Pathologic Classic HD Review

It’s strange to think of a game in terms of being hard to get into nowadays. We’ve long since passed the point where tussling with an abominable interface is just considered part of the experience – the exception being Dwarf Fortress, of course – and game design has evolved to the point where even the most notorious, unwelcoming games have tutorials and controls that are instantly intuitive to anybody who has touched a controller in the last ten years. Even Counter-Strike, a game that eats the ill-prepared whole and spits out their bones, has a tutorial now: it’s called “dust2 24/7 [no snipers]”. And yet Pathologic, despite the number of gushing articles about it in the press, has always stood out as one of those cult classics that’s a cult classic for a reason: it’s bloody impenetrable. Poorly translated, breathtakingly ugly, and like a lot of important mid-2000s PC games, sold nowhere outside the realm of Ebay; it’s the kind of game where the entry barriers are, for many, just too high to bother overcoming. It deserves a remake, if only to tackle the problem of accessibility, and as it happens, it’s getting one. Stranger still, it’s getting two: the full-on, bells-and-whistles, recreated-from-the-ground-up remake, which is still in the works, and the Classic HD one we’re looking at today, which is basically the same game with a fresh coat of paint and some fixes. Still, if that’s all it needs to be playable then no worries, right?

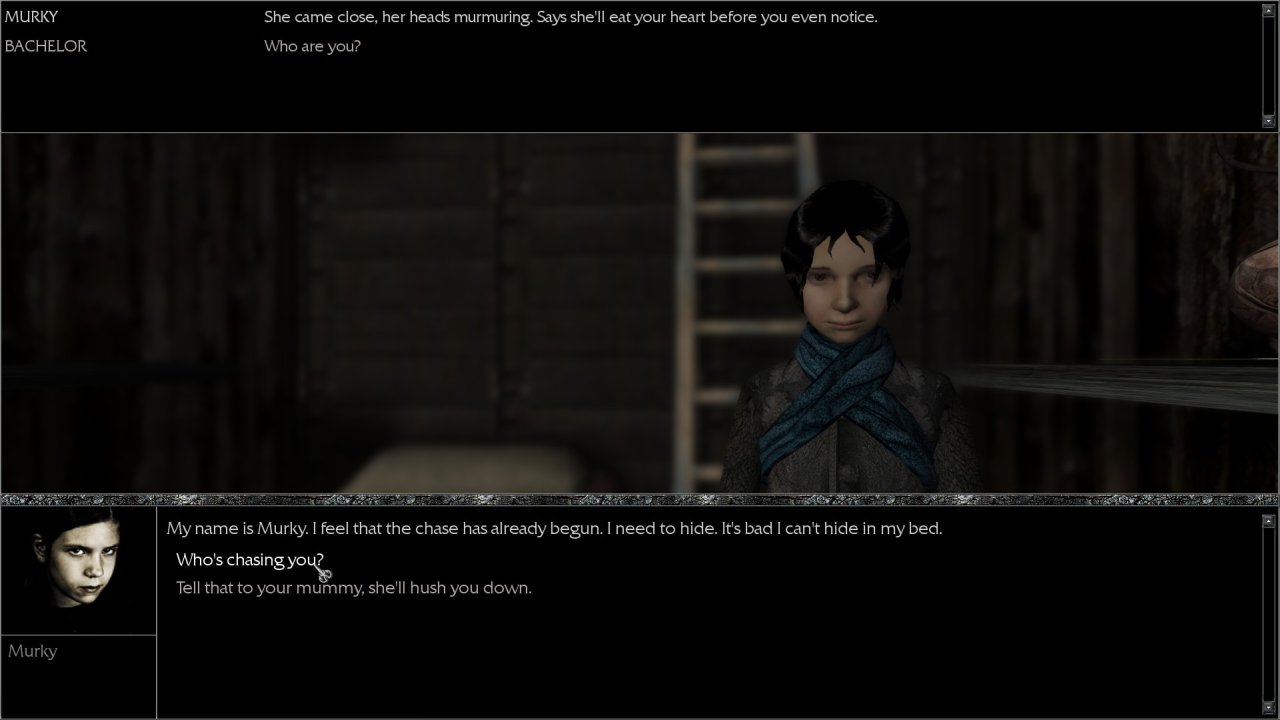

Pathologic is about… well, I’m not sure I can do it justice in a single sentence. It begins on a stage; simultaneously a tangible place in the game, a platform for everything fourth-wall, and a metaphor for the nature of the story you’re about to enter. Three people are talking on the stage, like actors before the play, slipping in and out of character: the Bachelor, a famous, keen-minded doctor looking to prove an outlandish theory, the Haruspex, a messier kind of doctor accused of a crime he didn’t commit, and the Changeling, who I know next to nothing about because she only unlocks after finishing the other two campaigns and this game takes an eternity to finish. These are the playable characters, and by choosing one, you don’t turn them into the protagonist so much as you take on their role. From that point onward, none of you will ever acknowledge that this meeting transpired. Soon, all three characters will separately arrive at a remote steppe town, each for their own reasons, and will become embroiled in a grim, surreal struggle for survival as a strange, lethal disease strikes down the population. Technically speaking, all three characters experience the same general events, but only in the sense that anything that happens to the town happens to them. For all intents and purposes you’re getting three distinct stories, crisscrossing and overlapping with one another in ways that sometimes aren’t even apparent until you’ve experienced them all.

