Oh no, there’s an unspeakable monstrosity chasing you! What should you do? Run away? Hit it? Throw rocks? Engineer an elaborate trap? Nope, you should take a picture of its big ugly mug seconds before it gores you. Little notes like ‘some puzzles involve taking pictures of very specific things from very particular vantage points’ also wouldn’t go amiss.

What really gets me is that the game never justifies why any of these mechanics make sense. Sure, the inexplicable can do wonders for atmosphere, but that only goes so far before the only explanation left is ‘we wanted to be Fatal Frame’. What is it about your phone’s camera that makes it the perfect means of supernatural defence? Did Linda buy it from a sketchy electronics stall that mysteriously vanished when she went back to look for it later, or are the ghosts so self-conscious that the mere sound of a camera shutter is enough to drive them away? And what about being able to just inherently sense nearby ghosts? I’m grateful for the feature, believe me – especially when the invisible whimpering jump-scare lady is on the prowl – but why exactly Linda is sensitive to the machinations of the non-living, anyway? At least the Silent Hill games would contrive a way to drop a broken radio into the protagonist’s lap.

Having said that, if you’re going to contrive a game mechanic built around slowly assembling the world’s most disquieting album of holiday snaps, you might as well do it the way DreadOut does it. You spend most of your time walking around in a third-person mode, navigating the area and searching for puzzle items, but for combat you have to bring your phone up to your face and deal with the supernatural nasties in first-person, staring them right down before you start clicking away. It doesn’t sound like much, but the way it gets presented does wonders for the game’s sense of horror. With the phone so close to your face and its effective field of view so small, looking through it feels terribly claustrophobic, like peering through a sniper scope without the comforting weight of a high-powered rifle in your arms. However, some ghosts – like our old friend, five-jump-scares-in-ten-seconds – are completely invisible unless you look at them through the camera viewfinder, so you’re in a constant uneasy state of flipping back and forth between third- and first-person, trying to maximise what you can see in order to make sure you’re not about to get jumped by something with a face like a basket of rotting fruit. It’s a clever way of making you feel blind and vulnerable without surrounding you with impenetrable pea-soup fog, or submerging you in pitch darkness that would make the Tomb of the Giants feel like a showroom by comparison.

Nevertheless, I felt that the whole effect was somewhat diminished, knowing that my only real concern was the possibility of something startling happening to me, the player, while in first-person mode, and not what actually happened to Linda. The essence of a third-person horror game is that we sympathise with the character on-screen enough to care about what happens to them, and DreadOut just sort of absent-mindedly leaves that by the wayside. There is precisely one character in the entire game with a distinct personality more engaging than a piece of soggy cardboard, and not only is it not Linda, but it is the person who goes missing about fifteen minutes in and never gets seen again. I know games have had a funny obsession with mute protagonists over the years, but Linda’s apparent complete lack of a voice really limits the amount of expression available to her. Actually, you know what? I don’t think she’s mute at all. I think she just doesn’t speak because she knows she’ll be bestowed with the same voice acting capability as the rest of the group (i.e. that of an infomercial presenter cold-reading lines ripped straight from the first draft) .

And it has to be said that after a while I really was hanging a big mental question-mark over the whole ‘survival horror’ thing. There really doesn’t seem to be a lot of survival going on here. Your camera has an infinite battery life and can store an infinite number of pictures, so there’s no sense of needing to choose your shots carefully, and while you can be damaged – your health being represented by a monochrome screen overlay – death doesn’t seem to hold any penalty besides setting you back to the last checkpoint, which usually was only a few minutes ago at the absolute most. If it wasn’t for the presence of puzzle items and occasional titbits of back-story there really wouldn’t be any reason to scavenge whatsoever.

Actually, death does have a penalty, and it’s a real head-scratcher. When you die, you are transported to the inky black void of The Abyss (two Dark Souls references in one review, woohoo) and are tasked with walking forwards until you reach a glowing angel-like figure, at which point you are returned to the last checkpoint. The first time you die you’ll find yourself practically deposited in front of the angel, but with each subsequent death you’ll find yourself further and further away, as if your grip on life is getting weaker every time. Great, but the kicker is that you have to run the ever-increasing distance every time you die, making DreadOut one of the few games I have witnessed actively using boredom to punish the player. I’m not saying that it isn’t effective, but I’m not sure it’s the right way to go about doing things.

Of all the games to leave obvious bugs in, though, why a horror game? No, seriously. Do you know what happens when I encounter a bugged enemy in an action game? I laugh (or grumble) and move on. Do you know what happens when I encounter a bugged enemy in a horror game? Two hours of immersion, atmosphere and effective tension go down the drain, leaving me trying to goad the game back into its normal modus operandi – which is to say, making me lean as far away from the monitor as is physically possible – via any means necessary. You just can’t get away with it as easily. There’s one particular sequence that involves running from a giant crawling indescribable thing down an infinite corridor, and while it was certainly intense the first time, subsequent attempts reversed the situation, with me trying to chase it down and trigger whatever subroutine had failed to tell it to start attacking. Any horror game where you end up trying to actively bait supernatural monstrosities into biting your head off and doing unspeakable things to the neck stump is either an ingenious psychological masterpiece or a product in dire need of more QA testing.

I have to admit, though, I’m intrigued to hear that this is only the first act of DreadOut. By the end of the game so far – which is, incidentally, about two to three hours long – you have escaped a building. That’s it. It’s not even as if it’s a big building. Nothing else has been achieved, the plot has not been progressed, there have been no revelations or signs of the school group; the entire act is dedicated to getting through a single door. It makes me wonder how many acts DreadOut is going to have, or alternatively, how much more quickly Act 2 is going to resolve things. Better step on it, chaps, because I’d really like to see the story’s ending before entropy consumes the Milky Way.

The uncomfortable thing about DreadOut – to bring this rambling set of disconnected points to a conclusion – is that I enjoyed it most when absolutely nothing was actually happening. The atmosphere is actually really solid, partially due to the aforementioned camera mechanic but also thanks to some truly excellent sound design; discordant snatches of music and distant ambient sounds that had every cell in my brain internally screaming at me even while I inched closer to a blood-stained cupboard door. Unfortunately, just about everything else the game does only serves to muddy that, and much as I’d like to believe otherwise, you can’t carry a game on pacing and atmosphere alone. Plenty of good games will just do one thing really well, and DreadOut has that, but it just doesn’t redeem all the buggy, awkward, unintuitive nonsense you have to go through to experience it.