Ori and the Blind Forest Review

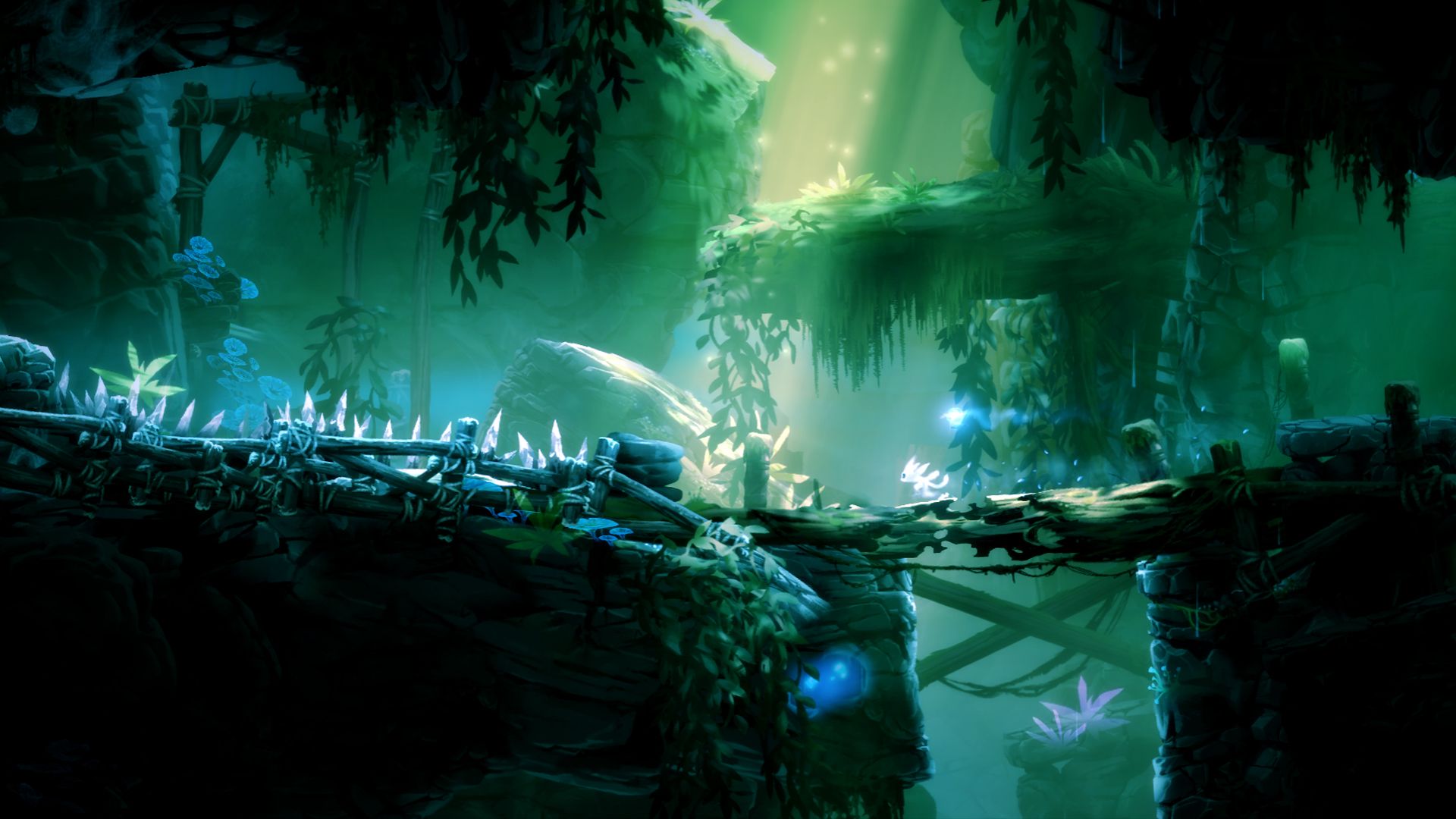

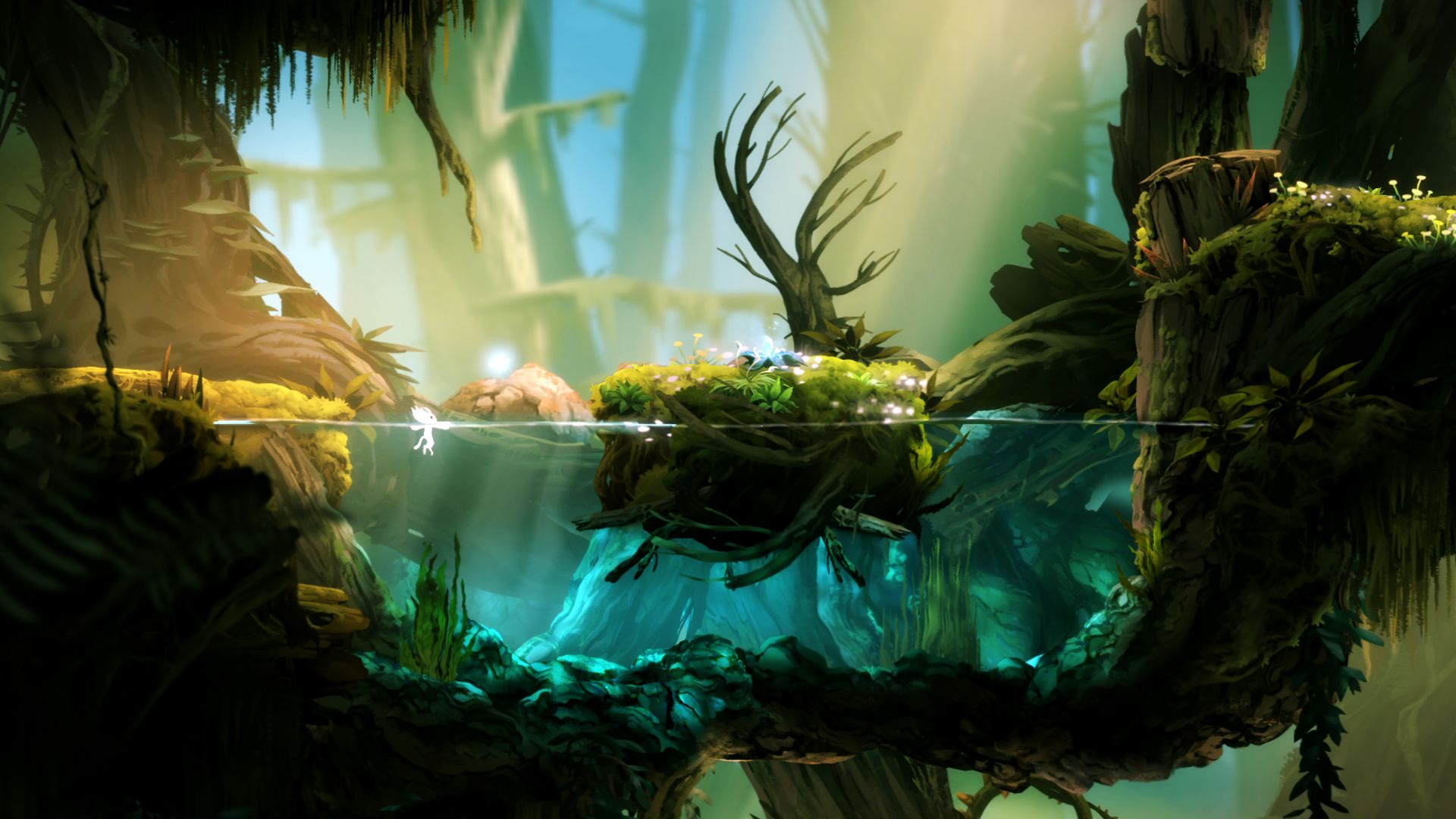

You know how it is, right, reader? We’re not the sort to be easily swayed by pretty graphics, no sir. We’re immune to the gaudy spectacles that assault us from above and below, from the hyper-realistic blood and sweat of the latest budget-breaking gun-car-man-athon all the way down to the eye-searing pixels of the latest obscure darling trying to draw on nostalgia that isn’t there. We’re here for substance, gameplay, storytelling and such, yes? Excellent, glad we’re on the same level. So, when the first thing I write about Ori and the Blind Forest is “every inch of Ori and the Blind Forest is absolutely drop-dead gorgeous”, I hope I’ve communicated the significance of putting that front-and-centre. Sure, you could divine that just from looking at the screenshots, but what the screenshots won’t tell you is how much of Ori and the Blind Forest is a painted diorama in constant, restless motion. It’s like the god of parallax scrolling reached down, and with a single divine thunderbolt, shattered the game into a thousand layers of artwork, all brought to life by the kind of subtle animation that you never consciously notice but nevertheless contributes to creating a breathing, natural environment. Branches sway, leaves tumble, water drips, ripples radiate away into the background. Does it look better than whatever people think is the glossiest new engine right now? No, probably not, but it made me stop and wonder “how on Earth did they do that?” numerous times, and that’s so much more remarkable.