And let’s make one thing clear here: this isn’t ‘survival’ in the usual video game survival sense. Yes, yes, there are a host of bars you need to keep in shape – hunger, exhaustion, immunity, health, that sort of thing – but you’re in a village, surrounded by brickwork and metal and people growing more panicky by the hour. You aren’t going to craft a medkit out of some rags and a bottle of whiskey, nor are you going to find perfectly good food just lying around in a roadside trash-can; everything is limited, everything has a price on it, and if you want to make it out alive, it’s going to be through a combination of spending, bartering, and dirty work. The dreadful algebra of necessity – so-named in the Discworld novel Snuff, which is about as tonally far away from Pathologic as it is possible to be – means that sometimes making it to the next day is a case of deciding what people you’re willing to let be struck by tragedy for the greater good. You can do terrible things to the townsfolk – break into their houses, steal what little scraps they have, stab them in the street and turn out their pockets, offer to run errands and then spend their money on yourself – which would, in any other game, probably earn you a little frowny face on your report card and a trip to Principal Bad Ending’s office. Pathologic does no such thing because it understands the concept of desperation; it understands that you’re doing these things because you truly believe they’re the best course of action, not because you’d already finished the game twice and thought it’d be fun to just murder everybody for your third playthrough or something.

There’s a reputation meter, sure, and it’ll dictate whether or not NPCs in the street decide to try to give you a good thumping, but it’s more of a resource to manage, on-par with health and hunger, than a measurement of whether you’ve been naughty or nice. The closest the game ever gets to judging you is an immersion-breaking on-screen printout at the dawn of each day telling you how many people have died, fallen to infection, and disappeared. It’s chillingly impersonal, making no effort to humanize the people you have failed, or frame the numbers as some meaningful comment on your behaviour: it’s a series of statistics, nothing more. Simple, but breathtakingly effective.

Sorry, sorry. You probably just came here to read about the HD remake bits, didn’t you? I can’t help it, there’s just something so misguided about trying to touch up a game as inherently ugly as Pathologic. Not the intentional ugliness of the factories and the houses and the great hulking Termitary; those, at least, are rightfully built to impose and alienate. Everything is just so unnaturally regular: copy-pasted buildings plonked down like models, streets running perfectly straight for miles, fog that doesn’t so much ‘choke’ as it does ‘conveniently obscure the far clipping plane’. You can polish the textures and models all you like – not that they did all that much; the NPCs are still terrifying wooden mannequins animated by pneumatics – but the town still feels like something that uncoiled from the mind of a level designer who had no choice but to use the clone-stamp tool. No, outside of basic conveniences like in-game widescreen – the FMVs are still in muddy 4:3, presumably because re-rendering them was too much of a hassle – the graphical touch-ups are barely worth mentioning. Far more momentous is the addition of the new English translation and voice-acting, both of which are… well, tolerable. The inherent strangeness of the townsfolk makes the new translation somewhat difficult to judge. Are these people’s lines supposed to be awkwardly-worded and dense as granite slabs? They are, after all, eccentric and isolated and probably on the brink of a fever. Whatever. It’s readable, and from what I gather, that’s a step up all on its own.

So that’s one of Pathologic’s more egregious obstacles out of the way, which is more than welcome when it’s already tough as an old leather boxing glove. Not Dark-Souls-tough or I-Wanna-Be-The-Boshy-tough, where challenges are set up like so many brick walls to repeatedly assault with the stronger bits of your skull; Pathologic is the kind of game to tie you down and methodically lay the bricks on your chest one by one, until the crushing weight becomes too much to bear. Right from the starting gun, you need to look after your own basic survival needs in a town that has never heard of pizza delivery – easier said than done when the air is about as breathable as a bedsheet soaked in gasoline – and with each passing day, things spiral further and further out of hand. Disease strikes, prices skyrocket, districts are sealed off, people begin to panic, thugs jump you in broad daylight, and there’s never an easy way out of any of it. It gives Pathologic a wonderful sense of suffocating hopelessness that’s impossible to find anywhere else; a sense of “maybe you should just turn off the game before things get any worse. You can’t possibly believe you have a chance at success. How long since you last played Deus Ex, anyway? Surely it’s time for another run.”

It’s rare to find a game so unrelentingly hostile, not just in the challenges it presents to you but in its apparent unwillingness to be played at all. There are a lot of bits of Pathologic that go against conventional ‘good’ design, and for the most part I respect them for breaking the rules in bold and interesting ways, but some bits are just a royal pain in the backside for no logical reason. The in-game timer doesn’t run down while you’re in a conversation with anybody remotely significant, which turns out to be a much larger boon than expected when everybody – with the possible exception of the gutter snipes – speaks with the kind of needless verbosity that would make Hideo Kojima put his hands up and go “alright, let’s cut this back a little bit”. You have a journal of sorts that’ll keep track of mission progress, but critical details – likely mentioned in passing by a character after an ideological text dump so thick you have to chew it before you swallow – are often conveniently left out, so even the tasks that are supposed to be simple can leave you trudging around in the rain for hours wondering where the blazes to go next. For the most part I was a good boy who didn’t save-scum – let’s face it: if you aren’t willing to let your mistakes weigh you down more and more with every passing day, you’re kind of missing the whole experience – but I draw the line at losing half the day because there’s no “sorry, could you repeat the actual important bits of your laughably overwritten speech?” dialogue option.

Basic mechanics are explained precisely once, well before you actually have a chance to interact with any of them, and the tooltips on medication are so cryptic that in most cases I just drunk them before bed and hoped for the best, which fortunately tends to work much better than it does in real life. You can barter with NPCs in the streets, which can be extremely rewarding if you happen across the right person at the right time, but understanding how the system actually works is an exercise in (sometimes very costly) trial-and-error. Every moment not spent fighting the disease or clinging desperately to mortality tends to be locked up in managing the convoluted power struggle between the influential figures of the town – all six million of the backstabbing tossers – and yet the game never thinks to provide any kind of reference when a minor character you haven’t seen in three days suddenly gets namedropped like they’re the talk of the town. It’s infuriatingly hard to follow, and even harder to act on.

Now look, that happens to a lot of video game narratives – probably more often than you think – and most of the time it honestly doesn’t matter. Even if you don’t quite understand your motivations, chances are you know what to do and can happily go through the motions until your predicament is rectified. Even in the cases of the most ludicrously overwritten RPGs, it usually turns out that nine out of the ten church tomes they bury you under are so much fluff and character development, padding out the space between “go here, kill this, take that”. Pathologic is different; it’s intoxicatingly rich, like eating Vegemite by the spoonful. There are so many major characters – the Bound, they call them – and everything that comes out of their mouths is valuable. Allegiances and rivalries cover the town like an invisible web, dictated by ideology and circumstance, and as the tension mounts, that delicate web begins to morph. A single line of dialogue can grant so much insight into the town, its history, superstitions, ruling parties, current events and conventions, and it’s terrifying to think that you could simply throw that kind of insight into the winds with a single errant keypress, never to return. I want to know what’s going on. That alone is the kind of praise I have to take out of a glass case and dust off before presenting to a game, and it bothers me to no end that I can’t keep up because it has to be experienced through the medium of awkwardly-worded overly-verbose dialogue trees. You’d think a game this slow could at least throw in a codex or a conversation log or something.

No, I’m sorry: ‘slow’ doesn’t even begin to describe it. Blatant timesink JRPGs are ‘slow’. Ultra-realistic military simulators are ‘slow’. Pathologic is slow on a level that defies belief. It is the shallow, shuddering, drawn-out gasp of a patient on a filthy operating table as the first incision is made. It is a ball of fish hooks being dragged through an overflowing cesspit. You’ll walk and talk and walk again, maybe for hours, just for a chance at a sliver of progress, a single line of plot, and it’s made all the more painful knowing that your time as a character is so precious. The days go by in not-quite-real-time – an hour doesn’t last an hour, but it sure does last long enough for the bell tower chimes to catch you off-guard – so even when the pacing is at its absolute most glacial, every moment is filled with the kind of rising panic you can normally only get by leaving a programming assignment until the last minute and realizing you have no idea what the specification talking about.

The hours that seem to drag on forever will be gone long before you’ve cleared up the day’s shopping list, and it soon becomes apparent that however much time Pathologic grants you, it really isn’t enough. Plenty of games have gotten cheap thrills out of nodding at the clock and telling you that doom is coming for teatime, but it’s usually in place as little more than an incentive to stop dawdling. Pathologic makes it clear, in unspoken words large enough to swallow the town, that there is simply not enough time. You can’t finish every quest, you can’t track down every loose end, and you can’t save everybody. Even the strange, distorted, arrhythmic beat that permeates the interior ambient soundtrack brings to mind a grandfather clock at the end of a very long corridor, quietly counting out all the opportunities you missed. Every mundane task is charged with paralyzing fear, and all you can really hope for is that you’re ready when the plot decides to advance.