Of course, there’s something of an unspoken expectation, when dealing with indie games, for the game’s propensity for beautiful artwork and soulful music to exist in an inverse relationship with how much of it could be actually referred to as ‘gameplay’ with a straight face, as if the mere act of touching the keyboard scatters that carefully constructed contemplative tone like a swarm of bees from a flamethrower. Sure, there might be some light platforming, maybe a puzzle or two, likely a scavenger hunt, but by and large you’re there more for the ever-so tragic moment at the end where a cute animal dies or something. Ori and the Blind Forest gets that out of its system as fast as reasonably possible. The game throws Ori – that’s you, the wispy Ghibli-esque creature that looks like an early piece of Mew concept art – into a murky pit, and yells “psyche! You’re in a Metroidvania!” It’s like the way Spec Ops: The Line completely subverts its mindless military shooter presentation about five minutes in, except you’re greeted with a genuinely pleasant surprise instead of the overwhelming urge to sit in an empty room and stare blank-eyed at the walls.

So what, right? Metroidvanias aren’t automatically perfect – except Super Metroid and Metroid Prime and Symphony of the Night and maybe a few others I can’t think of right now – and you can’t expect to slap a label like that on the table and hope it’s enough. Fortunately, Ori and the Blind Forest wastes no time in making sure you know that it means business: it is, in a word, genuinely brutal. Starting off, you’re a mewling helpless fuzz-ball with all the resilience of a stuffed animal, barely able to take a handful of hits before being vaporised and mortally threatened by every encounter you come across. I’ll readily admit that it’s a bit disconcerting for a game that looks like it’s one second away from unleashing a ‘Bambi’s mum dies’ moment to be so bloodthirsty right off the bat, but therein lies its strength: when you’re this fragile, you’ll travel to the ends of the Earth for a chance to boost your maximum health. So many Metroidvanias lack a sense of growth as a character because you’re basically just adding a few extra lines to a health bar that was already more than sufficient; Ori and the Blind Forest reminds us that it’s infinitely more satisfying to look back from the end-game, where you’re capable of slinging your way through incredibly hostile terrain with ease, and remember how you once pathetically skittered down the side of a tree like a cat on a waterslide.

Not that any of that does anything to help against the instant kill hazards, which are both strangely numerous and sometimes rather badly telegraphed. For the most part, the game’s visual clarity is excellent, which is pretty remarkable given the detail in each scene, but every now and then I found myself going from ‘intrepid traveller’ to ‘fantasy road-kill’ at the drop of a hat – or, to be more accurate, at the drop of a giant, seemingly innocuous slab of granite. In Super Metroid, where hours could easily pass between save points, it would’ve been a game-breaker; here, with Ori and the Blind Forest’s save system, it’s just kind of annoying. You’re essentially given a resource-limited quick-save: save anywhere, any time, so long as you’ve collected the necessary energy and you’re not standing in any immediate danger. Not an unheard-of idea, but energy is so plentiful and has so few other uses that you might as well save whenever you come up against anything more threatening than a rotting log, giving the game the instant-restart feel of a masocore platformer minus the ‘maso-‘. At times I felt like the game was looking over my shoulder, whispering “save scum” in my ear. I stand perched on the edge of a nasty-looking platforming challenge with more spikes than a crummy Mario rom-hack, my finger poised over the button. “Save scum,” the game repeats. “It’ll be so easy.” In the end I do, because I can’t remember when I last saved, and I don’t want a single mistake to undo my progress. Who wouldn’t?

That’s not to say there’s anything particularly wrong with the mechanics of the platforming itself. Ori’s movement is every bit as fluid as it looks – which is to say, like being in some kind of parkour-themed shampoo commercial – and the controls hold a near-perfect balance between responsiveness and momentum. Wall-jumping is relatively painless, something that we probably ought to be grateful for given how badly some games seem to bugger it up, and there’s even an ability later on that lets you use enemies and projectiles as spring-boards, with predictably radical results. I’ve been subjected to a chorus of moans to the general gist of “it’s too hard” for almost a week now, and sure, it can be fairly unforgiving, but have you guys played any indie platformers lately? Have you any idea what it’s like down here in Steam’s ‘upcoming’ tab, wading knee-deep through pixels as big as your clenched fist? Frankly, you’re getting off lightly.

Platforming in a side-scrolling Metroidvania, though, is like the skewer in a kebab: instrumental in maintaining the structure as a whole, but you’d feel deeply uncomfortable sitting opposite somebody who started savouring it over the rest of the experience. As always, we’re here to don our pith helmets and go exploring, and the game is pretty good at that if nothing else. I’m a little iffy on the whole business of finding hidden areas, since the hand-painted style means that discerning a solid wall from a non-solid wall is like trying to find a plastic fern in the middle of Kew Gardens, but the world is so big and varied and full of glowing things to collect that it hardly matters – and by the time it does, you can probably afford the X-ray upgrade anyway. You can find ability orbs, which contribute to your experience bar, health orbs, which ought to be self-explanatory if you’ve played a video game before, and energy orbs, which… uh… let you save and fire your charged attack more often, and therefore don’t matter. In accordance with the Video Game Developer Illuminati Guidelines (V1.4.152), Ori and the Blind Forest also incorporates RPG elements that manifest themselves when you collect enough ability orbs, allowing you to put points into a skill tree – though calling it a ‘tree’ might be giving too much credit to what is essentially three linear upgrade paths. Wasting ability points on stuff you don’t really want has always been a necessary evil of skill trees, but when your options are ‘upgrade this path’ and ‘don’t upgrade this path’, one wonders why the game bothers to offer you freedom of choice at all, especially when all three paths are equally appealing. The fact that enemies also drop small ability orbs means that you could probably cheat the system and grind your way through the skill tree instead of exploring, but honestly, why on Earth would anybody subject themselves to such a thing?