That’s what makes the town so fascinating to me, in spite of being about as lively and detailed as a concrete holding cell: it’s impersonal. It’s not there for you, the player; things just happen. There’s a very real sense that the story could happily replace you with an NPC, and indeed, in the case of the two potential player characters you don’t pick, that’s exactly what happens. You are a zookeeper clinging to the back of a hayfever-struck rhinoceros, able to stay atop events and perhaps nudge them in a favourable direction, but by no means able to take control. The plague strikes on the [REDACTED] day because that’s just when the plague strikes. Why should it wait on you? Because you’re the player? Don’t be silly. You’re just another actor.

I still don’t know quite how to receive Pathologic. It’s something of a critical darling, if I can somehow spin that phrase in a non-negative way; a game that’s a lot easier to appreciate in terms of the ideas that went into it than in terms of the actual end experience. It’s all very well going on about all the ingenious things it does to invoke desperation in a strange, constantly-changing town full of complex feuds that stretch back for generations, but the moment we take our heads out of the clouds and dip back into more practical territory, it all falls apart. It’s as if the game had a head full of systemic ambitions, but the only one that really got off the ground was the town’s economy, while the rest simply collapsed into piles of barely-functional mechanics. Every shining beacon of design is balanced by its own slapdash implementation. Burglary, for instance, would be thrilling if you had a functional stealth system and appropriate level design and complex enemy AI, but Pathologic doesn’t have any of those, so instead you lockpick a door, get teleported into a generic house interior that bears little to no resemblance to the outside of the building, walk around openly while a bunch of copy-pasted NPCs make weak attempts at looking distressed, then open up a chest of drawers and stab anybody who chooses that moment to try and jump you. The game is full of moments like this, where the inherent crudeness of its construction all-but soils its elegant concepts, and whether or not you can deal with that depends on how willing you are to focus on what it’s trying to be, rather than what’s actually there. Because what’s actually there, if I’m honest, is a lot of walking from house to house, a lot of dialogue, and a lot of managing resource bars. It’s the ideal versus the reality, and unless you’re ready to meet it halfway, the reality always wins.

No, even if you don’t meet Pathologic halfway, it’s more than that. We like to think we cover a fair spectrum of games here, all the way from the money-burning blockbusters to the cutesy indie curiosities, but the truth is that even that spectrum – the spectrum of games you can sell to people as things they can play – isn’t so wide in the larger scheme of things. I can hop onto itch.io and download a dozen games with no end goal, no mechanics, no promise beyond the ability to momentarily serve up a unique experience. You’re in an interesting place, doing an interesting thing, and sure, it might get old after ten minutes, but what matters is how it makes you feel in those ten minutes. Pathologic feels a little like those games at times, where all the sloppy mechanics are really just obligatory video-game-y niceties that make the experience – the experience of being trapped here, in this surreal town that makes no sense, trying to come to some satisfactory solution – presentable to the public.

Maybe it doesn’t matter if Pathologic is about as much fun as a session of rebar acupuncture. Maybe what matters is the moment when it forever imprints the yawning mouth of the Abattoir on the insides of your eyelids. Maybe it doesn’t matter if the story is impossible to follow, so long as you experience its loquacious dialogues first-hand. Maybe what matters is just being immersed in the atmosphere; not the thick, crushing, depressing atmosphere of Silent Hill, or the grim, gothic, ancient atmosphere of Dark Souls, but the kind of sickening, toxic, stale atmosphere where everybody’s slowly dying and nobody knows what to do about it. Not death as we usually know it in video games, a binary change of state inseparable from the world of muzzle flashes and sharp utensils, but death as a yawning abyss into which every single person in the town, yourself included, is slowly being tipped into.

Ultimately, though, when the pretension wells have run dry, my job here is to give consumer advice, and my opinion of Pathologic is simple: I hate it. I hate its tedium, its clunkiness, its lousy presentation, its stubborn opacity, and its completely barefaced disdain for me as a player. It’s so needlessly prickly on so many levels, caring naught if I’m entertained or satisfied, and my fascination with the story just can’t overcome my distaste for the endless tedious, frustrating errands I have to carry out just to advance it.

But even if Pathologic doesn’t love me, and I don’t love it in return, I still respect it. Everything from the setting to the atmosphere to the story is so singularly unique, and the question of where it’s all going has haunted me for almost a solid fortnight. So much of the inherent awkwardness of video game storytelling stems from the drive to still be entertaining; to tell the player that they’re up against overwhelming odds while still providing a fair challenge, or to tell the player that they’re scared and alone while still having fun combat. Unintentionally or not, Pathologic frees itself from that drive, and in doing so it lives up to the agonizing, tedious, nerve-wracking experience it claims to be.