I suppose if I had any complaints to level at Ori and the Blind Forest, it’s that it’s a lot more conventional than it’d like you to think it is. The threat of generic ‘corruption’, manifesting as all-consuming gooey stuff that turns idyllic countryside into a slimy horrible nightmare land, is the fantasy equivalent of a horde of zombies: mindless, amoral, stock enemies to be slaughtered en-masse, requiring only the most paper-thin back-story to justify their existence to the world and possessing no face or character besides that of the main villain. There’s something very Zelda-y about the whole thing, even disregarding the amorphous enemies: the three magical artefacts, the three temples that are responsible for improving your situation in some utterly forgettable way, the fluttery fairy companion who never states anything meaningful, of course; and the dungeons that essentially function as an introduction, lecture, test and final exam for major new mechanics. You could see that as a good thing, and indeed most people probably will, but for a game with enough backing to achieve some really wild, ambitious ideas, Ori plays things pretty safely. Take away its extremely fetching exterior and it’s still a really good Metroidvania, but not one willing to break particularly new ground.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the storytelling. After the introductory segment you’d think that the game is setting up for some kind of poignant, heartstring-tugging adventure where you learn to survive being suddenly orphaned in an oppressive, dangerous, unfamiliar forest, but that all falls to the wayside and gets more or less forgotten with alarming brevity while you go off on a jaunt to save the world – yeah, again – at the behest of the Great Deku Tree’s spotty cousin. Heck, I’m not saying that I’d have preferred the former option, but when the game does try to elicit a reaction with a touching moment it feels so token and at-odds with everything else. There are some seriously impressive scripted sequences, mind, and the game is actually somewhat effective at making you empathise with characters who get less attention than Odessa Cubbage did, but none of them really relate to what’s actually going on until towards the very end, where it turns out that the big villain is just misunderstood and everything is saved by the power of love. It’s like the game started off with a simple, 16-bit-era plot, as befits a big open world with only a loosely-defined path through it, but then somebody looked at the beautiful art and decided that some kind of minimum ‘feelings’ quota needed to be filled.

There was only one thing I was interested in filling out, though, and that was the empty slots on the status screen. Ori and the Blind Forest had me in its clutches enough to warrant shooting for 100%, and it’s thanks to this final stretch that I discovered two massive hypodermic issues hiding in the innocuous brush: first, there are some areas that are sealed off once their story purpose is complete, so if you want the pick-ups inside them you need to get them on your first try; and second, not everywhere is sealed off as effectively as the game’s developers probably intended. It’s through these events that I found myself trapped between a rock and a broken scripted sequence, unable to escape or progress until I caved, downloaded a sketchy tool from the internet and started poking around with debugging menus I didn’t wholly understand. As far as solutions go it was a bit like performing open heart surgery by sticking your fingers in somebody’s chest cavity and wiggling them around a bit, but it nevertheless got the game back on its feet – albeit with a severe case of selective upgrade memory loss. It was a close call, and my perusal of the primordial slime pit that constitutes the Steam forums revealed that I was far from the only person to come up against game-breaking bugs. It’s a mite odd, too, because outside of a slightly dodgy physics object and some screen tearing on the map screen, the game hadn’t slipped an inch until then.

I’m going to warn you right now that even though Ori and Blind Forest is going to come sailing out of here with a nice, big, uncontested recommendation stapled to it, it’s not a game you ‘need’ to play. It’s not like The Stanley Parable or The Talos Principle, wherein I feel compelled to sell you on the game for your own good and the good of the medium at large; it’s just a really solid Metroidvania, clad in frankly stunning visuals. You could pass it by, and I won’t silently hold it against you. It won’t leave a legacy, or spawn imitators. In a world where games are constantly building on one another, it’s little more than a footnote, but that’s not the world where Ori seeks to have an effect. While those games may move us forward little by little, it’s the existence of games like this one that remind us why we move forward at all. It won’t be remembered for making any great contributions to gaming, but it might just be remembered in some minds, in a decade or so’s time, as that one game that turned one lazy Sunday into a beautiful, extraordinary, occasionally keyboard-snappingly difficult adventure. That’s just as important, right?